文章信息

- 高广, 肖志忠, 马文辉, 潘钊, 李军. 2023.

- GAO Guang, XIAO Zhi-zhong, MA Wen-hui, PAN Zhao, LI Jun. 2023.

- 软骨鱼类输卵管腺研究进展

- A review of the oviduct glands of cartilaginous fishes

- 海洋科学, 47(9): 141-150

- Marine Sciences, 47(9): 141-150.

- http://dx.doi.org/10.11759/hykx20210825001

-

文章历史

- 收稿日期:2021-08-25

- 修回日期:2021-10-25

2. 青岛海洋科学与技术试点国家实验室 海洋生物学与生物技术功能实验室, 山东 青岛 266237;

3. 中国科学院海洋大科学研究中心, 山东 青岛 266071;

4. 中国科学院大学, 北京 100049;

5. 莱州明波水产有限公司, 山东 烟台 261400;

6. 中国科学院基础医学与肿瘤研究所, 浙江 杭州 310000

2. Pilot National Laboratory for Marine Science and Technology (Qingdao), Qingdao Laboratory for Marine Biology and Biotechnology, Qingdao 266237, China;

3. Center for Ocean Mega-Science, Chinese Academy of Sciences, Qingdao 266071, China;

4. University of Chinese Academy of Sciences, Beijing 100049, China;

5. Laizhou Mingbo Aquatic Co., Ltd, Yantai 261400, China;

6. Institute of Basic Medicine and Cancer, Chinese Academy of Sciences, Hangzhou 310000, China

软骨鱼类作为有颌脊椎动物的重要组成类群[1], 为研究生物演化过程提供了宝贵的研究材料[2]。与硬骨鱼类相比, 软骨鱼类性成熟迟, 繁殖力低, 繁殖周期长, 寿命长, 这使得它们在面对剧烈的环境变化时适应能力较差[3]。另外, 近年来人类生产生活的影响导致全球近七成海洋鲨类和鳐类生存受到严重威胁, 部分种群甚至面临灭绝的风险[4]。然而, 中国软骨鱼类的研究基础仍较薄弱, 目前仅对部分软骨鱼类资源以及繁殖发育等领域进行了研究[5-13]。输卵管腺(oviduct gland)作为雌性软骨鱼类特有的生殖器官, 由输卵管前段发育形成, 参与了卵壳的分泌、受精、排卵等多个关键生命过程, 对于软骨鱼类的繁殖至关重要。然而, 目前国内对输卵管腺的研究仍处于起步阶段。深入研究输卵管腺对于认知海洋生物重要生命过程和软骨鱼类的繁殖保育具有重要意义。

软骨鱼类具有多种多样的生殖方式, 但是不同生殖方式的排卵过程是高度保守的, 发育成熟的卵子从卵巢中脱离后, 在生殖道中完成受精, 并在生殖道分泌物(三级卵膜)的包裹下完成进一步的发育。由于胎生物种的胚胎往往需要与母体建立特殊的营养关系, 因此, 相较于卵生物种, 多数胎生物种的三级卵膜更为轻薄。输卵管腺作为雌性软骨鱼类生殖道前端特化形成的附属生殖器官在此过程当中发挥着重要的功能。该腺体通过其内部各区域腺管精准而协调的分泌形成了软骨鱼类各式各样的三级卵膜。输卵管腺是雌性软骨鱼类形成三级卵膜的核心器官[14]。由于器官的组织结构特点和功能的行使是相适应的, 不同物种的输卵管腺的组织结构往往也会由于其生殖方式不同产生适应性的特化, 但是腺体的分泌过程又是相对保守的[15]。本文从软骨鱼类的生殖方式、不同生殖方式所对应的三级卵膜和输卵管腺结构以及三级卵膜的形成过程等几个方面进行综述。同时, 对该领域研究存在的问题和展望进行了探讨, 旨在为软骨鱼类输卵管腺的相关研究提供参考。

1 软骨鱼类的生殖方式软骨鱼类拥有多样的生殖方式, 主要分为卵生、胎生两类[16]。目前约有40%~43%的软骨鱼类为卵生[17-18], 且卵生物种均为卵黄营养型, 即胚胎发育过程中需要的营养主要来源于卵黄。而其余的软骨鱼类生殖方式为胎生, 其中又可以根据发育过程中母体是否额外供应营养分为: 卵黄营养型胎生(lecithotrophic viviparous)和母源营养型胎生(matrotrophic viviparous)[19-20]。卵黄营养型胎生, 指胚胎发育过程中所需要的营养主要由卵黄所提供, 母体没有额外的营养供应。部分学者也称为“卵胎生(ovoviviparous)”[21]。该类型一般特指卵黄囊胎生(yolk-sac viviparity), 营卵黄囊胎生的物种会将受精卵包裹在一种透明的胶状的卵膜中, 称为蜡鞘(candle)[22-24]。当胚胎发育到一定阶段后会钻破蜡鞘进入到母体子宫中, 在子宫中完成进一步的发育直至产出体外[21]。整个过程中, 卵黄是胚胎的主要营养来源; 母源营养型胎生, 指在胚胎发育过程中母体需要额外对胚胎提供营养以保证发育的顺利进行[25], 根据母体输送养分的形式以及途径又可以将母源营养型胎生划分为组织营养型(histotrophy)[20, 26-27]、互噬型(adelphophagy)[28]、卵噬型(oophagy)[29-30]、胎盘型(placentatrophy)[31-32]。与其他生殖方式不同的是, 营母源营养型胎生的物种, 早期胚胎发育通常在一个薄而折叠的卵膜(egg envelope)中进行。

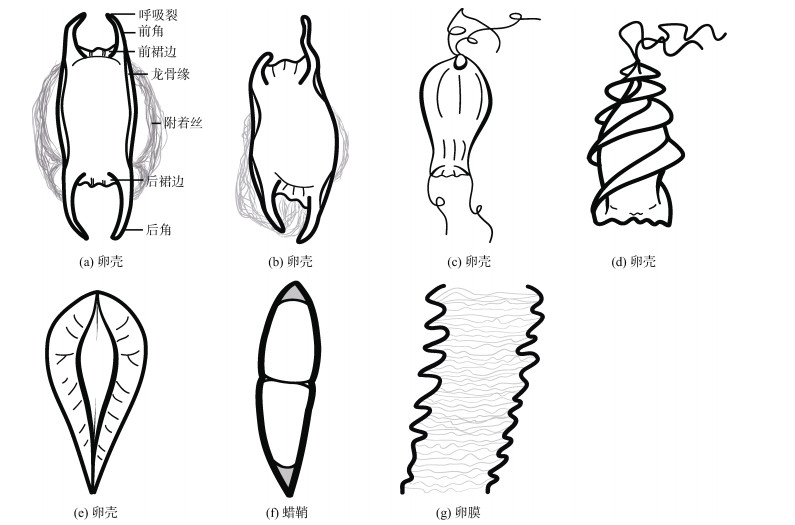

尽管软骨鱼类的生殖方式不尽相同, 但是雌性软骨鱼类的生殖系统结构与功能是相对保守的, 主要由卵巢、输卵管、输卵管腺、子宫等器官组成[33-36]。发育成熟的卵子从卵巢中排出, 经由输卵管进入输卵管腺中, 输卵管腺各部位通过分泌不同的物质对卵子进行进一步的包裹, 最终进入子宫完成进一步的发育或暂存一段时间后直接排出体外。同时值得注意的是, 除了黄点魟(Urobatis jamaicensis)等少部分软骨鱼类不形成三级卵膜外[20], 多数软骨鱼类都会在受精卵外分泌产生三级卵膜以保护胚胎的发育, 根据形态可大致分为三类[15, 20](图 1): 1)质地坚韧的卵壳(egg capsule), 以短尾鳐(Raja brachyura)等卵生软骨鱼类为代表[37-38]; 2)质地柔软的蜡鞘(candle), 以短吻角鲨(Squalus megalops)等卵黄囊胎生型物种为代表[39]; 3)轻薄透光的卵膜(egg envelope), 以黑吻真鲨(Carcharhinus acronotus)等胎盘型胎生鲨鱼为代表[40-41]。虽然形态各不相同, 但是均是由雌性的输卵管腺分泌形成的。

软骨鱼类受精卵的结构相似, 受精卵外包裹着卵胶, 卵胶外有致密的外层。在软骨鱼类输卵管腺所分泌的卵膜中, 卵生软骨鱼类的卵壳种类最为丰富, 同时由于胚胎体外发育, 材料较易获得, 对此类卵壳结构的研究也比其他类卵膜更全面。卵生软骨鱼类卵壳有10种[42], 但根据形态可将卵壳分为布袋型、纺锤型、螺旋型三大类。其中孔鳐(Okamejei kenojei)等[34, 37-38]卵生软骨鱼类的卵壳以布袋型为主(图 1a), 布袋型卵壳整个壳体呈中间鼓的四角布袋型, 卵壳的两侧有结构致密的龙骨缘支撑整个壳体。龙骨缘沿壳体长轴方向分别向上下两个方向延伸形成平行的中空管状结构-角, 同一侧的两个角之间依靠裙边进行平滑连接, 四个角的顶端各有一个呼吸裂, 该结构是海水进入卵壳的入口。在龙骨缘的两侧, 靠近角的基部位置长有附着丝, 具有一定的黏性, 用于缠绕在物体表面。部分种类的布袋型卵壳表现出特殊形态, 例如斑鳍鲨(Parascyllium variolatum)的卵壳呈现左右不对称(图 1b)[43], 斑点猫鲨(Scyliorhinus stellaris)卵壳的角特化形成卷曲附着丝(图 1c)[44]。螺旋型的卵壳以澳大利亚虎鲨(Heterodontus portusjacksoni)等卵生鲨鱼为代表(图 1d)[45], 螺旋型卵壳整个壳体呈梭形, 壳体是由主带和围带构成, 围带从壳体前段呈螺旋状一直延伸到壳体后端, 卵壳末端通常长有附着丝[46]。纺锤形卵壳主要以米氏叶吻银鲛(Callorhinchus milii)等全头亚纲鱼类为主(图 1e)[47], 此类卵壳分为背腹两面, 其中背面较为粗糙, 长有细丝状的毛发, 用于黏附砂石等物质, 腹面较为光滑, 具有吸附作用。其壳体呈中间粗两边细的纺锤形, 壳体两侧的龙骨缘尤为发达, 沿壳体的长轴方向向四周延伸形成侧板, 侧边表面可见脊状隆起。蜡鞘和卵膜的结构较保守, 蜡鞘主要为细长梭形(图 1f), 形似蜡烛, 在蜡鞘两端有卵胶, 但每个蜡鞘中的胚胎数目不同物种有所差异[23, 48-49]; 卵膜主要呈长桶形(图 1g), 有较多褶皱[20]。

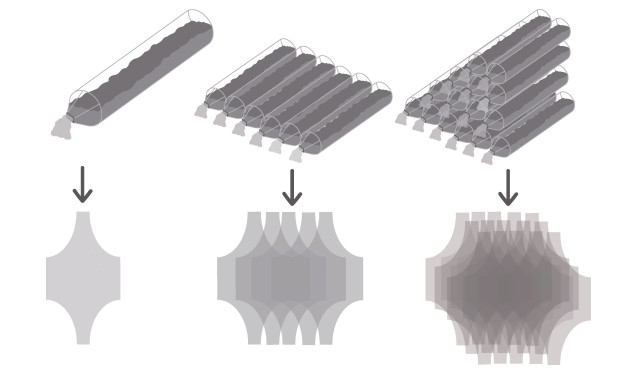

目前, 针对于软骨鱼类的二三级卵膜成分已有较多报道, 各国学者主要通过组织化学染色的方法对卵胶分泌过程进行观察, 一般认为其主要由多糖、糖蛋白等物质组成[50-52]。而卵壳(三级卵膜)的主要成分目前较为明确, 其主要是由高度交联的胶原纤维所构成[53]。以小点猫鲨(Scyliorhinus canicula)为例, 其卵体由约20层胶原蛋白薄片(lamellae)构成, 每层薄片由单层的胶原蛋白带(ribbon)相互堆叠而成, 而每一条胶原蛋白带又是由若干排列规则的胶原纤维(collagen fibrils)构成[20]。

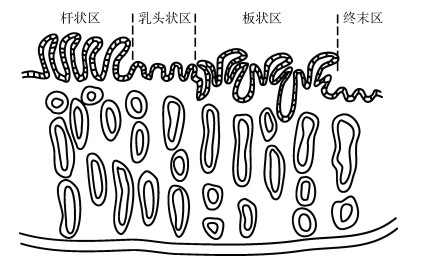

3 输卵管腺的结构软骨鱼类的生殖方式复杂多样, 产生的三级卵膜各不相同, 软骨鱼类的输卵管腺的形态也存在差异[15, 54], 但是在组织学结构和功能上是相对保守的。除花尾燕魟(Gymnura poecilura)部分物种的输卵管腺不形成明显的分区外[55], 多数软骨鱼类的输卵管腺可根据组织学特点分为四个区域(图 2)。靠近输卵管端为前端, 靠近子宫端为后端, 由前至后依次为: 杆状区(club zone)、乳头状区(papillary zone)、板状区(baffle zone)和终末区(terminal zone)[15]。四个区域协调工作, 完成软骨鱼类二三级卵膜的合成与组装[56]。

该区位于输卵管腺的最前端[15], 杆状区的上皮为柱状上皮, 主要由支持细胞和分泌细胞组成, 杆状区上皮向管腔呈柱状的隆起, 该区的固有层有大量的疏松结缔组织和腺管分布。小点猫鲨(Scyliorhinus canicula)的杆状区细胞PAS染色呈阳性, 细胞产物AB和阿辛蓝染色结果呈阳性[57]。棘背鳐(Raja clavata)杆状区的分泌物呈现PAS/AB染色阳性[58]。镜鳐(Raja miraletus)、长吻鳐(Dipturus oxyrinchus)[35]、南极星鲨(Mustelus antarcticus), 杆状区PAS/AB染色结果均呈现阳性[59]。上述组织化学染色结果表明该区的分泌物可能为多糖、黏蛋白类物质。

3.2 乳头状区该区紧靠杆状区, 该区和杆状区参与了卵胶的形成[20], 上皮和腺管细胞组成与杆状区一致, 但上皮的隆起程度变小, 其余结构与杆状区基本一致[15, 56-57], 该区的分泌物可能在卵壳的分泌过程中起润滑作用[20]。

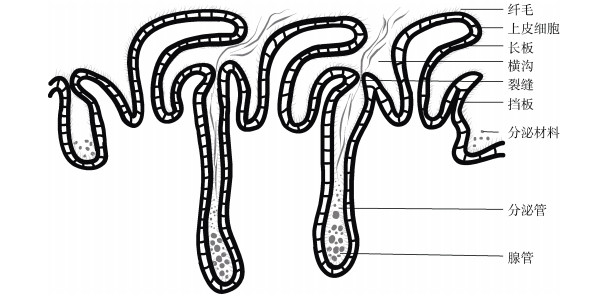

3.3 板状区该区是形成三级卵膜的主要区域, 其上皮向管腔中隆起(图 3), 形成了特殊的形似汉字“山”的板状褶皱, 每一个分泌单位由一对挡板(baffle plate)和一个长板(plateau)构成, 挡板的基部通过分泌管(secretory duct)与腺管(gland tubule)相连, 腺管分泌出的分泌物经由挡板构成的喷丝区(spinneret)后, 通过裂缝进入长板和挡板构成的横沟(transverse groove)中, 分泌物经过横沟的挤压定形后, 排入到管腔, 相邻的横沟之间产生的分泌物相互堆叠在一起形成多层的板状结构, 最终构成卵壳的主体[15]。该区域的组织学特征与卵壳的形态相关, 其中横沟的数量会影响到所合成卵壳的胶原蛋白薄片的层数[20], 横沟的深度则会影响到每层胶原蛋白薄片的厚度[15]。卵壳的螺旋、扭转和延伸等形态学特征, 可能也是腺体中不同部位腺管结构和分泌差异的结果。同时, 通过组织切片技术在某些物种的板状区能够观察到雄性精子的存在[35]。

该区的上皮平滑过渡到子宫, 不再形成褶皱, 但固有层有较多的腺管, 根据其中腺泡的类型可大致分为两类: 浆液性腺管和黏液型腺管。浆液细胞中含有较多的分泌颗粒, 而黏液细胞呈现空泡状, 颗粒较少, 部分物种终末区只有一种腺管[56]。该区域主要参与了卵壳表面毛发的生成以及储存雄性精子等功能[47], 同时该区域特化形成了精子储存结构-储精小管(sperm storage tubule)用于长期储存雄鱼的精子以减少受精过程中对雄性的依赖[60-64]。

4 三级卵膜的形成过程目前相较于胎生软骨鱼类的蜡鞘和卵膜, 卵生软骨鱼类的卵壳研究更为全面, 卵壳的分泌过程可大致分为胞内和胞外两个阶段。以小点猫鲨(Scyliorhinus canicula)的卵壳为例, 卵壳壁中最厚的一层(L2)主要由有序胶原纤维组成。这种胶原蛋白从内质网到分泌颗粒的过程中, 经历了分子排列变化而逐步有序。在细胞内, 胶原蛋白在内质网中呈各向同性, 但进入高尔基体后变为近晶A相或层状相。随着分泌颗粒的成熟, 蛋白会从胶束相和近晶相逐渐过渡到胆甾相, 最终形成六方柱状排列的胶原蛋白。但在胞外分泌时, 胶原迅速变回近晶A相或层状相, 并在经过腺管时, 再次转变并组装成用于形成卵壳的最终有序纤维形式[20, 65-66]。

在胞外, 由于每一根腺管末端开口于由挡板构成的喷丝区结构[15], 两个挡板之间存在一个狭长倾斜的缝隙用于分泌材料的释放和定型, 裂缝大小约为150 nm×10 nm~425 nm×10 nm[67]。分泌材料通过胞吐进入腺管后, 在分泌作用的推动以及纤毛的摆动下, 经过裂缝, 形成宽度厚度一致的胶原蛋白带[15, 20]。同时由于喷丝区结构以瓦片样形式横向地在每个横沟的底部排列成一排, 每条胶原蛋白带相互粘连, 形成了多层板状结构[20, 67], 最终胶原蛋白板从横沟中流出进入到输卵管腺腔参与卵壳的组装。胞外的分泌过程可概括为图 4。此外, 腺管还会继续分泌部分具有特定结构的胶原蛋白对卵壳进一步修饰, 形成毛发等结构[20, 47]。卵生软骨鱼类刚分泌的卵壳颜色较浅, 质地柔软, 通常会在子宫中暂存一段时间, 对卵壳进行硬化以及着色后才排出体外[20]。

|

| 图 4 软骨鱼类卵壳分泌过程模式图 Fig. 4 Schematic drawing of the egg capsule secretion process in cartilaginous fishes |

输卵管腺是软骨鱼类的特有的生殖器官, 部分学者也称之为缠卵腺(nidamental gland)[68-69]、卵壳腺(shell gland)[51], 但是考虑到软骨鱼类产生的三级卵膜具有多样性, 因此使用“输卵管腺(oviduct gland)”一词可能更为准确。

虽然软骨鱼类产生的三级卵膜(卵壳、蜡鞘、卵膜)形态结构各不相同, 但是产生卵膜的过程是相对保守的, 它需要输卵管腺各个区域精确而协调地配合。输卵管腺的分泌过程可能接受雌激素的调控[70], 但是似乎并没有接收来自卵子的相关信号, 因为在饲养过程中经常出现“无黄卵”的现象, 既所产的卵只含有卵壳和卵胶, 不含有卵黄[71], 但针对该现象的原因尚未有系统的研究。同时由于软骨鱼类实验材料的特殊性, 目前输卵管腺的大部分研究主要集中于输卵管腺的组织学、形态学以及内分泌等问题的探讨[72-73], 针对卵膜的分泌与组装过程研究相对较少, 卵壳的显微结构可能与细胞作用等因素有关[20, 74-75], 但造成卵壳形态差异的遗传基础和分子机理, 目前仍存在诸多未知。未来, 结合多组学手段解析软骨鱼类的卵壳分泌过程, 有望为理解这一生命进程提供更多证据。

值得注意的是, 卵生软骨鱼类的生殖方式与鸟类有很多相似之处, 首先两者的生殖系统结构是相似的, 都是由卵巢、输卵管、子宫等几部分构成[76]。发育成熟的卵子从卵巢中排出, 然后在输卵管中完成受精, 最后在输卵管分泌物的包裹下排出体外, 不同的是鸟类的蛋壳是高度钙化的, 而软骨鱼类的主要是由胶原蛋白构成的, 质地较为柔韧。此外, 软骨鱼类卵壳合成时间略早于排卵, 当卵壳合成约2/3时[34], 卵子才进入到卵壳中, 然后输卵管腺完成剩余部分的密封工作后, 将受精卵排入子宫中; 而鸟类的卵壳合成过程是连续的、包裹式的, 卵子进入输卵管后, 形成蛋黄膜、系带蛋清和蛋壳膜等结构, 并伴随有机物沉积; 然后蛋壳腺分泌钙质、色素等物质, 经过矿化后, 最终形成蛋壳[77-78]。除此之外, 软骨鱼类和鸟类雌性生殖系统都具有储存精子的功能, 且在受精过程中二者都存在多精入卵的现象[14, 79]。其中软骨鱼类的精子主要储存于输卵管腺的终末区和挡板区, 受精过程发生在输卵管腺中[69], 鸟类的精子主要储存在子宫和阴道交界处的储精小管里, 受精发生在生殖道的漏斗部, 在此过程中, 孕激素、TGF-β和HSP70等多种物质参与了鸟类精子的储存和释放[76]。而软骨鱼类的体内受精过程还有待进一步研究。

软骨鱼类复杂多样的卵壳以及其独特的分泌过程, 是软骨鱼类繁殖生物学的重要研究内容, 对卵壳分泌现象的深入研究, 有望为新型生物医学材料的开发以及理解海洋生命的演化提供全新的思路, 是一个极具应用价值的研究方向, 同时也是一个涉及生物学、化学、材料学等多领域的交叉学科。但受限于软骨鱼类的生物学特性以及种群资源现状, 目前输卵管腺的相关研究缺乏较为深入的机制机理水平的探索。了解软骨鱼类的资源现状和繁殖规律, 针对不同物种的繁殖特点以及种质资源状况制定相应的人工繁殖保育措施并开发出软骨鱼类生物资源利用技术是未来软骨鱼类研究的重要课题之一。

| [1] |

VENKATESH B, LEE A P, RAVI V, et al. Elephant shark genome provides unique insights into gnathostome evolution[J]. Nature, 2014, 505(7482): 174-179. DOI:10.1038/nature12826 |

| [2] |

RAVI V, LAM K, TAY B H, et al. Elephant shark (Callorhinchus milii) provides insights into the evolution of Hox gene clusters in gnathostomes[J]. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 2009, 106(38): 16327-32. |

| [3] |

赵宇. 台湾海峡南部大吻斜齿鲨Scoliodon macrorhynchos年龄生长与生殖生物学研究[D]. 厦门: 厦门大学, 2018. ZHAO YU. Age, growth and reproductive biology of the Pacific Spadenose shark Scoliodon macrorhynchos from the Southern Taiwan Strait[D]. Xiamen: Xiamen University, 2018. |

| [4] |

PACOUREAU N, RIGBY C L, KYNE P M, et al. Half a century of global decline in oceanic sharks and rays[J]. Nature, 2021, 589(7843): 567-571. DOI:10.1038/s41586-020-03173-9 |

| [5] |

张清榕. 中国海洋软骨鱼类种类分布、资源现状及养护和管理策略探讨[D]. 厦门: 厦门大学, 2007. ZHANG Qingrong. Dicussion on distribution, resource situation, conservation and management plan of chondrichthian fishes in China seas[D]. Xiamen: Xiamen University, 2007. |

| [6] |

于潇. 部分软骨鱼类线粒体基因组特征分析和cox1基因的鉴定应用[D]. 威海: 山东大学, 2017. YU Xiao. Analysis of mitochondrial genome characteristics in some cartilagious fishes and identification of cox1 gene[D]. Weihai: Shandong University, 2017. |

| [7] |

张培玉, 孙淑斌. 山东省沿海软骨鱼的种类与分布[J]. 国土与自然资源研究, 2001(4): 47-48. ZHANG Peiyu, SUN Shubin. The species and distribution of cartilaginous fish in Shandong province coast[J]. Territory & Natural Resources Study, 2001(4): 47-48. DOI:10.3969/j.issn.1003-7853.2001.04.016 |

| [8] |

赵世聪. 中国沿海海域鲸鲨(Rhincodon typus)的分布与遗传多样性研究[D]. 威海: 山东大学, 2016. ZHAO Shicong. Distribution and genetic diversity of Rhincodon typus in coastal waters of China[D]. Weihai: Shandong University, 2016. |

| [9] |

柴爱红. 中国软骨鱼类物种多样性及其利用评估[D]. 天津: 天津科技大学, 2015. CHAI Aihong. Assessments of species diversity and utilization of chondrichthyan fishes in China[D]. Tianjin: Tianjin University of Science and Technology, 2015. |

| [10] |

李宁. 玉筋鱼和赤魟的分子系统地理学研究[D]. 青岛: 中国海洋大学, 2014. LI Ning. Molecular phylogeography of sand lance and the red stingray in the Northwest[D]. Qingdao: Ocean University of China, 2014. |

| [11] |

申欣, 田美, 孟学平, 等. 10种软骨鱼线粒体基因组特征分析[J]. 渔业科学进展, 2011, 32(3): 26-32. SHEN Xin, TIAN Mei, MENG Xueping, et al. Analysis of the characteristics of ten cartilaginous fishes mitochondrial genomes[J]. Progress in Fishery Sciences, 2011, 32(3): 26-32. |

| [12] |

蒋新花. 福建沿岸海域软骨鱼类资源及其系统进化研究[D]. 厦门: 集美大学, 2010. JIANG Xinhua. Study on the resources and plylogenetic evolution of cartilagious fishes in Fujian coastal waters[D]. Xiamen: Jimei University, 2010. |

| [13] |

刘丽华. 闽南近海条纹斑竹鲨(Chiloscyllium plagiosum Bennett, 1830)脂肪酸的研究[D]. 厦门: 厦门大学, 2006. LIU Lihua. Studies on fatty acid of white-spotted bamboo shark, Chiloscyllium plagiosum (Bennett, 1830), from southern Fujian coastal waters[D]. Xiamen: Xiamen University, 2006. |

| [14] |

WOURMS J P. Reproduction and development in chondrichthyan fishes[J]. American Zoologist, 1977, 17(2): 379-410. DOI:10.1093/icb/17.2.379 |

| [15] |

HAMLETT W C, KNIGHT D P, KOOB T J, et al. Survey of oviducal gland structure and function in elasmobranchs[J]. Journal of Experimental Zoology, 1998, 282(4/5): 399-420. |

| [16] |

TESHIMA K, MIZUE K. Studies on sharks. I. Reproduction in the female sumitsuki shark Carcharhinus dussumieri[J]. Marine Biology, 1972, 14(3): 222-231. DOI:10.1007/BF00348283 |

| [17] |

COMPAGNO L J V. Alternative life-history styles of cartilaginous fishes in time and space[J]. Environmental Biology of Fishes, 1990, 28(1/4): 33-75. |

| [18] |

DULVY N K, REYNOLDS J D. Evolutionary transitions among egg-laying, live-bearing and maternal inputs in sharks and rays[J]. Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences, 1997, 264(1386): 1309-1315. DOI:10.1098/rspb.1997.0181 |

| [19] |

SHADWICK R E, FARRELL A P, BRAUNER C J. Physiology of Elasmobranch Fishes: Structure and Interaction with Environment[M]. Amsterdam: Elsevier Ltd, 2016: 255-295.

|

| [20] |

HAMLETT W C. Reproductive Biology and Phylogeny of Chondrichthyes: Sharks, Batoids and Chimaeras[M]. Enfield: Science Publishers Inc, 2005: 287-396.

|

| [21] |

EVANS D H, OIKARI A, KORMANIK G A, et al. Osmoregulation by the prenatal spiny dogfish, Squalus Acanthias[J]. Journal of Experimental Biology, 1982, 101(1): 295-305. DOI:10.1242/jeb.101.1.295 |

| [22] |

PRICE JR K S, DAIBER F C. Osmotic environments during fetal development of dogfish, Mustelus canis (Mitchill) and Squalus acanthias Linnaeus, and some comparisons with skates and rays[J]. Physiological Zoology, 1967, 40(3): 248-260. DOI:10.1086/physzool.40.3.30152862 |

| [23] |

SUNYE P S, VOOREN C M. On cloacal gestation in angel sharks from southern Brazil[J]. Journal of Fish Biology, 1997, 50(1): 86-94. DOI:10.1111/j.1095-8649.1997.tb01341.x |

| [24] |

NAMMACK M F, MUSICK J A, COLVOCORESSES J A. Life history of spiny dogfish off the Northeastern United States[J]. Transactions of the American Fisheries Society, 1985, 114(3): 367-376. DOI:10.1577/1548-8659(1985)114<367:LHOSDO>2.0.CO;2 |

| [25] |

WOURMS J P. Viviparity: The maternal-fetal relationship in fishes[J]. American Zoologist, 1981, 21(2): 473-515. DOI:10.1093/icb/21.2.473 |

| [26] |

STORRIE M T, WALKER T I, LAURENSON L J, et al. Gestational morphogenesis of the uterine epithelium of the gummy shark (Mustelus antarcticus)[J]. Journal of Morphology, 2010, 270(3): 319-336. |

| [27] |

WHITE W T, PLATELL M E, POTTER I C. Relationship between reproductive biology and age composition and growth in Urolophus lobatus (Batoidea: Urolophidae)[J]. Marine Biology, 2001, 138: 135-47. DOI:10.1007/s002270000436 |

| [28] |

GILMORE R G, DODRILL J W, LINLEY P A. Reproduction and embryonic-development of the sand tiger shark, Odontaspis taurus (Rafinesque)[J]. Fishery Bulletin, 1983, 81(2): 201-225. |

| [29] |

YANO K. Comments on the reproductive mode of the false cat shark Pseudotriakis microdon[J]. Copeia, 1992(2): 460-468. |

| [30] |

YANO K. Reproductive biology of the slender smoothhound, Gollum attenuatus, collected from New Zealand waters[J]. Environmental Biology of Fishes, 1993, 38(1/3): 59-71. |

| [31] |

LóPEZ J A, RYBURN J A, FEDRIGO O, et al. Phylogeny of sharks of the family Triakidae (Carcharhiniformes) and its implications for the evolution of carcharhiniform placental viviparity[J]. Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution, 2006, 40(1): 50-60. DOI:10.1016/j.ympev.2006.02.011 |

| [32] |

BUDDLE A L, VAN DYKE J U, THOMPSON M B. Structure of the paraplacenta and the yolk sac placenta of the viviparous Australian sharpnose shark, Rhizoprionodon taylori[J]. Placenta, 2021, 108(1): 11-22. |

| [33] |

胡灯进. 闽南近海条纹斑竹鲨(Chiloscyllium plagiosum Bennett)年龄生长和生殖生物学研究[D]. 厦门: 厦门大学, 2005. HU Dengjin. Study on age, growth and reproductive biology of Chiloscyllium plagiosum from southern coast of Fujian[D]. Xiamen: Xiamen University, 2005. |

| [34] |

阎淑珍. 孔鳐卵壳形成及其排卵的初步观察[J]. 海洋与湖沼, 1978, 9(2): 236-240, 246. YAN Shuzhen. Primary observation on the ovulation and egg capsule formation of skates[J]. Oceanologia et Limnologia Sinica, 1978, 9(2): 236-240, 246. |

| [35] |

MARONGIU M F, PORCU C, BELLODI A, et al. Oviducal gland microstructure of Raja miraletus and Dipturus oxyrinchus (Elasmobranchii, Rajidae)[J]. Journal of Morphology, 2015, 276(11): 1392-403. DOI:10.1002/jmor.20426 |

| [36] |

WEHITT A, DI GIACOMO E E, GALíNDEZ E J. The female reproductive system of Zearaja chilensis (Guichenot, 1848)(Chondrichthyes, Rajidae): gametogenesis and microscopic validation of maturity criteria[J]. International Journal of Morphology, 2015, 33(1): 309-317. DOI:10.4067/S0717-95022015000100049 |

| [37] |

CLARK R S. Rays and skates (Raiœ) No. 1. —egg-capsules and young[J]. Journal of the Marine Biological Association of the United Kingdom, 1922, 12(4): 578-643. DOI:10.1017/S002531540000967X |

| [38] |

TRELOAR M A, LAURENSON L J B, STEVENS J D. Descriptions of rajid egg cases from southeastern Australian waters[J]. Zootaxa, 2006, 1231: 53-68. DOI:10.11646/zootaxa.1231.1.3 |

| [39] |

BRACCINI J M, HAMLETT W C, GILLANDERS B M, et al. Embryo development and maternal–embryo nutritional relationships of piked spurdog (Squalus megalops)[J]. Marine Biology, 2007, 150: 727-737. |

| [40] |

BUDDLE A L, VAN DYKE J U, THOMPSON M B, et al. Evolution of placentotrophy: using viviparous sharks as a model to understand vertebrate placental evolution[J]. Marine and Freshwater Research, 2019, 70(7): 908-924. DOI:10.1071/MF18076 |

| [41] |

HAMLETT W C, EULITT A M, JARRELL R L, et al. Uterogestation and placentation in elasmobranchs[J]. Journal of Experimental Zoology, 1993, 266(5): 347-67. DOI:10.1002/jez.1402660504 |

| [42] |

FISCHER J, LICHT M, KRIWET J, et al. Egg capsule morphology provides new information about the interrelationships of chondrichthyan fishes[J]. Journal of Systematic Palaeontology, 2014, 12(3): 389-399. DOI:10.1080/14772019.2012.762061 |

| [43] |

CARUSO J, BOR P H F. Egg capsule morphology of Parascyllium variolatum (Dumeril, 1853) (Chondrichthyes; Parascylliidae), with notes on oviposition rate in captivity[J]. Journal of Fish Biology, 2007, 70(5): 1620-1625. DOI:10.1111/j.1095-8649.2007.01431.x |

| [44] |

MUSA S M, CZACHUR M V, SHIELS H A. Oviparous elasmobranch development inside the egg case in 7 key stages[J]. PLoS One, 2018, 13(11): e0206984. DOI:10.1371/journal.pone.0206984 |

| [45] |

RODDA K R, SEYMOUR R S. Functional morphology of embryonic development in the Port Jackson shark Heterodontus portusjacksoni (Meyer)[J]. Journal of Fish Biology, 2008, 72(4): 961-984. DOI:10.1111/j.1095-8649.2007.01777.x |

| [46] |

FISCHER J, VOIGT S, SCHNEIDER J W, et al. A selachian freshwater fauna from the Triassic of Kyrgyzstan and its implication for Mesozoic shark nurseries[J]. Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology, 2011, 31(5): 937-953. DOI:10.1080/02724634.2011.601729 |

| [47] |

SMITH R M, WALKER T I, HAMLETT W C. Microscopic organisation of the oviducal gland of the holocephalan elephant fish, Callorhynchus milii[J]. Marine and Freshwater Research, 2004, 55(2): 155-164. DOI:10.1071/MF01078 |

| [48] |

KORMANIK G A. Ionic and osmotic environment of developing elasmobranch embryos[J]. Environmental Biology of Fishes, 1993, 38(1/3): 233-240. |

| [49] |

MCLAUGHLIN D M, MORRISSEY J F. Reproductive biology of Centrophorus cf. uyato from the Cayman Trench, Jamaica[J]. Journal of the Marine Biological Association of the United Kingdom, 2005, 85(5): 1185-1192. DOI:10.1017/S0025315405012282 |

| [50] |

SOMSAP N, SRAKAEW N, CHATCHAVALVANICH K. Microanatomy of the female reproductive system of the viviparous freshwater whipray Fluvitrygon signifer (Chondrichthyes: Myliobatiformes: Dasyatidae). Ⅱ. The genital duct[J]. BMC Zoology, 2021, 6(1): 1-18. DOI:10.1186/s40850-021-00065-x |

| [51] |

RUSAOUËN M. The dogfish shell gland, a histochemical study[J]. Journal of Experimental Marine Biology and Ecology, 1976, 23(3): 267-283. DOI:10.1016/0022-0981(76)90025-3 |

| [52] |

HAMLETT W C, FISHELSON L, BARANES A, et al. Ultrastructural analysis of sperm storage and morphology of the oviducal gland in the Oman shark, Iago omanensis (Triakidae)[J]. Marine and Freshwater Research, 2002, 53(2): 601-613. DOI:10.1071/MF01080 |

| [53] |

ICONOMIDOU V A, GEORGAKA M E, CHRYSSIKOS G D, et al. Dogfish egg case structural studies by ATR FT-IR and FT-Raman spectroscopy[J]. International Journal of Biological Macromolecules, 2007, 41(1): 102-108. DOI:10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2007.01.002 |

| [54] |

NALINI M K P. Structure and function of the nidamental gland of Chiloscyllium griseum(Mull. and Henle) [C]. Proceedings Indian Academy of Sciences. New Delhi: Springer India, 1940, 12(5): 189-214.

|

| [55] |

HENDERSON A C, REEVE A J, AMBU-ALI A. Microanatomy of the male and female reproductive tracts in the long-tailed butterfly ray Gymnura poecilura, an elasmobranch with unusual characteristics[J]. Journal of Fish Biology, 2014, 84(2): 297-313. DOI:10.1111/jfb.12282 |

| [56] |

MAIA C, SERRA-PEREIRA B, ERZINI K, et al. How is the morphology of the oviducal gland and of the resulting egg capsule associated with the egg laying habitats of Rajidae species?[J]. Environmental Biology of Fishes, 2015, 98(10): 2037-2048. DOI:10.1007/s10641-015-0425-1 |

| [57] |

THREADGOLD L T. A histochemical study of the shell gland of Scyliorhinus caniculus[J]. Journal of Histochemistry & Cytochemistry, 1957, 5(2): 159-166. |

| [58] |

SERRA-PEREIRA B, AFONSO F, FARIAS I, et al. The development of the oviducal gland in the Rajid thornback ray, Raja clavata[J]. Helgoland Marine Research, 2011, 65(3): 399-411. DOI:10.1007/s10152-010-0232-1 |

| [59] |

STORRIE M T, WALKER T I, LAURENSON L J, et al. Microscopic organization of the sperm storage tubules in the oviducal gland of the female gummy shark (Mustelus antarcticus), with observations on sperm distribution and storage[J]. Journal of Morphology, 2008, 269(11): 1308-1324. DOI:10.1002/jmor.10646 |

| [60] |

PORCU C, MARONGIU M F, FOLLESA M C, et al. Reproductive aspects of the velvet belly Etmopterus spinax (Chondrichthyes: Etmopteridae), from the central western Mediterranean Sea. Notes on gametogenesis and oviducal gland microstructure[J]. Mediterranean Marine Science, 2014, 15(2): 313-326. |

| [61] |

PRATT H L. The storage of spermatozoa in the oviducal glands of western North Atlantic sharks[J]. Environmental Biology of Fishes, 1993, 38(1/3): 139-149. |

| [62] |

FISHELSON L, BARANES A. Observations on the Oman shark, Iago omanensis (Triakidae), with emphasis on the morphological and cytological changes of the oviduct and yolk sac during gestation[J]. Journal of Morphology, 1998, 236(3): 151-165. DOI:10.1002/(SICI)1097-4687(199806)236:3<151::AID-JMOR1>3.0.CO;2-6 |

| [63] |

ELÍAS F G. Histochemical study of the oviducal gland and analysis of the sperm storage tubules of Mustelus schmitti Springer, 1939 (Chondrichthyes, Triakidae)[J]. Pesquisa Veterinaria Brasileira, 2015, 35(8): 741-748. DOI:10.1590/S0100-736X2015000800006 |

| [64] |

MOURA T, SERRA‐PEREIRA B, GORDO L S, et al. Sperm storage in males and females of the deepwater shark Portuguese dogfish with notes on oviducal gland microscopic organization[J]. Journal of Zoology, 2011, 283(3): 210-219. DOI:10.1111/j.1469-7998.2010.00775.x |

| [65] |

KNIGHT D P, HU X W, GATHERCOLE L J, et al. Molecular orientations in an extruded collagenous composite, the marginal rib of the egg capsule of the dogfish Scyliorhinus canicula; A novel lyotropic liquid crystalline arrangement and its origin in the spinnerets[J]. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London. Series B: Biological Sciences, 1996, 351(1344): 1205-1222. DOI:10.1098/rstb.1996.0103 |

| [66] |

KNIGHT D P, FENG D, STEWART M, et al. Changes in macromolecular organization in collagen assemblies during secretion in the nidamental gland and formation of the egg capsule wall in the dogfish Scyliorhinus canicula[J]. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London. Series B: Biological Sciences, 1993, 341(1298): 419-436. DOI:10.1098/rstb.1993.0125 |

| [67] |

KNIGHT D P, VOLLRATH F. Comparison of the spinning of Selachian egg case ply sheets and orb web spider dragline filaments[J]. Biomacromolecules, 2001, 2(2): 323-334. DOI:10.1021/bm0001446 |

| [68] |

BARANES A, WENDLING J. The early stages of development in Carcharhinus plumbeus[J]. Journal of Fish Biology, 1981, 18(2): 159-175. DOI:10.1111/j.1095-8649.1981.tb02811.x |

| [69] |

LECHENAULT H, MELLINGER J. Dual origin of yolk nuclei in the lesser spotted dogfish, Scyliorhinus canicula (chondrichthyes)[J]. Journal of Experimental Zoology, 1993, 265(6): 669-678. DOI:10.1002/jez.1402650609 |

| [70] |

DODD J M, GODDARD C K. Some effects of oestradiol benzoate on the reproductive ducts of the female dogfish Scyliorhinus caniculus[C]. Proceedings of the Zoological Society of London. Oxford, UK: Blackwell Publishing Ltd, 1961, 137(3): 325-331.

|

| [71] |

KOOP J H. Reproduction of captive Raja spp. in the Dolfinarium Harderwijk[J]. Journal of The Marine Biological Association of The United Kingdom, 2005, 85(5): 1201-1202. DOI:10.1017/S0025315405012312 |

| [72] |

KOOB T J, TSANG P, CALLARD I P. Plasma estradiol, testosterone, and progesterone levels during the ovulatory cycle of the skate (Raja erinacea)[J]. Biology of Reproduction, 1986, 35(2): 267-275. DOI:10.1095/biolreprod35.2.267 |

| [73] |

MOYA A C, ACUNA F, DÍAZ ANDRADE M C, et al. Glycan expression as a tool for a deeper understanding of a reproductive gland in a skate of economic importance[J]. Journal of Fish Biology, 2021, 98(2): 537-547. DOI:10.1111/jfb.14597 |

| [74] |

KNIGHT D P, FENG D. Some observations on the collagen fibrils of the egg capsule of the dogfish, Scyliorhinus canicula[J]. Tissue and Cell, 1994, 26(3): 385-401. DOI:10.1016/0040-8166(94)90022-1 |

| [75] |

GOBEAUX F, BELAMIE E, MOSSER G, et al. Cooperative ordering of collagen triple helices in the dense state[J]. Langmuir, 2007, 23(11): 6411-6417. DOI:10.1021/la070093z |

| [76] |

HOLT W V, FAZELI A. Sperm storage in the female reproductive tract[J]. Annual Review of Animal Biosciences, 2016, 4: 291-310. DOI:10.1146/annurev-animal-021815-111350 |

| [77] |

沈涛涛, 张佳兰, 吴艳, 等. 蛋壳形成及其调控机制的研究进展[J]. 中国畜牧杂志, 2021, 57(6): 31-36. SHEN Taotao, ZHANG Jialan, WU Yan, et al. Research progress on eggshell formation and its regulation mechanism[J]. Chinese Journal of Animal Science, 2021, 57(6): 31-36. |

| [78] |

张权. 鸡OC17基因克隆、表达及其Ser61位点对碳酸钙结晶功能研究[D]. 北京: 中国农业大学, 2015. ZHANG Quan. Cloning and expression of OC17 gene in chicken and Ser61 function for calcium carbonate crystallization[D]. Beijing: China Agricultural University, 2015. |

| [79] |

HEMMINGS N, BIRKHEAD T R. Polyspermy in birds: sperm numbers and embryo survival[J]. Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences, 2015, 282(1818): 20151682. DOI:10.1098/rspb.2015.1682 |

2023, Vol. 47

2023, Vol. 47