文章信息

- 王兆瑞, 杨小彤, 孙敬锋, 王江勇. 2023.

- WANG Zhao-rui, YANG Xiao-tong, SUN Jing-feng, WANG Jiang-yong. 2023.

- 几种物理因素对北海派琴虫体外培养方法优化的影响

- Effect of physical factors on optimizing in vitro culture of Perkinsus beihaiensis

- 海洋科学, 47(3): 57-65

- Marine Sciences, 47(3): 57-65.

- http://dx.doi.org/10.11759/hykx20210722001

-

文章历史

- 收稿日期:2021-07-22

- 修回日期:2022-01-25

2. 中国水产科学研究院 南海水产研究所 广东省渔业生态环境重点实验室, 广东 广州 510300;

3. 天津农学院, 天津 300384

2. Key Lab of Fishery Ecology and Environment, Key Lab of South China Sea Fishery Resources Exploitation & Utilization, Ministry of Agriculture, Guangzhou 510300, China;

3. Tianjin Agricultural University, Tianjin 300384, China

派琴虫的宿主主要是软体双壳类动物[1], 被派琴虫感染后的宿主生长缓慢、生殖量减少, 宿主组织萎缩或溶解, 通常在宿主达到生殖成熟后死亡[2]。19世纪60年代, 派琴虫因引起美国墨西哥海湾牡蛎大规模死亡而被发现[3-5]。至今, 在全球范围内都曾发生过因派琴虫感染而使养殖贝类大规模死亡的案例[6-7]。派琴虫已然成为一种世界性的贝类寄生虫感染病, 是贝类养殖过程中不可忽略的病原微生物。从派琴虫被发现至今, 已发现7种被认可的种, 分别是海洋派琴虫(Perkinsus marinus), 奥尔森派琴虫(Perkinsus olseni), 库瓦迪派琴虫(Perkinsus qugwadi), 切萨皮克派琴虫(Perkinsus cheasapeaki), 地中海派琴虫(Perkinsus mediterraneus), 本州派琴虫(Perkinsus honshuensis), 和北海派琴虫(Perkinsus beihainensis)[8], 其中P. beihainensis是在中国北海发现的[9]。因为在所有的派琴虫种中P. marinus和P. olseni是致病性最强的, 所以将所有派琴虫引起的疾病统称为奥尔森派琴虫病。

派琴虫的生活史主要分4个阶段: 滋养体、休眠孢子、游动孢子囊、游动孢子[10]。其中滋养体是宿主体内寄生的主要营养增殖阶段, 此阶段派琴虫细胞具有明显的印戒结构, 会在宿主体内引起炎症, 是致病的主要毒力阶段[11]。休眠孢子阶段是派琴虫体为了抵抗外界不良的生活条件而对外界做出的应激反应, 在此阶段下, 其细胞壁不断增厚, 这一阶段在RFTM培养后, 已得到证实[12]。当休眠孢子被置于营养培养基中后, 会通过核分裂和胞质分裂形成游动孢子囊, 最终游动孢子囊通过其细胞壁上的释放孔将游动孢子释放到外界[13]。当游动孢子被释放后会逐渐失去游动孢子的特性, 如鞭毛和体型, 转变为静止的滋养体[14], 随后发育成裂殖体, 并最终释放出多个子细胞, 称为裂殖子[15]。

传统的派琴虫培养方法是, 先通过雷氏巯基乙酸盐培养基(RFTM)将派琴虫的休眠期孢子培养增大[16], 然后通过动物细胞培养基(DME/F-12)进行分裂增殖培养[17]。完成这个增殖过程一般需要20 d左右, 这要比培养一般的细胞或细菌等微生物周期长得多。过长的培养周期在一定程度上阻碍了派琴虫感染等下游研究的开展, 因此探究缩短派琴虫培养时间的研究就具有重要的现实意义。本实验旨在模仿派琴虫在大自然中的环境, 通过单一或协同改变盐度、温度、震荡条件这3个主要的物理因子, 来确定刺激派琴虫生长的最优物理因子组合, 以期达到派琴虫体快速扩增的目的, 为派琴虫的下游实验的开展提供科学依据和方法。

1 材料和方法 1.1 实验材料及处理所用培养材料的菲律宾蛤仔为天然宿主, 取自广东省广州市海珠区水产市场, 壳长4.2~5.8 cm, 壳高1.3~3.6 cm。

无菌操作下取菲律宾蛤仔的鳃和外套膜匀浆, 取匀浆后的部分组织置于1.5 mL无菌离心管中, 用于派琴虫的检测。将剩余组织置于50 mL无菌离心管中待培养。

1.2 样品DNA提取使用DNA提取试剂盒(试剂盒购自广州美基生物科技有限公司)提取组织样品DNA。运用聚合酶链式反应(PCR)检测, 采用OIE派琴虫通用引物F-PerkITS-85(5′CCGCTTTGTTTGGATCCC3′)和R-PerkITS-750(5′ACATCAGGCCTTCTAATGATG 3′)[18]进行PCR扩增。PCR反应程序为40个循环: 预变性95 ℃, 4 min; 变性95 ℃, 1 min; 退火53 ℃, 1 min; 延伸72 ℃, 1 min。最后72 ℃延伸7 min。

1.3 派琴虫体外培养将被侵染组织样品放入抗生素浸液(青霉素400 000 U/L; 链霉素400 mg/L; 庆大霉素200 mg/L; 卡那霉素400 mg/L; 新霉素0.2 mg/L; 多粘菌素200 mg/L; 红霉素400 mg/L)中, 孵育半小时后, 间隔5 min, 再孵育半小时以去除组织中的其他微生物且让派琴虫细胞适应新环境(孵育时间过长会杀死派琴虫细胞)。孵育后的组织样品用无菌海水冲洗至少2次, 随后转入6孔培养板中, 每孔加入2.5 mL可替代的雷氏液体巯基乙酸盐(ARFTM)[19]培养基, 随后用锡箔纸完全包裹, 28 ℃避光培养48 h。培养箱中放入一个装入水的3 L大烧杯, 为其提供一个潮湿的环境(其后所有培养箱均具有此潮湿环境)。

1.4 DMEM/F-12培养ARFTM培养后的样品, 通过卢戈氏碘液染色后, 用光学显微镜观察。选取其中侵染程度最高的组, 6 000 r/min离心10 min, 去除上清液。无菌海水冲洗沉淀物, 6 000 r/min离心10 min, 去除上清液, 此过程重复至少2次。加入适量已配置好的DMEM/F-12-3培养基[20], 使休眠孢子悬浮于培养基中。

1.5 物理因素胁迫实验吸取1.5×105个休眠孢子, 加到24孔培养板中, 每孔添加2 mL DMEM/F-12培养基, 每组实验条件设置3个平行对照。每2 d吸取20 μL于载玻片, 显微镜下计数, 重复3次, 并计算出对应总数。实验条件如下:

根据派琴虫的最适培养条件[21], 设置对照组为最适条件组0: 培养温度28 ℃, 盐度25。

实验组A: 固定盐度为25, 20 ℃中培养2 d, 转入28 ℃培养2 d, 再返回20 ℃培养2 d, 如此循环;

实验组B: 固定盐度为25, 置于35 ℃中培养2 d, 转入28 ℃中培养2 d, 再返回35 ℃培养2 d, 如此循环;

实验组C: 固定温度为28 ℃, 盐度20中培养2 d, 调节盐度至25培养2 d, 再返回20培养2 d, 如此循环;

实验组D: 固定温度为28 ℃, 盐度35中培养2 d, 调节盐度至25培养2 d, 再返回35培养2 d, 如此循环;

实验组E: 在20、20 ℃中培养2 d, 随后转入25、28 ℃培养2 d, 再转入初始状态培养2 d, 如此循环;

实验组F: 在35、35 ℃中培养2 d, 随后转入25、28 ℃培养2 d, 再返回初始培养2 d, 如此循环;

实验组G: 固定温度为28 ℃、固定盐度为25、转速200 r/min。

对于实验组的升温和降温在15 min内完成。

1.6 数据分析体外培养的派琴虫用生物光学显微镜DM-LB2(德国徕卡)进行观察和拍照记录; 收集到的派琴虫孢子液, 吸取10 μL计数, 重复3次计数以计算平均值, 然后计算出总体积的培养基中含有的休眠孢子总数: 计数公式=平均个数N×稀释倍数。所得到的数据用Microsoft Visual C++ 6.0进行作图。

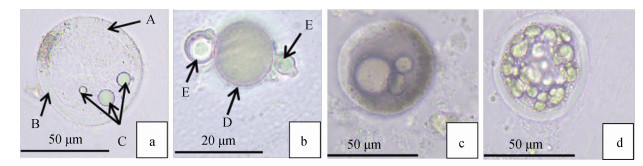

2 结果 2.1 派琴虫体外生活史及其细胞内容物变化 2.1.1 休眠孢子阶段ARFTM培养阶段, 随培养时间增加, 派琴虫细胞个体直径增加到20~60 μm, 形成休眠孢子, 此阶段其细胞壁随培养时间的增长而增厚。休眠孢子内部含有一个或多个折光体(类脂微粒), 大部分的休眠孢子起初含有1~3个折光体, 部分含有更多。折光体也随培养时间的延长而增多, 通常呈簇状, 紧贴细胞膜的位置聚集。大多数情况下折光体只会聚集在细胞膜的一侧, 随后逐渐充满整个细胞(图 1)。休眠孢子在ARFTM培养基中一般不进行增殖, 只出现体积增大、细胞壁增厚现象。

|

| 图 1 休眠孢子转变为游动孢子囊 Fig. 1 Hypnospore transformed into a zoosporangium 注: a为休眠孢子, A. 细胞膜, B. 细胞壁, C. 折光体; b为前游动孢子囊, D. 母细胞, E. 分裂出的子孢子; c为游动孢子囊中4倍体的形成; d为游动孢子囊 |

从ARFTM培养基转至DMEM/F-12培养基后, 其内部的折光体相互融合成一个整体, 最终充斥整个细胞, 随后细胞内开始孕育新的子孢子。子孢子成熟后, 细胞膜会破裂一个小口释放子孢子, 释放的子孢子体积较小, 直径为5~20 μm, 我们将这一阶段称为前游动孢子囊阶段。在此阶段过程中, 子孢子大多以出芽增殖的方式进行增殖(图 1)。

2.1.3 游动孢子阶段前游动孢子囊细胞内部的营养物质不断增加, 细胞壁内开始形成2倍体, 随后分裂成4倍、8倍、16倍体等, 此阶段称为游动孢子囊, 如图 1所示。

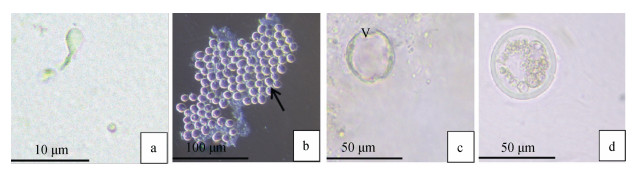

并非所有的游动孢子囊都进行新孢子的孕育, 有一部分细胞也通过二分裂的方式进行增殖, 其分裂出的子细胞也会进行二分裂产生新的子细胞。随着子细胞成熟, 细胞壁上形成一个管状的椭圆形凸起, 称为释放孔。细胞壁通过释放孔将成熟的子孢子释放到细胞体外, 以孢子增殖的方式进行增殖。释放的成熟子孢子称为游动孢子, 具双鞭毛, 能自由游动, 但体积较小, 有长尾巴, 如图 2所示。游动孢子长4~6 μm, 直径2~3 μm。

|

| 图 2 游动孢子转变成营养体 Fig. 2 Zoospore transformed into trophozoites 注: a为游动孢子; b为光镜偏振光下的细胞, 箭头表示刚出现偏心囊泡; c为偏心囊泡(如图中V所示); d为成熟的营养体 |

滋养体阶段, 一般是指游动孢子侵入到宿主体内的阶段。在此阶段中, 游动孢子逐渐发生变态, 形成一个圆形或者椭圆形细胞, 随后在细胞内开始聚集大量不透明的营养物质, 直至充满整个细胞, 而在细胞外侧会有一层透明的光圈, 将细胞整个包裹起来。随着细胞的发育, 其内部逐渐形成一个液泡似的空泡, 我们称其为偏心囊泡, 起初这个囊泡很小, 随着细胞进一步成熟, 其囊泡逐渐占据细胞绝大多数体积。此阶段中, 滋养体内部通过连续的二分裂产生大量子孢子, 子孢子聚集形成一个类似戒指的环状结构, 如图 2所示。滋养体成熟后称营养孢子, 随着细胞内部子细胞的增多, 营养孢子的细胞壁破碎, 释放其中的子孢子(不成熟的游动孢子), 这些孢子在体外继续发育, 最终变成成熟的滋养体。

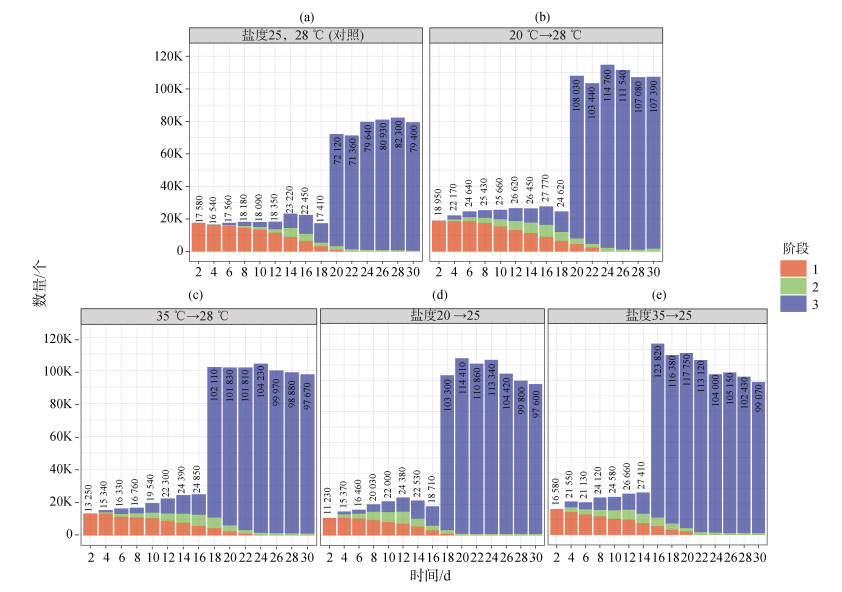

2.2 温度变化、盐度变化、震荡对北海派琴虫体外扩增的影响 2.2.1 温度变化对北海派琴虫体外扩增的影响实验条件A、B的结果如图 3所示。派琴虫从休眠孢子到滋养体阶段, 条件A需培养20 d; 条件B需培养18 d。将这2个实验组与对照组(条件0)对比发现, 单一的温度变化, 并没有明显引起派琴虫激增时间的变化。

|

| 图 3 温度、盐度变化对派琴虫生长的影响 Fig. 3 Effect of temperature and salinity changes on the growth of P. beihaiensis 注: a为对照组; b为条件A; c为条件B; d为条件C; e为条件D; 1表示休眠孢子阶段; 2表示前游动孢子囊阶段; 3表示滋养体阶段 |

派琴虫从休眠孢子生长到滋养体, 条件B比A时间更短(2 d)。但总体而言, 这2种温度变化的刺激对派琴虫生长速度变化无显著差异。

2.2.2 盐度变化对北海派琴虫体外扩增的影响实验条件C、D的结果如图 3所示。派琴虫从休眠孢子生长到滋养体阶段, 条件C需培养18 d; 条件D需培养16 d。将这2个实验组与对照组对比发现, 这2个条件的变化对派琴虫的生长均产生一定程度的刺激, 使其生长加快。条件C派琴虫的激增时间比对照组快了2 d; 条件D派琴虫的激增时间比对照组快了4 d。所以盐度单一条件的变化, 对派琴虫的激增存在一定的影响, 但影响程度不大。

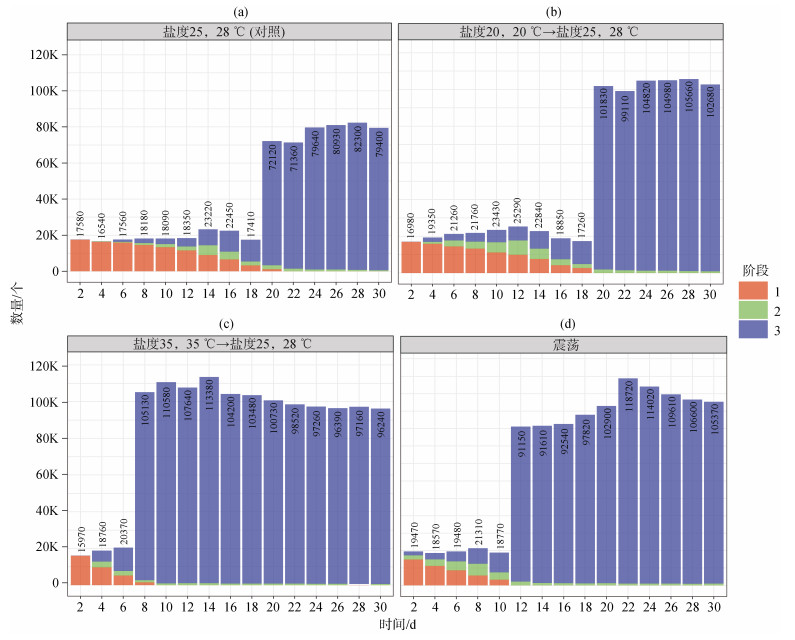

2.2.3 盐度和温度协同变化对北海派琴虫生长的影响实验条件E、F的结果如图 4所示。派琴虫从休眠孢子生长到滋养体阶段, 条件E需培养20 d; 条件F需培养8 d。将这2个实验组与对照组对比, 条件E派琴虫激增的时间与对照组无显著差异, 但数量比对照组多了1/5; 实验条件F派琴虫激增的时间与对照组相比, 其激增时间缩短了2.5倍; 其最终的激增数量, 比对照组多了1/5。可以明显看出, 在条件F下派琴虫生长得到了明显的刺激。

|

| 图 4 温度和盐度协同变化及震荡对派琴虫生长的影响 Fig. 4 Effect of coordinated temperature and salinity changes and shock on the growth of P. beihaiensis 注: a为对照组; b为条件E; c为条件F; d为条件G; 1表示休眠孢子阶段; 2表示前游动孢子囊阶段; 3表示滋养体阶段 |

当派琴虫处于培养条件F时, 其激增时间比培养条件E提前了12 d, 即提前了1/2。这说明当盐度和温度同时升高时, 派琴虫的生长未受到很大的刺激作用。但当盐度和温度同时降低时, 派琴虫的生长受到很大的刺激作用, 使其快速增殖。

2.2.4 震荡对北海派琴虫体外培养的影响实验条件G的结果如图 4所示, 派琴虫从休眠孢子生长到滋养体阶段, 条件G需培养12 d。对比对照组, 其培养时间缩短了8 d; 其最终的激增数量, 比对照组多1/4左右。说明震荡条件对派琴虫的生长, 具有显著的刺激作用, 能促使派琴虫更快地繁殖发育。

3 讨论 3.1 前游动孢子囊阶段分析在派琴虫生活史的4个阶段中, 滋养体是在宿主体内存在最长的阶段, 也是引起宿主死亡最主要的阶段[22]。体外培养派琴虫时, 首先是从滋养体发育到休眠孢子, 再发育成游动孢子囊, 随后形成游动孢子, 最终游动孢子失去双鞭毛等特性转变成滋养体, 达成一个循环[23]。感染派琴虫后, 宿主生长缓慢, 生殖量减少, 宿主组织萎缩或溶解, 通常在牡蛎达到生殖成熟后死亡[24]。派琴虫侵染有个重要特征就是其生活史中的任意阶段都可以感染宿主, 也都具有毒力[25], 所以派琴虫是一种极其容易寄生的原生动物。但曾有研究表明, 体外培养的派琴虫的毒力, 要明显低于自然界中的毒力[26]。

本实验在体外培养的P. beihaiensis, 其主要的生活史与其他几种派琴虫的生活史一致, 唯一不同的是在本实验中观察到P. beihaiensis前游动孢子囊时期, 该阶段与其他派琴虫种在形态学上存在明显的差异。处于此阶段的细胞呈半透明球形, 细胞体积偏小, 不易观察, 且有时也进行二分裂。曾有研究表明, 不同的派琴虫种之间, 休眠孢子最终释放游动孢子的过程是存在差异的[27], 所以我们认为此阶段是P. beihaiensis为适应新的生长环境条件而出现, 通过出芽增殖的方式使得其在新的环境中更快繁殖。但此阶段是否普遍存在P. beihaiensis之间, 还需要后续试验证明。

3.2 物理因素对派琴虫体外培养影响的分析温度、盐度、震荡这些物理条件对派琴虫的感染影响显著[28]。如Binias等[29]在法国的低盐度地区(盐度23)发现派琴虫的流行率和强度都很低; Waki[30]发现在低盐条件下, 派琴虫的感染强度明显降低; P. marinus对极端的温度(15~35 ℃), 盐度(5~35)敏感[31]; 在离体培养中, 低渗透压降低了P. chesapeaki的游动孢子密度, 增加了滋养体密度[32]; 在韩国马尼拉蛤中分离到的Perkinsus sp. 的游动孢子囊在冬季10~30℃和渗透压5~30 spu释放游动孢子, 而在夏季分离到的Perkinsus sp. 的游动孢子在20~30℃和15~30 spu下释放游动孢子[33]等。

因在自然环境中, 温度和盐度条件在时间和空间上存在差异, 研究环境条件对游动孢子形成的影响具有重要意义, 所以本实验旨在模拟自然界水体的温度、盐度、水的波动等外在条件进行研究。因在自然条件下环境因素都是连锁变化, 所以本实验叠加了盐度和温度两个物理因素。派琴虫宿主的生长条件一般为20~35℃、盐度20~35, 故本实验只选取温度范围为20~35℃、盐度范围20~35, 每组实验条件都设置3个平行对照。

本实验结果得出, 当温度和盐度产生变化时, 会对派琴虫的生长起到促进作用, 但仅温度或盐度等单一变量发生变化时, 起不到促进作用。但当温度和盐度同时下降时, 会显著地促进派琴虫生长。而确有报道表明派琴虫病在夏季是多发季节[34], 因为夏季温度高且降雨较多, 降雨会使水体温度和盐度都降低, 这就和我们的实验结果相呼应, 这对于派琴虫病的防控具有一定的指导意义。之所以会产生这样结果, 我们猜测是因为外界条件的改变, 刺激了派琴虫种群之间产生了某些化学信号, 因为确有研究曾报道过派琴虫在不同温度和盐度下体内蛋白表达量发生改变[35]。本实验添加震荡条件是为了模拟海水的波动情况, 从结果来看, 确实对派琴虫的生长起到积极作用, 我们认为在震荡条件下, 派琴虫体接触营养物质更充分, 虫体之间产生的化学信号传播得更快更宽广。

3.3 派琴虫体外培养方法的优化从本实验的结果得出, 在进行派琴虫体外培养时, 让其处在一个温度和盐度变化的环境中且适当的添加震荡条件, 会明显地刺激派琴虫的快速增殖, 所以本实验对派琴虫的体外培养方法进行了优化。

在进行派琴虫的体外培养时, 先将其置于最适的培养条件中培养一段时间, 使其适应新环境, 随后将培养温度和盐度适当升高培养一段时间, 使派琴虫得到刺激。然后将盐度和温度调回最适条件, 让派琴虫在高温高盐和最适条件之间反复转换, 从而给其足够的刺激, 在培养过程中也要高频地给予派琴虫添加震荡条件。

3.4 抗生素对派琴虫体外扩增影响的分析RFTM培养基是国际认可的用于培养派琴虫的标准培养基, 但其培养周期过长, 一般在7 d甚至更长的时间才能看到直径明显增大的休眠孢子[36]。而ARFTM培养基是一种可替代RFTM的培养基, 其培养时间短, 仅需48 h左右就可以看到休眠孢子直径增大现象[37]。所以本实验采用ARFTM培养基来培养, 使其可以更快地达到培养的目的。但在培养过程中发现, 适当延长培养ARFTM的培养时间, 可以促使派琴虫在DME/F12培养基中快速分裂。

ARFTM培养基和RFTM培养基的组成成分并没有太大的变化, 两者唯一明显的差别, 就在于添加抗生素的量, 而且用DMEM/F-12进行体外培养时, 适当减少抗生素的量也能提高派琴虫的生长速率。MOSS等人在长达数十年的研究中也发现在体外扩增派琴虫的过程中要不断的减少抗生素的浓度[38]。因此推测, 抗生素的添加量会对派琴虫的发育产生一定的阻碍作用。

综上所述, P. beihainensis在体外培养时, 其生活史在休眠孢子阶段后出现前游动孢子囊阶段。在体外培养时, 温度和盐度从35 ℃、35 ppt变化至38 ℃、28 ppt时, P. beihainensis仅8 d就达到快速扩增, 比传统的培养时间减少了一半; 当只添加震荡条件时, P. beihainensis在12 d达到快速扩增, 比传统时间减少了1/3。本实验为派琴虫的季节性防控, 提供了重要参考依据, 在突发降雨时, 要注意防控奥尔森派琴虫病的发生。

| [1] |

吴霖, 叶灵通, 姚托, 等. 广西沿海贝类寄生帕金虫的宿主多样性及季节动态[J]. 南方水产科学, 2018, 14(6): 113-117. WU Lin, YE Lingtong, YAO Tuo, et al. Species diversity and seasonal occurrence of Perkinsus spp. in shellfish along coastal area of Guangxi[J]. South China Fisheries Science, 2018, 14(6): 113-117. |

| [2] |

SOUDANT P, CHU F L E, VOLETY A. Host–parasite interactions: Marine bivalve molluscs and protozoan parasites, Perkinsus species[J]. Journal of Invertebrate Pathology, 2013, 114(2): 196-216. DOI:10.1016/j.jip.2013.06.001 |

| [3] |

DE LA HERRAN R, GARRIDO-RAMOS M A, NAVAS J I, et al. Molecular characterization of the ribosomal RNA gene region of Perkinsus atlanticus: its use in phylogenetic analysis and as a target for a molecular diagnosis[J]. Parasitology, 2000, 120(4): 345-353. DOI:10.1017/S003118209900565X |

| [4] |

HUANG Z, CAMPBELL D A, STURM N R, et al. Spliced leader RNAs, mitochondrial gene frameshifts and multi-pro-tein phylogeny expand support for the genus Perkinsus as a unique group of alveolates[J]. PLoS One, 2011, 6(5): e19933. DOI:10.1371/journal.pone.0019933 |

| [5] |

RAY S M. Historical perspective on Perkinsus marinus disease of oysters in the Gulf of Mexico[J]. Shellfifish Res, 1996, 15(1): 9-11. |

| [6] |

WAKI T, SHIMOKAWA J, WATANABE S, et al. Experimental challenges of wild Manila clams with Perkinsus species isolated from naturally infected wild Manila clams[J]. Journal of Invertebrate Pathology, 2012, 111(1): 50-55. DOI:10.1016/j.jip.2012.05.009 |

| [7] |

LUZ CUNHA A C, PONTINHA V D, DE CASTRO M A M, et al. Two epizootic Perkinsus spp. events in commercial oyster farms at Santa Catarina[J]. Brazil Journal of Fish Diseases, 2019, 42(3): 455-463. DOI:10.1111/jfd.12958 |

| [8] |

VILLALBA A, REECE K S, ORDÁS M C, et al. Perkinsosis in molluscs: a review[J]. Aquatic Living Resources, 2004, 17(4): 411-432. DOI:10.1051/alr:2004050 |

| [9] |

MOSS J A, XIAO Jie, DUNGAN C F, et al. Description of Perkinsus beihaiensis n. sp. a new Perkinsus sp. Parasite in Oysters of Southern China[J]. Journal of Eukaryotic Microbiology, 2010, 55(2): 117-130. |

| [10] |

DINESH G, SEUNG-HYEON K, KWANG-SIK C, et al. Scanning electron microscopic observation of the in vitro cultured protozoan, Perkinsus olseni, isolated from the Manila Clam, Ruditapes philippinarum[J]. BioMed Central Microbiology, 2020, 20(1): 1-9. |

| [11] |

HASANUZZAMAN A F M, ASUNCIÓN C, PAOLO R, et al. New insights into the Manila clam–Perkinsus olseni interaction based on gene expression analysis of clam hemocytes and parasite trophozoites through in vitro challenges[J]. International Journal for Parasitology, 2020, 50(3): 195-208. DOI:10.1016/j.ijpara.2019.11.008 |

| [12] |

王芳, 黄纪徽, 顾志峰, 等. 海洋贝类帕金虫及其病害发生[J]. 基因组学与应用生物学, 2009, 28(3): 583-593. WANG Fang, HUANG Jiwei, GU Zhifeng, et al. Perkinsus sp. and its disease occurrence[J]. Genomics and Applied Biology, 2009, 28(3): 583-593. |

| [13] |

AUZOUX-BORDENAVE S, VIGARIO A M, RUANO F, et al. In vitro sporulation of the clam pathogen Perkinsus atlanticus (Apicomplexa, Perkinsea) under various environmental conditions[J]. Journal of Shellfish Research, 1995, 14(14): 469-475. |

| [14] |

DUNGAN C F, REECE K S, MOSS J A, et al. Perkinsus olseni in vitro isolates from the New Zealand clam Austrovenus stutchburyi[J]. Journal of Eukaryotic Microbiology, 2007, 54(3): 263-270. DOI:10.1111/j.1550-7408.2007.00265.x |

| [15] |

ORDÁS M C, FIGUERAS A. In vitro culture of Perkinsus atlanticus, a parasite of the carpet shell clam Ruditapes decussatus[J]. Dis. Aquat. Org, 1998, 33(2): 129-136. |

| [16] |

ALMEIDA M, BERTHE F, THÉBAULT A, et al. Whole clam culture as a quantitative diagnostic procedure of Perkinsus atlanticus (Apicomplexa, Perkinsea) in clams Ruditapes decussatus[J]. Aquaculture, 1999, 177(1/4): 325-332. |

| [17] |

DUNGAN C F, HAMILTON R M. Use of a Tetrazolium-based cell proliferation assay to measure effects of in vitro cconditions on Perkinsus marinus (Apicomplexa) proliferation[J]. Journal of Eukaryotic Microbiology, 1995, 42(4): 379-388. DOI:10.1111/j.1550-7408.1995.tb01598.x |

| [18] |

CASAS S M, GRAU A, REECE K S, et al. Perkinsus mediterraneus n. sp., a protistan parasite of the European flat oyster Ostrea edulis from the Balearic Islands, Mediterranean Sea[J]. Diseases of aquatic organisms, 2004, 58(2-3): 231-244. |

| [19] |

NICKENS A D, LA PEYRE J F, WAGNER E S, et al. An improved procedure to count Perkinsus marinus in eastern oyster hemolymph[J]. Journal of Shellfish Research, 2002, 21(2): 725. |

| [20] |

DUNGAN C F, REECE K S. In vitro propagation of two Perkinsus spp. parasites from Japanese Manila clams Venerupis philippinarum and description of Perkinsus honshuensis n. sp.[J]. Journal of Eukaryotic Microbiology, 2006, 53(5): 316-326. DOI:10.1111/j.1550-7408.2006.00120.x |

| [21] |

QUEIROGA F R, MARQUES-SANTOS L F, DE MEDEIROS I A, et al. Effects of salinity and temperature on in vitro cell cycle and proliferation of Perkinsus marinus from Brazil[J]. Parasitology, 2016, 143(4): 475-487. DOI:10.1017/S0031182015001602 |

| [22] |

BOX A, CAPÓ X, TEJADA S, et al. Perkinsus mediterraneus infection induces oxidative stress in the mollusc Mimachlamys varia[J]. Journal of Fish Diseases, 2019, 43(1): 1-7. |

| [23] |

WANG Y, YOSHINAGA T, ITOH N. New insights into the entrance of Perkinsus olseni in the Manila clam, Ruditapes philippinarum[J]. Journal of invertebrate pathology, 2018, 153: 117-121. DOI:10.1016/j.jip.2018.03.005 |

| [24] |

PROESTOU D A, SULLIVAN M E. Variation in global transcriptomic response to Perkinsus marinus infection among eastern oyster families highlights potential mechanisms of disease resistance[J]. Fish and Shellfish Immunology, 2020, 96: 141-151. DOI:10.1016/j.fsi.2019.12.001 |

| [25] |

WU L, YE L T, WANG Z R, et al. Utilization of recombinase polymerase amplification combined with a lateral flow strip for detection of Perkinsus beihaiensis in the oyster Crassostrea hongkongensis[J]. Parasites and Vectors, 2019, 12(1): 1-8. DOI:10.1186/s13071-018-3256-z |

| [26] |

BUSHEK D, FORD S, CHINTALA M. Comparison of in vitro-cultured and wild-type Perkinsus marinus. Ⅲ. Fecal elimination and its role in transmission[J]. Diseases of Aquatic Organisms, 2002, 51(3): 217-225. |

| [27] |

LA PEYRE M, CASAS S M, LA PEYRE J F. Salinity effects on viability, metabolic activity and proliferation of three Perkinsus species[J]. Diseases of Aquatic Organisms, 2006, 71(1): 59-74. |

| [28] |

梁玉波, 张喜昌, 陈红星, 等. 温度盐度对菲律宾蛤仔帕金虫病害发生的影响[J]. 海洋环境科学, 2008, 27(1): 3-7. LIANG Yubo, ZHANG Xichang, CHEN Hongxing, et al. Effects of temperture and salinity on Perkinsus atlanticus disease triggering of clams Ruditapes philippinarum[J]. Marine Environmental Science, 2008, 27(1): 3-7. |

| [29] |

BINIAS C, DO V T, JUDE-LEMEILLEUR F, et al. Environmental factors contributing to the development of brown muscle dis ease and perkinsosis in Manila clams (Ruditapes philippinarum) and trematodiasis in cockles (Cerastoderma edule) of Arcachon Bay[J]. Marine Ecology, 2014, 35(1): 67-77. |

| [30] |

WAKI T, YOSHINAGA T. Suppressive effects of low salinity and low temperature on in-vivo propagation of the protozoan Perkinsus olseni in Manila clam[J]. Fish Pathology, 2015, 50(1): 16-22. |

| [31] |

QUEIROGA F R, MARQUES-SANTOS L F, MEDEIROS I D, et al. Effects of salinity and temperature on in vitro cell cycle and proliferation of Perkinsus marinus from Brazil[J]. Parasitology, 2016, 143(4): 475-487. |

| [32] |

CASAS S M, LA PEYRE J F. Identifying factors inducing trophozoite differentiation into hypnospores in Perkinsus species[J]. European journal of protistology, 2013, 49(2): 201-209. |

| [33] |

AHN K, KIM K. Effect of temperature and salinity on in vitro zoosporulation of Perkinsus sp. in Manila clams Ruditapes philippinarum[J]. Diseases of Aquatic Organisms, 2001, 48(1): 43-46. |

| [34] |

LUZ M S A, CARVALHO F S, OLIVEIRA H C, et al. Perkinsus beihaiensis (Perkinsozoa) in oysters of Bahia State, Brazil[J]. Brazilian Journal of Biology, 2018, 78(2): 289-295. |

| [35] |

PINTO T R, BOEHS G, PESSOA W F B, et al. Detection of Perkinsus marinus in the oyster Crassostrea rhizophorae in southern Bahia by proteomic analysis[J]. Brazilian Journal of Veterinary Research and Animal Science, 2017, 53(4): 1-4. |

| [36] |

RAY S. M, MACKIN J. G, BOSWELL J L. Quantitative measurement of the effect on oysters of disease caused by Dermocystidium Marinum[J]. Bulletin of Marine Science Miami, 1953, 3(1): 6-33. |

| [37] |

BURRESON E M, REECE K S, DUNGAN C F. Molecular, morphological, and experimental evidence support the synonymy of Perkinsus chesapeaki and Perkinsus andrewsi[J]. Journal of Eukaryotic Microbiology, 2005, 52(3): 258-270. |

| [38] |

CASAS S M, REECE K S, LI Y L, et al. Continuous culture of Perkinsus mediterraneus, a parasite of the European flat oyster Ostrea edulis, and characterization of its morphology, propagation, and extracellular proteins in vitro[J]. Journal of Eukaryotic Microbiology, 2008, 55(1): 34-43. |

2023, Vol. 47

2023, Vol. 47