文章信息

- 梁洲瑞, 刘福利, 袁艳敏, 杜欣欣, 汪文俊, 孙修涛, 高亚平, 王飞久. 2018.

- LIANG Zhou-rui, LIU Fu-li, YUAN Yan-min, DU Xin-xin, WANG Wen-jun, SUN Xiu-tao, GAO Ya-ping, WANG Fei-jiu. 2018.

- 不同温度对极北海带幼苗生长及光合特性的影响

- Effect of different temperatures on growth and photosynthetic characteristic of Laminaria hyperborea young seedling

- 海洋科学, 42(4): 71-78

- Marine Sciences, 42(4): 71-78.

- http://dx.doi.org/10.11759/hykx20171121003

-

文章历史

- 收稿日期:2017-11-21

- 修回日期:2017-12-23

2. 青岛海洋科学与技术国家实验室, 海洋渔业科学与食物产出过程功能实验室, 山东 青岛 266000;

3. 上海海洋大学 水产与生命学院, 上海 201306;

4. 青岛农业大学 海洋科学与工程学院, 山东 青岛 266109

2. Laboratory for Marine Fisheries Science and Food Production Processes, Qingdao National Laboratory for Marine Science and Technology, Qingdao 266000, China;

3. College of Fisheries and Life Science, Shanghai Ocean University, Shanghai 201306, China;

4. College of Marine Science and Engineering, Qingdao Agricultural University, Qingdao 266109, China

极北海带(Laminaria hyperborea)属于褐藻纲(Phaeophyceae)、海带目(Laminariales)、海带科(Laminariaceae)、海带属(Laminaria), 其喜流水通畅、底质类型为岩礁的潮下带环境, 广泛分布于大西洋东北海域, 是形成“海藻森林”的优势种, 从葡萄牙至巴伦支海的沿岸, 包括英国、法罗群岛和冰岛的沿岸都有其分布[1-4]。据估计[5-6], 极北海带在挪威沿岸的分布面积达5 000~10 000 km2, 在3~5 m的水深范围内生物量达6~16 kg/m2。极北海带垂直分布上限是略高于最低天文潮位处, 下限有时达36 m, 在海水浑浊的环境中仅为1~2.5 m[2]。极北海带属多年生褐藻, 其平均寿命为8~15年, 在冰岛曾发现最大寿命为25年的极北海带[6-8]。极北海带个体较大, 藻体明显分为叶(呈掌状, 完整藻体一般分叉形成30片叶)、柄和固着器, 柄和叶的最大长度一般分别为1~3 m和1~2 m[2, 9-10]。

极北海带柄和叶片的褐藻胶含量分别为25%~ 30%和17%~33%(干质量比), 属于褐藻胶含量较高的种类[11], 其褐藻胶凝胶强度明显较大, 这与其古罗糖醛酸(Guluronic acid, G)含量较高有关(G含量在柄和叶片中分别占68%~70%和44%~55%)[11-12]。因此, 极北海带有重要的褐藻胶工业价值[13], 挪威每年对其采收量达13万~18万吨(鲜质量)[14]。目前, 挪威已开展了极北海带的人工养殖研究[15-16]。另外, 极北海带也具有生态价值, 是海洋生物的索饵场、产卵场或栖息地, 对维护海洋生物多样性发挥重要作用[17]。由于极北海带含有多种矿物元素、维生素等, 也可用于制作饲料添加剂及生物肥料[18-19]。温度、光照等因子对大型海藻的生长发育有影响[20-23]。极北海带幼苗对温度的耐受、光照的适应特征是决定其种苗成活的关键[24]。有人研究了不同季节极北海带叶片的固碳、呼吸和饱和光强等特征[25-28]。Kain等[29]研究了极北海带游动孢子在不同温度下的特征, 对比了配子体在不同温度下的生长速率及发育特点; Bolton等[30]也分析了极北海带配子体对高温的耐受程度。Kain等[24]报道了极北海带幼苗在不同温度下的生长速率和细胞分裂特征。但对于极北海带幼苗的温度耐受性及光照适应性(如光补偿点和饱和光强等光合参数), 尚未见报道。

本研究以极北海带配子体克隆技术培育的幼苗为对象, 研究不同温度条件下, 其幼苗生长及光合特征, 探讨温度对其幼苗早期生长发育的影响, 为极北海带苗种繁育及人工增养殖提供依据。

1 材料和方法 1.1 材料实验所用极北海带幼苗是通过配子体克隆技术培育获得, 极北海带配子体采集于法国布列塔尼半岛海区。幼苗培养条件为:温度11~13℃, 光合有效照射度(Photosynthetically Active Radiation, PAR)为40~50 μmol/(m2·s), 光周期12L︰12D, 天然海水经过滤、高压灭菌冷却后, 作为培养液, 添加营养盐(PO43–-P: 0.4 mg/L, NO3–-N: 4 mg/L)。选取1~15 cm幼苗作为实验材料。

1.2 方法使用液相氧电极(Hansatech Oxygraph, 英国)法测定表观光合速率与呼吸速率, 反应体系温度由恒温箱(Julabo, 德国)控制, 反应介质为灭菌天然海水, 以空气饱和的蒸馏水标定液相氧电极的满刻度, 通过加入少量保险粉(Na2S2O4·2H2O)标定零刻度。叶绿素荧光参数Fv/Fm(光系统Ⅱ最大荧光产量)的测定采用水下饱和脉冲叶绿素荧光仪DIVING-PAM(德国WALZ公司), 测定时需对幼苗先进行暗适应20 min。以下各个处理组均添加相同浓度的氮/磷营养盐(PO43–-P: 0.4 mg/L, NO3–-N: 4 mg/L)。以下每个测量实验重复3次。

1.2.1 不同温度下极北海带幼苗的相对生长速率的测定挑选2~4 cm的极北海带幼苗置于GXZ智能型光照培养箱, 进行2组测定相对生长速率的实验: (1)在PAR为60 μmol/(m2·s)的条件下, 分别在6、9、12、15、18、21、22和24℃下持续培养7 d。(2)在PAR为20 μmol/(m2·s)的条件下, 分别在5、9、13、17和21℃下持续培养7 d。实验开始前挑选藻体完整、无损伤腐烂的极北海带幼苗, 各处理组平均鲜质量为0.55 g±0.03 g, 鲜质量差异性不显著(P > 0.05)。每隔2 d换水一次, 7 d后称量一次鲜质量, 计算相对生长速率(RRG, relative growth rate), 计算公式如下: RRG= [ln(Wt/W0)/t]×100%, 其中W0为初始藻的鲜质量(g), Wt为实验结束时藻的鲜质量(g), t为实验持续的时间(d)。

1.2.2 极北海带幼苗在不同温度下处理后的光系统Ⅱ最大荧光产量Fv/Fm的测定温度梯度设置为6、9、12、15、18和21℃, PAR为50 μmol/(m2·s), 进行3组测定Fv/Fm的实验: (1)随机挑选藻体完整、无损伤、叶片长度为3~9 cm的极北海带幼苗60株, 以2~6株幼苗为一组(总质量为1.5 g±0.3 g), 放于盛有2 L培养液的三角烧瓶中, 测定在各个温度下处理1 h(包括暗适应的20 min)后幼苗的Fv/Fm。(2)挑选叶片长度为1~3 cm、5~7 cm和9~11 cm的幼苗各30株, 按上述方法测定其Fv/Fm。(3)测定在21℃下进行胁迫处理12 h和24 h后幼苗的Fv/Fm, 接着在12℃下进行恢复培养24 h和48 h后, 再分别测定其Fv/Fm。

1.2.3 不同温度下极北海带幼苗的表观光合速率和呼吸速率的测定在5、9、13和17℃下测定极北海带幼苗的表观光合速率及呼吸速率。挑选长度为1.0 cm±0.2 cm的极北海带幼苗, 称0.020 g±0.002 g放进液相氧电极反应杯, 反应杯中添加2 mL培养液并控制在所设置的温度下, 以LED灯做光源, 通过移动光源距离调节PAR, 测定时将探头置于反应杯所在的中心位置, 正对光源读数。分别测出极北海带幼苗在0、10、20、40、60、80、90、100、110 μmol/(m2·s)等PAR下的表观光合速率, 先在低PAR下测量, 当测量PAR逐渐增大直至使幼苗出现光抑制时, 再继续在2个更高PAR水平下进行表观光合速率的测量。每个PAR下需稳定10 min左右再测量, 每次测定在10 min之内完成, 取较为平滑曲线计算光合/呼吸速率。每变换1次PAR测定前, 先更换1 mL新的培养液, 以减少因反应杯中培养液的氮磷消耗而产生的误差。另外, 挑选长度为13 cm±2 cm的幼苗, 在其中间部位剪下一片质量为0.020 g±0.002 g的叶片, 用上述同样方法, 在13℃和17℃下测定幼苗的表观光合速率及呼吸速率。剪下的小叶片需在培养液中放置1 h后再进行测量, 以减小藻体损伤对光合和呼吸作用所造成的影响。

1.3 数据处理采用SPSS 19.0数据统计软件进行方差分析、多重比较, 以P < 0.05作为显著性差异, 用Excel软件绘制图形。利用叶子飘等机理模型[31]拟合极北海带幼苗的光合-光响应曲线, 求出其光合参数——最大表观光合速率(maximal net photosynthetic rate, Pnmax)、饱和光强(saturation irradiance, Isat)、光补偿点(light compensation point, Ic)、光响应曲线初始斜率α和暗呼吸速率(dark respiration rate, Rd)等。

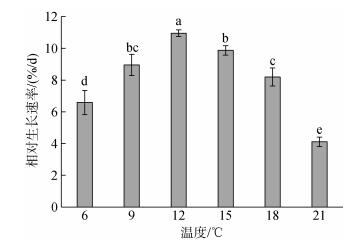

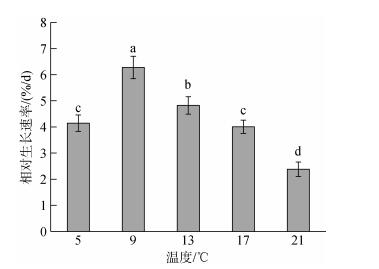

2 结果 2.1 不同温度下极北海带幼苗的相对生长速率由图 1看出, 在PAR为60 μmol/(m2·s)下, 12℃温度组的RRG最大, 其他温度处理组与其相比均呈显著性差异(P < 0.05), 该条件下RRG由大到小排序为: 12℃ > 15℃ > 9℃ > 18℃ > 6℃ > 21℃。由图 2看出, 在PAR为20 μmol/(m2·s)下, 9℃温度组的RRG最大, 其他温度处理组与其相比均呈显著性差异(P < 0.05), 该条件下RRG由大到小排序为: 9℃ > 13℃ > 5℃ > 17℃ > 21℃。另外, 幼苗在22℃下培养至第4天时就出现了严重的病烂现象, 如叶片颜色变淡、有多个白点或穿孔; 而在24℃下培养的幼苗在培养至第2天时就出现了上述病烂现象, 且培养3 d后叶片就全部腐烂分解。

|

| 图 1 PAR为60 μmol/(m2·s)下不同温度处理7 d后极北海带幼苗的相对生长速率 Fig. 1 The relative growth rates of L. hyperborea young seedlings treated with different temperatures for 7 days of cultivation at PAR of 60 μmol/(m2·s) 柱状图上的不同字母表示差异性显著, 下同 The different letters on the histogram show significant differences |

|

| 图 2 PAR为20 μmol/(m2·s)下, 不同温度处理7 d后极北海带幼苗的相对生长速率 Fig. 2 The relative growth rates of L. hyperborea young seedlings treated with different temperatures for 7 days of cultivation at PAR of 20 μmol/(m2·s) |

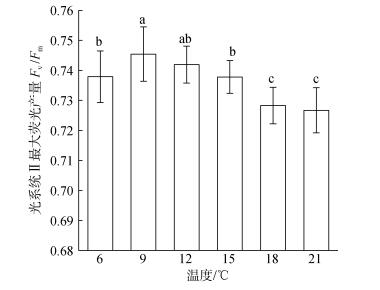

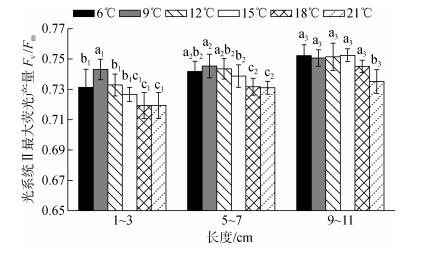

方差分析结果表明, 温度及叶片长度对极北海带幼苗的Fv/Fm均有显著影响(P < 0.05), 见图 3和图 4。9℃和12℃处理组的幼苗的Fv/Fm较高, 该两组之间相比无显著性差异(P > 0.05), 而18℃和21℃的高温处理组的幼苗在处理1 h后的Fv/Fm均较低, 与其他处理组相比均呈显著性差异(P < 0.05), 见图 3。如图 4所示, 同一温度下, 幼苗长度越长, Fv/Fm越高。对于1~3 cm长度组, 9℃下的幼苗Fv/Fm最大, 其他温度处理组与其相比呈显著性差异(P < 0.05), 在9~21℃范围内的幼苗Fv/Fm随着温度的升高呈现明显逐渐下降的趋势。对于5~7 cm长度组, 18℃和21℃处理组与其他组相比均呈显著性差异(P < 0.05)。对于9~11 cm长度组, 6~18℃范围内, 各处理组之间相比无显著性差异(P > 0.05)。

|

| 图 3 极北海带幼苗(长3~9 cm)在不同温度下处理1 h后的Fv/Fm Fig. 3 Fv/Fm of L. hyperborea young seedlings with the length of 3~9 cm at different temperatures for 1 h respectively |

|

| 图 4 不同叶片长度的极北海带幼苗在不同温度下处理1 h后的Fv/Fm Fig. 4 Fv/Fm of L. hyperborea young seedlings with different length at different temperatures for 1 h respectively 柱状图上的字母下标为相同数字的作为同一组进行多重比较, 同一组的不同字母表示差异性显著, 下同 Marked as the same number on a histogram. The letters in the same group are compared. The different letters in the same group represent significant differences, and the following are the same |

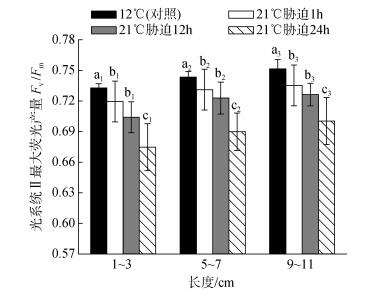

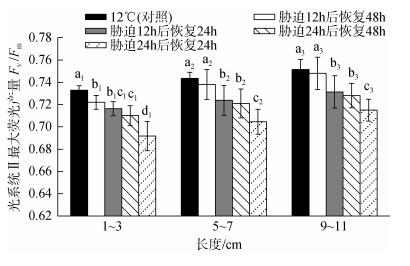

方差分析结果表明, 21℃胁迫时间的长短对不同长度的极北海带幼苗的Fv/Fm均有显著影响(P < 0.05)。如图 5所示, 在相同的胁迫处理时间下, 幼苗长度越长, Fv/Fm越高。对于同一长度组, Fv/Fm的变化趋势相同, 即随着21℃胁迫处理时间的增加, 幼苗的Fv/Fm逐渐降低, 且Fv/Fm在胁迫处理1 h后就与对照组(12℃)的相比呈显著性差异(P < 0.05); 21℃胁迫1 h和胁迫12 h的处理组之间相比无显著性差异(P > 0.05), 而这两者与胁迫24 h的处理组之间相比均呈显著性差异(P < 0.05)。如图 6所示, 对于5~7 cm和9~11 cm长度组, 21℃胁迫12 h处理组的幼苗在恢复培养48 h后的Fv/Fm与12℃组的相比均无显著性差异(P > 0.05), 表明其已恢复至正常水平。而胁迫24 h处理组的Fv/Fm在恢复培养24 h和48 h后均无法恢复到正常水平, 与12℃组的相比呈显著性差异(P < 0.05)。

|

| 图 5 不同长度的极北海带幼苗在21℃下处理1、12和24 h后的Fv/Fm Fig. 5 Fv/Fm of L. hyperborea young seedlings with different length at 21℃ for 1 h, 12 h and 24 h respectively |

|

| 图 6 不同长度的极北海带幼苗在21℃下胁迫处理12 h和24 h后分别恢复培养24 h和48 h后的Fv/Fm Fig. 6 Fv/Fm of L. hyperborea young seedlings with different length at 21℃ for 12 h and 24 h respectively and the recovery values after 24 h and 48 h |

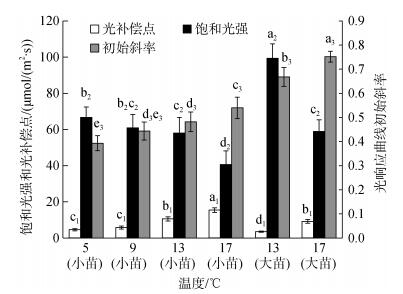

由图 7看出, 对于同一长度的极北海带幼苗, 在5~17℃范围内, 随着温度的升高, 幼苗的光补偿点(Ic)和饱和光强(Isat)均呈逐渐升高的趋势, 而光响应曲线初始斜率α则呈逐渐降低的趋势。同一温度(13℃和17℃)下, 对于Ic, 长度为13 cm±2 cm的极北海带“大苗”均显著(P < 0.05)小于长度为1.0 cm±0.2 cm的“小苗”, 而对于Isat和α, “大苗”均显著(P < 0.05)大于“小苗”。5、9、13和17℃下, 长度为1.0 cm±0.2 cm的幼苗Ic分别为4.6、5.8、10.6、15.4 μmol/(m2·s), Isat分别为52.4、59.1、64.2、71.9 μmol/(m2·s)。13℃和17℃下, 长度为13 cm±2 cm的幼苗Ic分别为3.5和9.2 μmol/(m2·s), Isat分别为89.1和100.3 μmol/(m2·s)。

|

| 图 7 不同温度下极北海带幼苗的光补偿点、光响应曲线初始斜率和饱和光强 Fig. 7 The light compensation point, the initial slope of light response curve and saturation irradiance of L. hyperborea at different temperatures 小苗长度. 1.0 cm±0.2 cm; 大苗长度. 13 cm±2 cm Small Seedling length. 1.0 cm±0.2 cm; Big seedling length. 13 cm±2 cm |

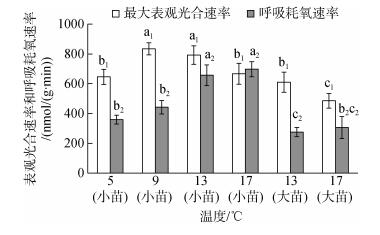

由图 8看出, 9℃和13℃组中长度为1.0 cm±0.2 cm的极北海带“小苗”的最大表观光合速率(Pnmax)较大, 与其他温度组的相比均呈显著性差异(P < 0.05), 9℃组“小苗”的Pnmax次之。对于同一长度的极北海带幼苗, 在5~17℃范围内, 随着温度的升高, 幼苗的呼吸速率(Rd)呈逐渐升高的趋势。同一温度(13℃和17℃)下, 长度为13 cm±2 cm的“大苗”的Pnmax和Rd均显著小于“小苗”(P < 0.05)。

|

| 图 8 不同温度下极北海带幼苗的最大表观光合速率和呼吸耗氧速率 Fig. 8 The maximal net photosynthetic rates and dark respiration rates of L. hyperborea at different temperatures 小苗长度. 1.0 cm±0.2 cm; 大苗长度. 13 cm±2 cm Small Seedling length. 1.0 cm±0.2 cm; Big seedling length. 13 cm±2 cm |

本研究的RRG结果显示, 低温组(5℃和6℃)和高温组(17~21℃)的极北海带幼苗RRG均较低, 9~15℃时RRG较高; 与RRG结果相对应的是, 低温(5℃)和高温(17℃)下极北海带幼苗的Pnmax均较低, 而9℃和13℃组的幼苗具有较大的Pnmax; 另外, Fv/Fm结果显示9~15℃范围内的Fv/Fm均较大。因此, 极北海带幼苗的适宜温度范围在9~15℃, 这与Kain等[24, 29]和Bolton[30]的结果大致相似。真海带(Saccharina japonica)[32-33]、掌状海带(L. digitata)[34]、长海带(S. longissima)[35]、利尻海带(S. ochotensis)[36]、糖海带(L. saccharina)[30]和巨藻(Macrocystis pyrifera)[37]等大型冷温性海藻幼苗的生长适宜温度多在10~15℃范围内, 但其最适温度、光照、营养盐等需求略有差别。

高温对冷温性大型海藻的生长和光合作用有较大影响[38-39]。极北海带幼苗在18℃和21℃下短时间(1 h)胁迫处理后Fv/Fm均显著降低, 表明幼苗易受高温胁迫。幼苗在21℃胁迫24 h并在适宜温度下分别恢复培养24 h和48 h后的Fv/Fm均无法恢复到正常水平, 表明21℃下培养使幼苗的光系统Ⅱ受到了不可逆的损伤。Kain等认为[24, 40], 高于17℃时极北海带配子体存活率显著下降, 少数配子体能在20℃下存活, 且当温度大于19℃时, 配子体不能转变为孢子体, 在实验室适宜的条件下, 极北海带幼苗(0.8~4 mm)可在20℃下常生长。Bolton等[30]研究表明, 极北海带配子体的生长限制温度为21℃, 5~8 cm的极北海带幼苗可在0~20℃下生长, 而不能在23℃下生长。而本研究中长度为2~4 cm的幼苗可在21℃下生长, 当温度≥22℃时, 2~4天后幼苗就开始病烂。据此, 21℃是极北海带幼苗室内培养的上限。

叶片长度对极北海带幼苗的Fv/Fm有显著影响, 同一温度下, 叶片越长则幼苗Fv/Fm越高, 由此推测较大的极北海带幼苗有着较高的光能转换效率。叶长较小组的Fv/Fm随着温度的升高呈现下降的趋势较明显, 表明较小的幼苗对温度的升高反应较敏感。在高温(21℃)胁迫处理时间一样的情况下, 叶片越长则幼苗的Fv/Fm越高, 且5~11 cm长度组在21℃胁迫12 h后再恢复培养48 h后的Fv/Fm可恢复至正常水平, 而1~3 cm长度组的不能恢复, 表明较大的极北海带幼苗相对耐受高温。本研究发现, 同一温度下, 长13 cm±2 cm的“大苗”的Pnmax和Rd均显著小于1.0 cm±0.2 cm的“小苗”, 这可能与叶龄或叶片的厚薄有关。

极北海带分布在潮下带, 其幼苗表现出较低的Ic和Isat。作者发现, 在5~17℃范围内, 极北海带幼苗(1~15 cm)Ic范围为4.6~15.4 μmol/(m2·s), Isat范围为52.4~100.3 μmol/(m2·s)。而长0.8~1 cm的海带(S. japonica)幼苗在10℃下的Ic为8~10 μmol/(m2·s), Isat约为200 μmol/(m2·s)[41-42]。据此推测, 极北海带相对海带更能耐受弱光, 但更易受到强光的伤害。因此, 极北海带幼苗在海上暂养时应当置于较低的水层。研究表明, 极北海带叶片在不同季节(水温)下会表现出不同的Ic和Isat[37]。作者发现, 极北海带幼苗的Ic和Isat随着温度的升高均呈逐渐升高的趋势, 而光响应曲线初始斜率α则呈逐渐降低的趋势。这表明在低温下, 极北海带幼苗可适应较弱的光照, 但其对强光的耐受性较低。大型藻类的Ic和Isat还因不同生长阶段而有所差异[43-44]。本研究发现, 同一温度下, 长13 cm±2 cm的极北海带“大苗”的Isat均显著大于长为1.0 cm±0.2 cm的“小苗”, 而对于Ic则相反, 这表明较大的极北海带幼苗更耐受强光, 且可适应更弱的光照。

| [1] |

Kain J M. Populations of Laminaria hyperborea at various latitudes[J]. Helgolnder Wissenschaftliche Meeresuntersuchungen, 1967, 15(1-4): 489-499. DOI:10.1007/BF01618645 |

| [2] |

Kain J M. Synopsis of biological data on Laminaria hyperborea[M]. FAO: Fisheries Synopsis No. 87, 1971.

|

| [3] |

Kain J M, Jones N S. The biology of, Laminaria hyperborea Ⅵ. some norwegian populations[J]. Journal of the Marine Biological Association of the United Kingdom, 1971, 51(2): 387-408. DOI:10.1017/S0025315400031866 |

| [4] |

Schoschina E V. On Laminaria hyperborea (Laminariales, phaeophyceae) on the murman coast of the barents sea[J]. Sarsia North Atlantic Marine Science, 1997, 82(4): 371-373. |

| [5] |

Christie H, J rgensen N M, Norderhaug K M, et al. Species distribution and habitat exploitation of fauna associated with kelp (Laminaria hyperborea) along the Norwegian Coast[J]. Journal of the Marine Biological Association of the Uk, 2003, 83(4): 687-699. DOI:10.1017/S0025315403007653h |

| [6] |

Gunnarson K. Populations de Laminaria hyperborea et Laminaria digitata (Pheophycees) dans la Baie de Breidifjrdur, Islande[J]. Rit Fiskideildar, 1991, 12: 1-148. |

| [7] |

Sj tun K, Fredriksen S, Lein T E, et al. Population studies of Laminaria hyperborea from its northern range of distribution in Norway[J]. Proceedings of the International Seaweed Symposium, 1993, 14: 215-221. |

| [8] |

Kelly E. The role of kelp in the marine environment[J]. Irish Wildlife Mannuals, 2005, 17: 1393-1399. |

| [9] |

Kain J M. Aspects of the biology of Laminaria hyperborea Ⅰ. vertical distribution[J]. Journal of the Marine Biological Association of the United Kingdom, 1962, 42(2): 377-385. DOI:10.1017/S0025315400001363 |

| [10] |

Jupp B P, Drew E A. Studies on the growth of Laminaria hyperborea, (Gunn.) Fosl. Ⅰ. Biomass and productivity[J]. Journal of Experimental Marine Biology & Ecology, 1974, 15(2): 185-196. |

| [11] |

Qin Y. Alginate fibres: an overview of the production processes and applications in wound management[J]. Polymer International, 2008, 57(2): 171-180. DOI:10.1002/(ISSN)1097-0126 |

| [12] |

Draget K I, Phillips G O, Williams P A. Handbook of Hydrocolloids[M].2009: 807-828. doi: 10.1533/9781845695873.807.

|

| [13] |

Bixler H J, Porse H. A decade of change in the seaweed hydrocolloids industry[J]. Journal of Applied Phycology, 2011, 23(3): 321-335. DOI:10.1007/s10811-010-9529-3 |

| [14] |

Vea J, Ask E. Creating a sustainable commercial harvest of Laminaria hyperborea, in Norway[J]. Journal of Applied Phycology, 2011, 23(3): 489-494. DOI:10.1007/s10811-010-9610-y |

| [15] |

Stévant P, Rebours C, Chapman A. Seaweed aquaculture in Norway: recent industrial developments and future perspectives[J]. Aquaculture International, 2017(12): 1-18. |

| [16] |

Skjermo J, Aasen I M, Arff J, et al. A new Norwegian bioeconomy based on cultivation and processing of seaweeds: Opportunities and R & D needs[R]. SINTEF Fisheries and Aquaculture, 2014: 1-46.

|

| [17] |

Dan A S, Burrows M T, Moore P, et al. Threats and knowledge gaps for ecosystem services provided by kelp forests: a northeast Atlantic perspective[J]. Ecology & Evolution, 2013, 3(11): 4016-4038. |

| [18] |

范晓. 海藻作为饲料添加剂的研究和利用[J]. 饲料工业, 1991(11): 14-16. Fan Xiao. Research and utilization of algae as feed additives[J]. Feed Industry, 1991(11): 14-16. |

| [19] |

Schiener P, Black K D, Stanley M S, et al. The seasonal variation in the chemical composition of the kelp species Laminaria digitata, Laminaria hyperborea, Saccharina latissima, and Alaria esculenta[J]. Journal of Applied Phycology, 2015, 27(1): 363-373. DOI:10.1007/s10811-014-0327-1 |

| [20] |

Major K M, Davison I R. Influence of temperature and light on growth and photosynthetic physiology of Fucus evanescens (Phaeophyta) embryos[J]. European Journal of Phycology, 1998, 33(2): 129-138. DOI:10.1080/09670269810001736623 |

| [21] |

Wiencke C, Gómez I, Pakker H, et al. Impact of UV- radiation on viabillitay, photosynthetic characteristics and DNA of brown algal zoospores: imlications for depth zonation[J]. Nuclear Instruments & Methods in Physics Research, 2000, 147(1-4): 29-34. |

| [22] |

Coelho S, Rijstenbil J W, Sousa-Pinto I, et al. Cellular responses to elevated light levels in Fucus spiralis embryos during the first days after fertilization[J]. Plant Cell & Environment, 2001, 24(8): 801-810. |

| [23] |

邓璐, 曹翠翠, 王宏伟. 温度、光照强度和盐度对海柏果孢子放散与附着的影响[J]. 海洋科学, 2015, 39(8): 24-27. Deng Lu, Cao Cuicui, Wang Hongwei. Influence of temperature, light intensity and salinity on carpospores releasing and attachment of Polyopes polyideoides (Halymeniaceae, Rhodophyta)[J]. Marine Sciences, 2015, 39(8): 24-27. |

| [24] |

Kain J M, Jones M N S. Aspects of the biology of Laminarja hyperborea Ⅳ. Growth of early sporophytes[J]. Journal of the Marine Biological Association of the United Kingdom, 1965, 45(1): 129-143. DOI:10.1017/S0025315400004033 |

| [25] |

Lüning K. Seasonal growth of Laminaria hyperborea under recorded underwater light conditions near Helgoland[C]// Crisp D J. Proceedings of the Fourth European Marine Biology Symposium. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1971: 347-361.

|

| [26] |

Kremer B P. Carbohydrate reserve and dark carbon fixation in the brown macroalga, Laminaria hyperborea[J]. Journal of Plant Physiology, 1984, 117(3): 233-242. DOI:10.1016/S0176-1617(84)80005-X |

| [27] |

Willenbrink J, Rangonikübbeler M, Tersky B. Frond development and CO2-fixation in Laminaria hyperborea[J]. Planta, 1975, 125(2): 161-170. |

| [28] |

Drew E A, Jupp B P, Robertson W A A. Photosynthesis and growth of Laminaria hyperborea in British Waters[J]. Underwater Research, 1976, 369-379. |

| [29] |

Kain J M, Jones N S. Aspects of the biology of Laminaria hyperborea Ⅲ. Survival and growth of gametophytes[J]. Journal of the Marine Biological Association of the United Kingdom, 1964, 44(2): 415-433. DOI:10.1017/S0025315400024929 |

| [30] |

Bolton J J, Lüning K. Optimal growth and maximal survival temperatures of Atlantic Laminaria, species (Phaeophyta) in culture[J]. Marine Biology, 1982, 66(1): 89-94. DOI:10.1007/BF00397259 |

| [31] |

Ye Z P, Suggett D J, Robakowski P, et al. A mechanistic model for the photosynthesis-light response based on the photosynthetic electron transport of photosystem Ⅱ in C3 and C4 species[J]. New Phytologist, 2013, 199(1): 110-120. DOI:10.1111/nph.12242 |

| [32] |

姚海芹, 梁洲瑞, 刘福利, 等. 利用液相氧电极技术研究"海天1号"海带(Saccharina japonica)幼孢子体光合及呼吸速率[J]. 渔业科学进展, 2016, 37(1): 140-147. Yao Haiqin, Liang Zhourui, Liu Fuli, et al. Preliminary studies on the photosynthetic and respiration rate of young sporophyte of a new Saccharina variety "Haitian No. 1" using liquid-phase oxygen measurement system[J]. Marine Fisheries Research, 2016, 37(1): 140-147. |

| [33] |

曾呈奎, 吴超元, 孙国玉. 温度对海带孢子体的生长和发育的影响[J]. 植物学报, 1957, 6(2): 103-130. Zeng Chengkui, Wu Chaoyuan, Sun Guoyu. The effect of temperature on the growth and development of Laminaria japonica sporophyte[J]. Acta Botanica Sinica, 1957, 6(2): 103-130. |

| [34] |

凌晶宇, 梁洲瑞, 王飞久, 等. 温度胁迫对掌状海带幼苗生长、抗氧化系统及叶绿素荧光的影响[J]. 海洋科学, 2015, 39(12): 39-45. Ling Jingyu, Liang Zhourui, Wang Feijiu, et al. Effects of temperature stress on the growth, antioxidant system, and chlorophyll fluorescence of Laminaria digitata[J]. Marine Sciences, 2015, 39(12): 39-45. DOI:10.11759/hykx20150107001 |

| [35] |

张泽宇, 范春江, 曹淑青, 等. 长海带海区暂养与栽培技术的研究[J]. 大连海洋大学学报, 1999, 14(1): 16-21. Zhang Zeyu, Fan Chunjiang, Cao Shuqing, et al. Study on the indoor culture and cultivition of Laminaria longissima Mayabe[J]. Journal of Dalian Fisheries University, 1999, 14(1): 16-21. DOI:10.3969/j.issn.1000-9957.1999.01.003 |

| [36] |

张泽宇, 范春江, 曹淑青, 等. 利尻海带的室内培养与栽培的研究[J]. 大连海洋大学学报, 2000, 15(2): 103-107. Zhang Zeyu, Fan Chunjiang, Cao Shuqing, et al. Indoor culture and cultivation of Laminaria ochotensis[J]. Journal of Dalian Fisheries University, 2000, 15(2): 103-107. DOI:10.3969/j.issn.1000-9957.2000.02.005 |

| [37] |

凌晶宇, 梁洲瑞, 孙修涛, 等. 巨藻幼苗光合、呼吸作用的初步研究[J]. 水产学报, 2014, 38(6): 820-828. Ling Jingyu, Liang Zhourui, Sun Xiutao, et al. Primary investigations on the photosynthesis and respiration of Macrocystis pyrifera[J]. Journal of Fisheries of China, 2014, 38(6): 820-828. |

| [38] |

李德茂, 王广策, 李兆生, 等. 光照强度和温度对营养生长的巨藻雌、雄配子体光合放氧的影响[J]. 海洋科学, 2005, 29(12): 51-55. Li Demao, Wang Guangce, Li Zhaosheng, et al. The effects of light intensity and temperature on photosynthetic oxygen evolution of the female and male gametophytes of Macrocystis pyrifera[J]. Marine Sciences, 2005, 29(12): 51-55. DOI:10.3969/j.issn.1000-3096.2005.12.012 |

| [39] |

朱明远, 吴荣军, 李瑞香, 等. 温度对海带幼孢子体生长和光合作用的影响[J]. 生态学报, 2004, 24(1): 22-27. Zhu Mingyuan, Wu Rongjun, Li Ruixiang, et al. Effects of temperature on the growth and Photosynthesis of young sporophyte of Laminaria japonica[J]. Acta Ecologica Sinica, 2004, 24(1): 22-27. DOI:10.3321/j.issn:1000-0933.2004.01.004 |

| [40] |

Kain J M. Biology of Laminaria hyperborea V. comparison with early stages of competitors[J]. Journal of the Marine Biological Association of the United Kingdom, 1969, 49(2): 455-473. DOI:10.1017/S0025315400036031 |

| [41] |

岳国峰.海带配子体和幼孢子体无机碳素营养的比较研究[D].青岛: 中国科学院海洋研究所, 2000. Yue Guofeng. Comparative studies on inorganic carbon acquisition by gametophyte and juvenile sporophyte of Laminaria japonica[D]. Institute of Oceanology, Chinese Academy of Sciences, 2000. |

| [42] |

曾呈奎, 吴超元. 海带养殖学[M]. 北京: 科学出版社, 1962: 1-68. Zeng Chengkui, Wu Chaoyuan. Cultivation of Laminaria japonica[M]. Beijing: Science Press, 1962: 1-68. |

| [43] |

曾呈奎, 潘忠正, 周百成. 底栖海藻比较光合作用研究Ⅱ.潮间带褐藻的光合作用与光强的关系[J]. 海洋与湖沼, 1981, 12(3): 254-258. Zeng Chengkui, Pan Zhongzheng, Zhou Baicheng. Comparative photosynthetic studies on benthic seaweeds Ⅱ. The effect of light intensity on photosynthesis of intertidal brown algae[J]. Oceanologia et Limnologia Sinica, 1981, 12(3): 254-258. |

| [44] |

张栩, 李大鹏, 施定基, 等. 裙带菜配子体和幼孢子体的光合作用特性[J]. 海洋科学, 2004, 28(11): 20-27. Zhang Xu, Li Dapeng, Shi Dingji, et al. Photosynthesis properties of gametophytes and juvenile sporophytes of algae, Undaria pinnatifida[J]. Marine Sciences, 2004, 28(11): 20-27. DOI:10.3969/j.issn.1000-3096.2004.11.006 |

2018, Vol. 42

2018, Vol. 42