文章信息

- 石一茜, 戴小杰, 朱江峰. 2023.

- SHI Yi-qian, DAI Xiao-jie, ZHU Jiang-feng. 2023.

- 中西太平洋延绳钓渔业鲸类兼捕的空间变化及其环境影响

- Spatial variation and environmental effects of concurrent whaling in longline fisheries in the Central and Western Pacific

- 海洋科学, 47(4): 145-154

- Marine Sciences, 47(4): 145-154.

- http://dx.doi.org/10.11759/hykx20220512003

-

文章历史

- 收稿日期:2022-05-12

- 修回日期:2022-07-11

2. 大洋渔业资源可持续开发教育部重点实验室, 上海 201306;

3. 农业农村部大洋渔业开发重点实验室, 上海 201306;

4. 国家远洋渔业工程技术研究中心, 上海 201306

2. Key Laboratory of Sustainable Exploitation of Oceanic Fisheries Resources, Ministry of Education, Shanghai 201306, China;

3. Key Laboratory of Oceanic Fisheries Exploration, Ministry of Agriculture and Rural Affairs, Shanghai 201306, China;

4. National Engineering Research Center for Oceanic Fisheries, Shanghai 201306, China

气候变化和人类活动的累积影响对海洋系统造成压力, 挑战海洋生态系统的健康[1]。其中商业渔业的兼捕是一个日益突出的国际生态、社会和经济问题[2-3], 兼捕的副渔获物与海洋生态系统和商业渔业的经济生存能力紧密联系, 渔业的兼捕现象几乎涉及所有的现有渔具[4-5]。自20世纪90年代以来, 延绳钓渔业对鲸类的影响引起了全球关注[5-6], 作为顶级捕食者的鲸类, 它们对猎物种群和食物网产生广泛影响, 并构成深海和浅海系统之间的直接生态联系, 在维持海洋生物多样性和海洋生态系统功能方面至关重要。由于鲸类独特的生活史特征, 在渔业兼捕的压力下其死亡率高于自然水平, 进而导致海洋生态系统受到威胁[2, 7]。

延绳钓渔业在作业过程中, 鲸类通过掠食延绳钓饵料及渔获物[8], 在此过程中鲸类存在被钓绳缠绕及误捕的风险, 导致鲸类意外死亡或严重受伤。在中西太平洋海域, 来自48个国家的船队使用延绳钓渔具捕捞金枪鱼、类金枪鱼物种[9], 许多鲸类物种的空间分布与延绳钓渔业的渔场呈现显著重叠[10-12], 如Forney等[13]估计, 从1994—2005年, 夏威夷中上层延绳钓船队观察员数据中显示, 67头鲸类被钓钩钩住或被钓绳缠绕, 其中44头鲸类严重受伤, 7头鲸类死亡, 分别为2头短鳍领航鲸(Globicephala macrorhynchus)、2头伪虎鲸(Pseudorca crassidens)、1头热带点斑原海豚(Stenella attenuata)、1头瓶鼻海豚(Tursiops truncatus)、1头柏氏中喙鲸(Mesoplodon densirostris)。在美国南部剑鱼和金枪鱼的延绳钓渔业中, 短鳍领航鲸通常会被钓具缠绕[14]。在意大利海域, 小型齿鲸类如条纹原海豚(Stenella coeruleoalba), 里氏海豚(Grampus griseus)、瓶鼻海豚、抹香鲸(Physeter macrocephalus)均受到延绳钓钓具缠绕的影响[15]。Waring等[16]对美国墨西哥湾哺乳动物资源进行评估, 在1999—2003年间, 估计平均每年有132头领航鲸和45头里氏海豚与中上层延绳钓钓具相互作用而导致严重受伤甚至死亡。因此, 了解金枪鱼延绳钓渔业中兼捕鲸类的影响因素对鲸类采取合适的养护管理措施非常重要[17-18]。

目前, 有关中西太平洋金枪鱼渔业兼捕的研究主要集中在海鸟及海龟的兼捕[19-20], 有关鲸类物种的兼捕及其影响因素的研究较少。而鲸类的兼捕受多种影响因子共同作用, 简单的单因子分析和线性回归分析不能很好地解释其与渔业之间相互作用的机制, 近年来广义可加模型(generalized additive models, GAM)越来越多应用在鲸类种群的研究中。国外学者通过GAM的方法探究鲸类物种分布的时空特征及与环境因子之间的关系[21], Derville等[22]通过比较五种统计算法处理非系统性鲸类调查中常见偏差的能力, 证明GAM是一个可解释性和可推广性的预测分布模型。如Forney[23]利用GAM探究加利福尼亚海域对白腰鼠海豚(Phocoenoides dalli)和真海豚(Delphinus delphis)的分布与环境因子之间的关系, 结果表明GAM模型能够减少环境变化引起的不确定性并提高我们检测和解释鲸类种群变化趋势的能力。目前, 国内尚未将GAM模型应用于探究影响鲸类兼捕的因素。为此本文利用中西太平洋渔业委员会授权数据, 结合环境数据建立GAM模型, 分析以下3个问题, 1)金枪鱼延绳钓对哪些鲸类物种的兼捕率或影响较高?2)鲸类兼捕与金枪鱼单位捕捞努力量渔获量的关系如何?3)鲸类兼捕在空间上如何变化以及该变化是否受环境因素的影响?通过分析, 以期确定影响鲸类物种兼捕的因素, 从而为减少渔业兼捕鲸类提出科学建议。

1 材料和方法 1.1 数据来源本文研究区域为中西太平洋海域(42.5°S~42.5°N、117.5°E~132.5°W), 金枪鱼延绳钓渔获量数据源于中西太平洋渔业委员会(Western and Central Pacific Fishery Commission, WCPFC)的科学机构太平洋共同体秘书处(Secretariat of the Pacific Community, SPC), 鲸类兼捕数据来源于中西太平洋渔业委员会区域观察员计划(Regional Observer Programme, ROP), 经过授权由太平洋共同体秘书处提供, 该数据记录了鲸类兼捕时的位置(纬度和经度)、物种、数量和状态(死/活)。海面温度(sea surface temperature, SST)、叶绿素a浓度(Chlorophyll a concentration, Chl a)数据来自美国国家海洋和大气管理局(https://oceanwatch.pifsc.noaa.gov/), 时间分辨率为月。由于2020年COVID-19影响了世界上大多数国家, 并严重影响了渔业和水产养殖的生产分配和经济效应, 因此本文仅采用2013—2019年的鲸类兼捕数据、环境数据和渔业数据进行匹配。

1.2 研究方法 1.2.1 数据预处理数据分析前须对中西太平洋金枪鱼延绳钓渔获物和兼捕的鲸类数量进行标准化处理。渔获物(大眼金枪鱼、黄鳍金枪鱼和长鳍金枪鱼)和鲸类兼捕数据按照经纬度5°×5°的空间分辨率进行统计, 并按照年进行汇总。本文采用以年为单位的捕捞努力量渔获量(catch per unit effort, CPUE)和鲸类兼捕率(bycatch per unit effort, BPUE), 其公式为:

| CPUE=U/F, | (1) |

| BPUE=N/f, | (2) |

式中U为5°×5°渔区范围内金枪鱼年产量; F为5°×5°渔区范围内总钩数, N为5°×5°渔区范围内年兼捕鲸类个体数, f为5°×5°渔区范围内观察员记录的总钩数。海洋环境数据(SST、Chl-a), 以5°×5°为空间分辨率, 以年份为时间分辨率进行统计, 由于仅包含年际的鲸类兼捕数据, 因此将环境数据逐月平均后求得年均环境值。

1.2.2 GAM模型的建立利用GAM模型[7]对中西太平洋兼捕鲸类的影响因子进行分析, 计算公式为:

| BPUE∼s( Longitude )+s(SST)+s(Chl a)+s( Latitude )+s(CPUE)+ε, | (3) |

其中BPUE为鲸类副渔获率, s为自然立方样条平滑(Natural cube spline smoother), Longitude表示经度, Chl a表示叶绿素a质量浓度, SST表示海面温度, Latitude表示纬度, CPUE为捕捞努力量渔获量, ε为残差。采用方差膨胀因子(Variance Inflation Factor, VIF)检验共曲线性(Concurvity), 通过广义交叉验证(Generalized Cross Validation, GCV), 选择最小GCV的统计量, 以达到删除或者增加变量的目的, 同时考虑到记录的鲸类兼捕数据固有的过度分散性, 本文使用伪泊松GAM模型拟合每组鲸类副渔获率[24], 最后利用F检验评估解释变量的显著性。GAM的构建及检验通过R中的mgcv软件包实现[25]。

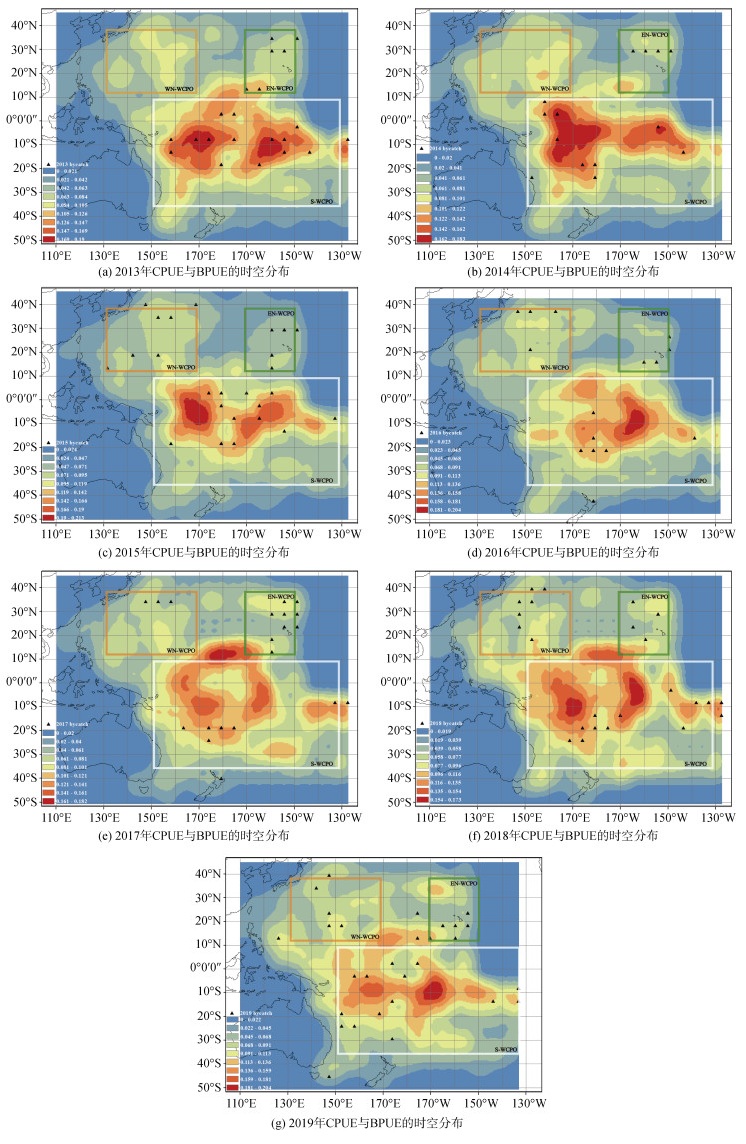

2 结果与分析中西太平洋延绳钓船队兼捕的副渔获物从2013—2019年共兼捕到472 177个海洋大型珍稀保护动物, 包括鱼类、海龟、海鸟和海洋哺乳动物, 其中鲸类占总副渔获物的0.05%, 共有260头鲸类物种被偶然捕获, 隶属于2目4科19种(附录1)。2013—2019年间观察到金枪鱼CPUE和BPUE的分布如图 1所示, 鲸类兼捕呈现较强的分散性, 兼捕热点主要集中在3个海域: (1)中西太平洋西北海域(WN-WCPO) 12.5°N~37.5°N, 132.5°E~167.5°E, (2)中西太平洋东北海域(EN-WCPO) 12.5°N~37.5°N, 172.5°W~152.5°W, (3)中西太平洋南部海域(S-WCPO) 37.5°S~7.5°N, 152.5°E~132.5°W, S-WCPO海域的兼捕率 > EN-WCPO海域兼捕率 > WN-WCPO海域的兼捕率。而在12.5°N~37.5°N, 162.5°E~ 177.5°E海域, 7年间未发现一例兼捕事件。在兼捕的热点海域常出现的鲸类物种包括伪虎鲸(25.0%)、齿鲸亚目(19.6%)、瓶鼻海豚(9.6%)、短鳍领航鲸(8.5%)、糙齿海豚(5.8%)和里氏海豚(5.4%)。

| 物种 | 拉丁学名 | 兼捕个数 |

| 瓶鼻海豚 | Tursiops truncatus | 25 |

| 蓝鲸 | Balaenoptera musculus | 1 |

| 原海豚 | Delphinus delphis | 4 |

| 侏儒抹香鲸 | Kogia simus | 1 |

| 伪虎鲸 | Pseudorca crassidens | 65 |

| 银杏齿喙鲸 | Mesoplodon ginkgodens | 1 |

| 座头鲸 | Megaptera novaeangliae | 1 |

| 印太洋瓶鼻海豚 | Tursiops aduncus | 9 |

| 长喙真海豚 | Delphinus capensis | 1 |

| 瓜头鲸 | Peponocephala electra | 10 |

| 热带点斑原海豚 | Stenella attenuata | 5 |

| 小虎鲸 | Feresa attenuata | 5 |

| 小抹香鲸 | Kogia breviceps | 3 |

| 里氏海豚 | Grampus griseus | 14 |

| 糙齿海豚 | Steno bredanensis | 15 |

| 短鳍领航鲸 | Globicephala macrorhynchus | 22 |

| 抹香鲸 | Physeter macrocephalus | 4 |

| 飞旋原海豚 | Stenella longirostris | 7 |

| 条纹原海豚 | Stenella coeruleoalba | 3 |

| 海豚科 | Delphinidae | 2 |

| 喙鲸科 | Ziphiidae | 3 |

| 齿鲸亚目 | Odontoceti | 51 |

| 鲸类 | Cetacea | 8 |

|

| 图 1 2013—2019年中西太平洋金枪鱼CPUE与鲸类BPUE的时空分布 Fig. 1 Temporal and spatial distributions of CPUE and BPUE in the Central and Western Pacific from 2013 to 2019 |

为了检验模型中每个因子的重要性及遴选最优模型(表 1), 该模型最终对BPUE的总偏差解释率为71.7%, 所有因子中, 经度的贡献率最大为34.3%, 其次为SST、Chl a、纬度、CPUE, 贡献率分别为15.3%、12%、7.9%、2.2%。F检验表明所有模型因子均与BPUE呈显著相关关系, 随着因子的不断加入GCV值降低, 最终保留所有影响因子。

| 模型因子 | 估计自由度 | 参考自由度 | F值 | P值 | 累积解释偏差/% | GCV |

| 经度 | 8.416 | 8.888 | 12.881 | < 2e-16 *** | 34.3% | 0.004 294 2 |

| 海表温度 | 8.413 | 8.876 | 6.610 | < 2e-16 *** | 49.6% | 0.003 601 2 |

| 叶绿素a浓度 | 5.679 | 6.795 | 9.553 | < 2e-16 *** | 61.6% | 0.002 943 8 |

| 纬度 | 1.000 | 1.000 | 16.961 | 6.09e-05 *** | 69.5% | 0.002 610 1 |

| 捕捞努力量渔获量 | 6.565 | 7.661 | 5.572 | 6.45e-06 *** | 71.7% | 0.002 376 9 |

| 注: ***表示极显著水平 | ||||||

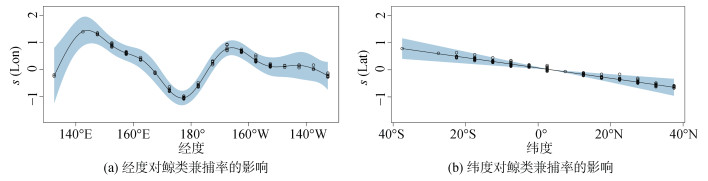

空间因子(经度、纬度)与BPUE的关系中(图 2), 以180°E为界分为两个部分, 在132.5°E~142.5°E间BPUE有显著上升的趋势, 142.5°E~177.5°E间, BPUE随经度的增加呈明显的下降趋势[图 2(a)], 在>180°E的海域, 180°E~162.5°W海域BPUE呈明显的上升趋势, 在 > 162.5°W海域随经度的降低BPUE呈下降趋势。纬度对中西太平洋鲸类BPUE的影响呈明显的负相关线性关系[图 2(b)], 从南半球往北半球其BPUE显著下降。

|

| 图 2 空间因子对鲸类兼捕率的影响 Fig. 2 Effects of spatial factors on BPUE |

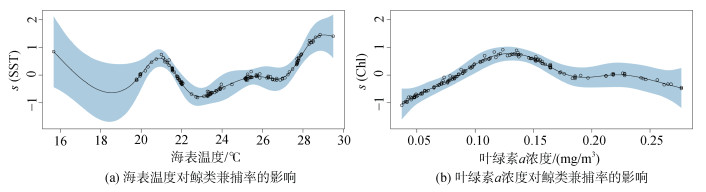

在环境因子(SST、Chl-a)中(图 3), SST与BPUE的关系最密切(表 1), 中西太平洋鲸类BPUE主要发生范围在20℃~29℃间[图 3(a)], 主要集中在海表温度为20~24℃间。当海表温度在20~22℃时, BPUE先升高后降低, 当海表温度在 > 22℃时, BPUE呈明显的上升趋势。对BPUE产生影响的叶绿素a浓度主要集中在0.02~0.2 mg/m3[图 3(b)], 在0.02~0.148 mg/m3间BPUE呈显著的上升趋势, > 0.148 mg/m3时BPUE随叶绿素a浓度的增加呈下降趋势。

|

| 图 3 环境因子对鲸类兼捕率的影响 Fig. 3 Effects of environmental factors on BPUE |

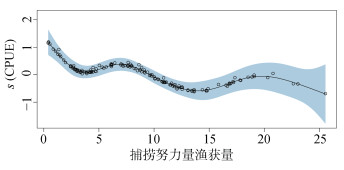

CPUE与鲸类BPUE的关系整体呈波浪状且下降的趋势(图 4), CPUE < 2.43时BPUE呈显著下降趋势, CPUE在2.43~7.01呈一定上升的趋势, 后随着CPUE的增加BPUE显著减少, 在CPUE > 14.90时, CPUE先上升后下降。

|

| 图 4 金枪鱼渔获率因子对鲸类兼捕率的影响 Fig. 4 Effects of CPUE factors on BPUE |

空间因子是影响海洋生物资源的重要环境因子之一[26-28], 经纬度对鲸类物种的影响呈极显著相关关系(表 1), 印证了鲸类物种具有随季节迁徙的全球性分布特征[28]。鲸类在中西太平洋海域的热点海域, 其中西北海域(WN-WCPO)出现鲸类兼捕热点主要受黑潮下层海水上涌的影响, 推动了该海域碳和营养物质的生物地球化学的循环, 进而增加了鲸类在该海域的丰度水平[29], 导致鲸类兼捕率相对较高。在中西太平洋东北海域(EN-WCPO)兼捕的伪虎鲸占比最高为36.23%, 该海域位于夏威夷岛屿附近, Bayless等[30]和Forney等[17]研究表明, 在夏威夷延绳钓渔业中伪虎鲸的兼捕率较高, 且已超过其潜在的生物可移除量(Potential Biological Removal level, PBR), 根据海洋哺乳动物保护法(Marine Mammal Protection Act, MMPA), 于2013年对夏威夷海域实施了减少兼捕伪虎鲸计划(Take Reduction Plan, TRP)并已取得成效[31]。中西太平洋南部海域(S-WCPO)包括22个太平洋岛国和澳大利亚大陆的一部分以及新西兰的南部岛屿, 该海域拥有庞大而复杂的海洋生态系统[32]。整体上, 兼捕事件在斐济和夏威夷周围海域发生的频率较高, 主要的兼捕对象是伪虎鲸、瓶鼻海豚、里氏海豚、短鳍领航鲸、糙齿海豚等, 后续应加快对频繁与延绳钓渔业相互作用的鲸类物种实施监管[17, 33]。

3.2 环境因子对中西太平洋鲸类兼捕率的影响效应在环境因子中, 海表温度是最容易观测的海洋物理因子, 同时水温的变化还可作为判断海流、水团、潮汐、渔场和基础生产力等物理特性变化的指标[34]。本研究中鲸类兼捕主要集中在21℃~29℃的海表温度范围内, 兼捕率最高的海域所对应的海表温度均值在24.28℃, 同时结合前人研究, 常见的兼捕鲸类物种如里氏海豚[35]、糙齿海豚[36]、短鳍领航鲸[37]、伪虎鲸[38]和瓶鼻海豚常出现在海表温度范围为12~25℃的海域, 这表明海表温度能较好地指示鲸类兼捕的热点海域。叶绿素a浓度的分析是应用基于海洋食物链原理, 即丰富的浮游植物会使以其为食的浮游动物资源量上升, 进而促使以浮游动物为饵料的海洋鱼类和鲸类物种的增加[39]。鲸类中包括须鲸亚目和齿鲸亚目, 须鲸主要是以磷虾或桡足类等小型浮游动物为食, 而齿鲸则主要以鱼类和头足类为食[40]。本文中鲸类BPUE较高的海域其叶绿素a浓度在0.02~0.2 mg/m3并集中在美拉尼亚群岛及其附近海域, 该海域被认定为全球生物多样性“热点”海域, 主要由群岛、岛屿、环礁和珊瑚礁组成[32], 在生态环境相对较好的珊瑚礁海域其叶绿素a质量浓度在0.2 mg/m3左右[41], 并表现出相对较高的总生产力, 存在大量稳定的中上层、底层和底栖鱼类及头足类[42-43], 为鲸类物种提供了大量营养供给, 使得在该海域中鲸类物种较为聚集。总体上, 海洋哺乳物种兼捕热点主要由环境因子所决定, 受到金枪鱼延绳钓渔业作业的影响相对较小, 其中海表温度主要影响鲸类的相对丰度, 叶绿素a浓度影响鲸类的分布。

3.3 金枪鱼渔获率因子对中西太平洋鲸类兼捕率的影响效应金枪鱼单位捕捞努力量渔获量(CPUE)对中西太平洋鲸类兼捕率的影响受到多种因素的影响, 如不同的延绳钓钓钩类型、大小、诱饵类型和作业深度对兼捕的鲸类物种也有所不同[11], 目前中西太平洋延绳钓渔业作业未能将鲸类兼捕与延绳钓作业相互作用的数据详细记录。因此, 鲸类兼捕的研究需进一步解决数据有限问题, 中西太平洋延绳钓单位捕捞努力量渔获量作为代表延绳钓渔业作业的因子对BPUE的影响仍须进一步评估。

3.4 减少延绳钓渔业兼捕鲸类的措施分析在中西太平洋海域, 由于鲸类分布范围广泛, 沿海和公海海域内人类活动及环境有所不同, 使得鲸类物种在整个海域内受渔业影响的程度存在差异。鲸类的分布通常取决于动态海洋环境间的相互作用, 如环境变化会协同生态学和流体力学特征将有机物质从海岸带流向远洋带, 从表面流向海域底部, 并促使鲸类猎物发生位移[44], 鲸类跟随猎物的变化进行转移。因此更应关注环境的变化及能量的流动, 结合鲸类活动轨迹如捕食、产仔、繁殖区域和迁徙路线[45]等, 将重点放在鲸类物种与延绳钓渔业的互动海域, 建立有效的鲸类兼捕减缓措施。同时, 为促进渔业管理和鲸类物种的保护, 未来须提高数据质量, 在进行渔业作业时, 提高船员对鲸类物种的识别释放及数据记录能力, 加强有关鲸类研究和数据共享方面的国际合作, 进而确保全球海洋生态系统和渔业的可持续性。

| [1] |

VISSER F, MERTEN V J, BAYER T, et al. Deep-sea predator niche segregation revealed by combined cetacean biologging and eDNA analysis of cephalopod prey[J]. Science Advances, 2021, 7(14): eabf5908. DOI:10.1126/sciadv.abf5908 |

| [2] |

HALL M A, ALVERSON D L, METUZALS K I. By-catch: problems and solutions[J]. Marine Pollution Bulletin, 2000, 41(1/6): 204-219. |

| [3] |

GILMAN E, BROTHERS N, KOBAYASHI D R. Principles and approaches to abate seabird by−catch in longline fisheries[J]. Fish and Fisheries, 2005, 6(1): 35-49. DOI:10.1111/j.1467-2679.2005.00175.x |

| [4] |

REEVES R R, READ A J, NOTARBARTOLO DI SICARA G. Report of the workshop on interactions between dolphins and fisheries in the Mediterranean: Evaluation of mitigation alternatives[R]. Istituto Centrale per la Riiiirca Applicata al Mare: Roma, Italy, 2001.

|

| [5] |

READ A J. Potential mitigation measures for reducing the by-catches of small cetaceans in ASCOBANS waters[R]//Report to ASCOBANS. Duke University, Beaufort NC, USA, 2000: 22.

|

| [6] |

GILMAN E, BROTHERS N, MCPHERSON G, et al. A review of cetacean interactions with longline gear[J]. Journal of Cetacean Research and Management, 2007, 8(2): 215. |

| [7] |

MANNOCCI L, DABIN W, AUGERAUD-VÉRON E, et al. Assessing the impact of bycatch on dolphin populations: the case of the common dolphin in the eastern North Atlantic[J]. PLoS one, 2012, 7(2): e32615. DOI:10.1371/journal.pone.0032615 |

| [8] |

WERNER T B, NORTHRIDGE S, PRESS K M C, et al. Mitigating bycatch and depredation of marine mammals in longline fisheries[J]. ICES Journal of Marine Science, 2015, 72(5): 1576-1586. DOI:10.1093/icesjms/fsv092 |

| [9] |

HARLEY S, WILLIAMS P, NICOL S, et al. The western and central Pacific tuna fishery: 2010 overview and status of stocks[R]//Tuna Fisheries Assessment Report 11. Noumea: Secretariat of the Pacific Community, 2011.

|

| [10] |

BAIRD R W, GORGONE A M. False killer whale dorsal fin disfigurements as a possible indicator of long-line fishery interactions in Hawaiian waters1[J]. Pacific Science, 2005, 59(4): 593-601. DOI:10.1353/psc.2005.0042 |

| [11] |

BRADFORD A L. Injury determinations for marine mammals observed interacting with Hawaii and American Samoa longline fisheries during 2015-2016[S]. PIFSC Technical Memorandum TM-NMFS-PIFSC-70. Pacific Islands Fisheries Science Center, National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration USA, 2018.

|

| [12] |

LÓPEZ D M, BARCELONA S G, BÁEZ J C, et al. Marine mammal bycatch in Spanish Mediterranean large pelagic longline fisheries, with a focus on Risso's dolphin (Grampus griseus)[J]. Aquatic living resources, 2012, 25(4): 321-331. DOI:10.1051/alr/2012038 |

| [13] |

FORNEY K A, KOBAYASHI D R. Updated estimates of mortality and injury of cetaceans in the Hawaii-based longline fishery, 1994-2005[R]. NOAA Technical Memorandum, NOAA-TM-NMFS-SWFSC-412, US Department of Commerce, 2007.

|

| [14] |

READ A J. Incidental catches of small cetaceans[M]//SIMMONDS M P, HUTCHINSON J D. The conservation of whales and dolphins: Science and practice. John Wiley and Sons Ltd, Chinchester, UK, 1996: 109-128.

|

| [15] |

BEARZI G. Interactions between cetacean and fisheries in the Mediterranean Sea[M]//di Sciara G N. Cetaceans of the Mediterranean and Black Seas: state of knowledge and conservation strategies. Monaco: ACCOBAMS, 2002.

|

| [16] |

WARING G T, JOSEPHSON E, FAIRFIFIELD C P, et al. U. S. Atlantic and Gulf of Mexico marine mammal stock assessments—2005[R]. NOAA Technical Memorandum NMFS-NE-194, 2006.

|

| [17] |

FORNEY K A, KOBAYASHI D R, JOHNSTON D W, et al. What's the catch? Patterns of cetacean bycatch and depredation in Hawaii-based pelagic longline fisheries[J]. Marine Ecology, 2011, 32(3): 380-391. DOI:10.1111/j.1439-0485.2011.00454.x |

| [18] |

LAIST D W, KNOWLTON A R, MEAD J G, et al. Collisions between ships and whales[J]. Marine Mammal Science, 2001, 17(1): 35-75. DOI:10.1111/j.1748-7692.2001.tb00980.x |

| [19] |

DEBSKI I, PIERRE J, KNOWLES K. Observer coverage to monitor seabird captures in pelagic longline fisheries[C]//Scientific Committee Twelfth Regular Session, Bali, Indonesia, 3-11 August 2016. Department of Conservation, JPEC Ltd, 2016: WCPFC-SC12-2016/EB-IP-07.

|

| [20] |

INOUE Y, YOKAWA K, MINAMI H, et al. Distribution of seabird bycatch at WCPFC and the neighboring area of the southern hemisphere[C]//Scientific Committee Seventh Regular Session, Pohnpei, Federated States of Micronesia, 9-17 August 2011. Ecologically Related Species Group, Tuna and Skipjack Resources Division, National Research Institute of Far Seas Fisheries, Fisheries Research Agency, 2011: WCPFC-SC7-2011/EB-WP-07.

|

| [21] |

牛明香, 李显森, 徐玉成. 基于广义可加模型的时空和环境因子对东南太平洋智利竹筴鱼渔场的影响[J]. 应用生态学报, 2010, 21(4): 1049-1055. NIU Mingxiang, LI Xiansen, XU Yucheng. Effects of spatiotemporal and environmental factors on the fishing ground of Trachurus murphyi in Southeast Pacific Ocean based on generalized additive model[J]. Chinese Journal of Applied Ecology, 2010, 21(4): 1049-1055. DOI:10.13287/j.1001-9332.2010.0155 |

| [22] |

DERVILLE S, TORRES L G, IOVAN C, et al. Finding the right fit: Comparative cetacean distribution models using multiple data sources and statistical approaches[J]. Diversity and Distributions, 2018, 24(11): 1657-1673. DOI:10.1111/ddi.12782 |

| [23] |

FORNEY K A. Environmental models of cetacean abundance: reducing uncertainty in population trends[J]. Conservation Biology, 2000, 14(5): 1271-1286. DOI:10.1046/j.1523-1739.2000.99412.x |

| [24] |

YEH Y M, HUANG H W, DIETRICH K S, et al. Estimates of seabird incidental catch by pelagic longline fisheries in the South Atlantic Ocean[J]. Animal Conservation, 2013, 16(2): 141-152. DOI:10.1111/j.1469-1795.2012.00588.x |

| [25] |

WOOD S N. Fast stable restricted maximum likelihood and marginal likelihood estimation of semiparametric generalized linear models[J]. Journal of the Royal Statistical Society: Series B (Statistical Methodology), 2011, 73(1): 3-36. DOI:10.1111/j.1467-9868.2010.00749.x |

| [26] |

BRAULIK G T, KASUGA M, WITTICH A, et al. Cetacean rapid assessment: An approach to fill knowledge gaps and target conservation across large data deficient areas[J]. Aquatic Conservation: Marine and Freshwater Ecosystems, 2018, 28(1): 216-230. DOI:10.1002/aqc.2833 |

| [27] |

REDFERN J V, MOORE T J, FIEDLER P C, et al. Predicting cetacean distributions in data‐poor marine ecosystems[J]. Diversity and Distributions, 2017, 23(4): 394-408. DOI:10.1111/ddi.12537 |

| [28] |

KASCHNER K. Modelling and mapping resource overlap between marine mammals and fisheries on a global scale[D]. University of British Columbia, Vancouver, Canada, 2004.

|

| [29] |

WONG G T F, CHAO S Y, LI Y H, et al. The Kuroshio edge exchange processes (KEEP) study-an introduction to hypotheses and highlights[J]. Continental Shelf Research, 2000, 20(4/5): 335-347. |

| [30] |

BAYLESS A R, OLESON E M, BAUMANN-PICKERING S, et al. Acoustically monitoring the Hawai 'i longline fishery for interactions with false killer whales[J]. Fisheries research, 2017, 190: 122-131. DOI:10.1016/j.fishres.2017.02.006 |

| [31] |

BAIRD R W, MAHAFFY S D, GORGONE A M, et al. False killer whales and fisheries interactions in Hawaiian waters: evidence for sex bias and variation among populations and social groups[J]. Marine Mammal Science, 2015, 31(2): 579-590. DOI:10.1111/mms.12177 |

| [32] |

MILLER C. Current state of knowledge of cetacean threats, diversity and habitats in the Pacific islands region[M]. WDCS Australasia Inc, 2007.

|

| [33] |

MILLER C, BATIBASAGA A, CHAND P, et al. Cetacean diversity, common occurrence and community importance in Fijian waters[J]. Pacific Conservation Biology, 2016, 22(3): 272-280. DOI:10.1071/PC14933 |

| [34] |

ZELLE H, APPELDOORN G, BURGERS G, et al. The relationship between sea surface temperature and thermocline depth in the eastern equatorial Pacific[J]. Journal of physical oceanography, 2004, 34(3): 643-655. DOI:10.1175/2523.1 |

| [35] |

WELLS R, MANIRE C, BYRD L, et al. Movements and dive patterns of a rehabilitated Risso's dolphin, Grampus griseus, in the Gulf of Mexico and Atlantic Ocean[J]. Publications, Agencies and Staff of the US Department of Commerce, 2009, 26. |

| [36] |

LODI L. Epimeletic behavior of free-ranging roughtoothed dolphins, Steno bredanensis, from Brazil[J]. Marine Mammal Science, 1992, 8(3): 284-287. DOI:10.1111/j.1748-7692.1992.tb00410.x |

| [37] |

FULLARD K J, EARLY G, HEIDE‐JøRGENSEN M P, et al. Population structure of long-finned pilot whales in the North Atlantic: a correlation with sea surface temperature?[J]. Molecular Ecology, 2000, 9(7): 949-958. DOI:10.1046/j.1365-294x.2000.00957.x |

| [38] |

ZAESCHMAR J R, VISSER I N, FERTL D, et al. Occurrence of false killer whales (Pseudorca crassidens) and their association with common bottlenose dolphins (Tursiops truncatus) off northeastern New Zealand[J]. Marine Mammal Science, 2014, 30(2): 594-608. DOI:10.1111/mms.12065 |

| [39] |

闫敏, 张衡, 伍玉梅, 等. 基于GAM模型研究时空及环境因子对南太平洋长鳍金枪鱼渔场的影响[J]. 大连海洋大学学报, 2016, 30(6): 681-685. YAN Min, ZHANG Heng, WU Yumei, et al. Effects of spatio-temporal and environmental factors on fishing grounds of albacore tuna Thunnus alalunga in the South Pacific Ocean based on generalized additive model[J]. Journal of Dalian Ocean University, 2016, 30(6): 681-685. DOI:10.16535/j.cnki.dlhyxb.2015.06.018 |

| [40] |

PERRIN W F, WÜRSIG B, THEWISSEN J G M. Encyclopedia of marine mammals[M]. Amsterdam, Netherland: Academic Press, 2009.

|

| [41] |

BELL P R F, ELMETRI I, LAPOINTE B E. Evidence of large-scale chronic eutrophication in the Great Barrier Reef: quantification of chlorophyll a thresholds for sustaining coral reef communities[J]. Ambio, 2014, 43(3): 361-376. DOI:10.1007/s13280-013-0443-1 |

| [42] |

GARCÍA‐MORALES R, PÉREZ‐LEZAMA E L, SHIRASAGO‐GERMÁN B. Influence of environmental variability on distribution and relative abundance of baleen whales(suborder Mysticeti)in the Gulf of California[J]. Marine Ecology, 2017, 38(6): e12479. DOI:10.1111/maec.12479 |

| [43] |

SMITH R C, DUSTAN P, AU D, et al. Distribution of cetaceans and sea-surface chlorophyll concentrations in the California Current[J]. Marine Biology, 1986, 91(3): 385-402. DOI:10.1007/BF00428633 |

| [44] |

WÜRTZ M, SIMARD F. Following the food chain: an ecosystem approach to pelagic protected areas in the mediterranean by mean of cetacean presence[J]. US Rapport de la Commission internationale pour la Mer Méditerranée, 2007, 38: 634. |

| [45] |

ALBOUY C, DELATTRE V L, MÉRIGOT B, et al. Multifaceted biodiversity hotspots of marine mammals for conservation priorities[J]. Diversity and Distributions, 2017, 23(6): 615-626. DOI:10.1111/ddi.12556 |

2023, Vol. 47

2023, Vol. 47