中国海洋湖沼学会主办。

文章信息

- 刘敏, 车文学, 边伟杰, 甘禧霖, 赵怀宝. 2022.

- LIU Min, CHE Wen-Xue, BIAN Wei-Jie, GAN Xi-Lin, ZHAO Huai-Bao. 2022.

- 八门湾红树林土壤放线菌多样性及抗病原菌活性分析

- DIVERSITY AND ANTIMICROBIAL ACTIVITY OF ACTINOBACTERIA IN THE SOIL OF THE BAMENWAN MANGROVE IN HAINAN, CHINA

- 海洋与湖沼, 53(2): 352-363

- Oceanologia et Limnologia Sinica, 53(2): 352-363.

- http://dx.doi.org/10.11693/hyhz20210800176

文章历史

-

收稿日期:2021-08-04

收修改稿日期:2021-09-12

红树林生态系统是指位于热带和亚热带海岸潮间带, 包括种类丰富的动物群落、红树木本植物群落、微生物群落的复杂而独特的生态系统。红树林生态系统覆盖了世界上60%~75%的海岸线, 是生产力水平最高的四个海洋生态系统之一(Alongi, 2008)。红树林作为重要的近岸湿地生态系统, 具有防风消浪、促淤护岸、调节大气、净化海水和美化景观等作用, 对海洋环境保护和生态平衡有重要的作用(Alongi, 2008)。红树林土壤具有高湿度、高盐度、强还原性、强酸性、营养成分丰富等特点, 因此微生物群落具有极高的多样性和独特性(Alongi, 1996)。

放线菌广泛分布于陆地(Hayakawa et al, 2000; Xu et al, 2014)和海洋生境(Demain et al, 2009; 洪葵, 2013)。由于红树林生态环境的独特性, 被认为是分离放线菌新种资源的理想生境(Ser et al, 2016b; Huang et al, 2018; 候师师等, 2020; Asha et al, 2021)。已有研究表明红树林土壤中存在丰富多样的放线菌资源(洪葵, 2013; Claverías et al, 2015), 部分菌株已被鉴定为新种(Demain et al, 2009; Suthindhiran et al, 2010; Arumugam et al, 2017; Huang et al, 2018)。放线菌因其具有产生多种生物活性次级代谢产物的能力而备受关注(Demain et al, 2009), 具有多种抗菌、抗氧化、抗癌、神经保护和酶抑制剂等功能(Amrita et al, 2012; Ser et al, 2016b; Arumugam et al, 2017), 在医药、工业、农业、生态等领域有广泛应用(Xu et al, 2014)。然而, 近年来从陆地来源的放线菌中发现活性化合物效率低(Ser et al, 2016b), 因此, 从海洋生境中寻找新的放线菌资源及其天然产物越来越受到关注, 其中红树林已成为寻找新的放线菌资源及其天然产物的热点生境。

为了挖掘出更多新的放线菌菌株以满足活性物质开发, 首先需要了解它们的多样性。以往的研究主要集中于传统培养方法对红树林放线菌多样性的研究(Mevs et al, 2000; Janssen et al, 2002; Page et al, 2004; Arumugam et al, 2017; Law et al, 2017; Huang et al, 2018)。本研究将利用两种不同引物(放线菌相关引物和细菌通用引物)对八门湾红树林土壤放线菌在非培养水平多样性进行对比分析; 利用传统培养法对红树林土壤放线菌在可培养水平多样性进行分析, 同时分析放线菌的抗病原菌活性, 为后续从红树林生境中挖掘新的放线菌资源提供前期数据支持, 也为放线菌的开发利用提供菌种资源。

1 材料与方法 1.1 样品采集样品采集地点位于海南省文昌市八门湾红树林湿地, 以Bruguiera sexangular和Xylocarpus mekongensis为优势树种的红树林区, 设立3个采样点, 于2011年12月采集5~30 cm深的黑褐色泥质土壤样品, 在每个采样点采集3份重复土壤样品(每份约500 g土壤), 重复样品采集点呈正三角形分布(两点间隔5 m), 然后将三个重复样品混匀, 将所有样品混合均匀, 置于冰盒带回实验室, 用于后续实验。

1.2 DNA提取和高通量测序土壤总DNA的提取按照试剂盒FastPrep® SPIN Kit for Soil (MP Biomedicals, 美国)步骤进行。利用两对引物对16S rDNA进行扩增, 引物分别是: 放线菌相关引物(可提高环境样品中放线菌的检出率)ACT235F (CGCGGCCTATCAGCTTGTTG)和ACT878R (CCGTACTCCCCAGGCGGGG), 细菌通用引物341F (5′-CCTACGGGAGGCAGCAG-3′)和1073R (5′-ACGAGCTGACGACARCCATG-3′) (Farris et al, 2007)。PCR反应体系为(20 μL混合体系): 4 μL 5× FastPfu Buffer, 2 μL 2.5 mmol/L dNTPs, 0.8 μL引物1 (5 μmol/L), 0.8 μL引物2 (5 μmol/L), 0.4 μL FastPfu Polymerase, 10 ng模板DNA。PCR反应程序: 95 ℃ 10 min; 95 ℃ 30 s, 55 ℃ 30 s, 72 ℃ 30 s; 72 ℃ 10 min (Liu et al, 2017)。利用AxyPrep DNA Gel Extraction Kit (Axygen Biosciences, 美国)胶回收试剂盒对PCR产物纯化, 利用QuantiFluorTM -ST (Promega, 美国)进行定量, 然后送至上海美吉医药科技有限公司进行高通量测序(Roche Genome Sequencer GS FLX+ Titanium platform)。对获得的原始序列进行拼接、过滤除杂和去除嵌合体等质量控制后得到最终分析的有效序列, 通过UPARSE (version 7.1 http://drive5.com/uparse/)对有效序列以97%的一致性进行聚类分析, 获得OTU (操作分类单元, operational taxonomic unit)(Yan et al, 2006; Dias et al, 2011)。将OTU序列与SILVA数据库进行比对确定OTU的系统发育信息(Yan et al, 2006; Dias et al, 2011; Mendes et al, 2012), 使用QIIME(版本1.17)处理序列(Caporaso et al, 2010), 进行多样性和群落结构分析。将从高通量测序数据中选取放线菌门序列做进一步分析。高通量测序序列在NCBI数据库的序列接收号为SRX506963和SRX3938853。

1.3 放线菌的分离和16S rDNA序列分析土壤在室温下自然风干, 然后研磨成粉末。沉淀物粉末采用以下两种方法处理: 一种方法是将5 g沉淀物粉末悬浮在10 mL林格氏液中, 并将水加热至55 ℃; 另一种方法是将5 g沉淀物粉末在120 ℃下加热1 h, 然后悬浮在10 mL林格氏液中。将沉淀物悬浮液在28 ℃摇床(180 r/min转速)摇动30 min。利用稀释涂布平板法, 将稀释(10−2到10−4)的土壤悬浮液涂布在琼脂分离培养基上分离放线菌菌株。分离培养基有: 高氏合成一号培养基(20 g可溶性淀粉, 1 g KNO3, 0.5 g K2HPO4, 0.5 g MgSO4·7H2O, 0.1 g FeSO4·7H2O, 15 g琼脂, 1 L海水, pH 7.2); 腐殖酸维生素培养基(1.0 g腐殖酸, 0.5 g Na2HPO4, 1.7 g KCL, 21 g CaCL2, 0.5 g MgSO4·7H2O, 0.01 g FeSO4·H2O, 复合维生素, H2O 1 L, 20.0 g琼脂, pH 7.2; 复合维生素: 0.5 mg肌醇, 0.5 mg泛酸, 0.5 g氨基苯酸, 0.25 mg生物素, 0.5 mg VB1, 0.5 mg VB2, 0.5 mg VB3, 0.5 mg VB6); 土壤提取物培养基(50%土壤提取物, 2%琼脂, 1 L海水, pH 6.8)。在分离培养基中, 添加细菌与真菌抑制剂: 50 µg/mL重铬酸钾、100 µg/mL制霉菌素、20 µg/mL萘啶酮酸。将平板置于28 ℃恒温培养箱中倒置培养2~4周, 挑取符合条件的单菌落划线于ISP2培养基上直至菌株纯化。纯化菌株的16S rDNA序列使用细菌通用引物PCR扩增, 引物为27f (5′-AGAGTTTGAT CMTGCCTCAG-3′)和1492r (5′-TACGGYTACCTTG TTACGACTT-3′), 16S rDNA序列提交至EzBioCloud (http://www.ezbiocloud.net/)进行系统发育相似性比对。多样性分析采用Shannon-Wiener多样性指数:

其中Pi=Ni/N即第i种占总个体数N的比例。

1.4 抗病原菌活性测定为了分析抗菌活性, 菌株在ISP2培养基中28 ℃摇床(200 r/min)培养, 7~14 d后, 收集发酵液并离心, 取上清液通过0.45 µm和0.2 µm硝酸纤维素过滤器过滤, 然后使用纸片扩散法测定抗菌活性(Kamei et al, 2003)。试验中使用的致病微生物菌株为Colletotrichum gloeosporioides、Escherichia coli、Fusarium oxysporum、Staphylococcus aureus和Vibrio neocaledonicus。

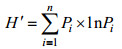

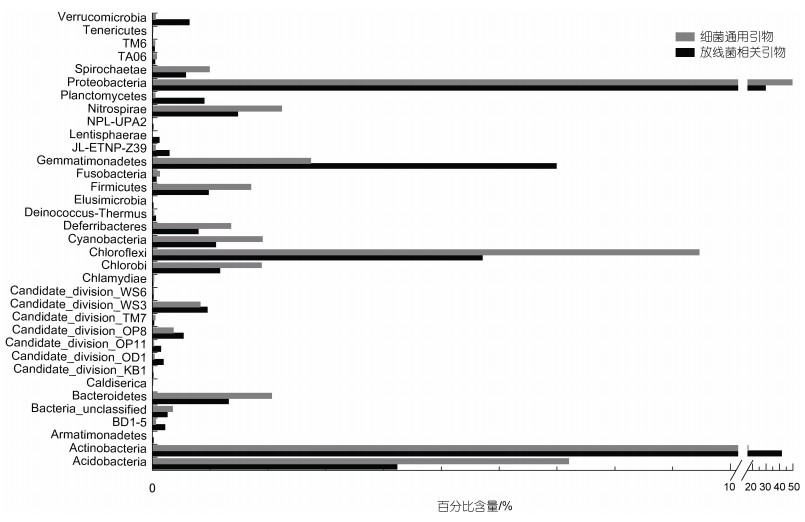

2 结果与讨论 2.1 在非培养水平上放线菌多样性分析利用放线菌相关引物进行扩增子高通量测序, 经过质控检测后, 共获得44 003条有效序列用来进一步分析, 测序深度指数Good’s coverage为0.986 6~0.989 6, 表明测序量足够大, 可以反映样品中绝大部分的微生物物种信息(附表1)。对于细菌群落多样性, 共检测到33个门, 前10个门分别是: Actinobacteria (41.56%)、Proteobacteria (29.48%)、Gemmatimonadetes (6.99%)、Chloroflexi (5.71%)、Acidobacteria (4.23%)、Nitrospirae (1.48%)、Bacteroidetes (1.31%)、Chlorobi (1.17%)、Cyanobacteria (1.10%)和Firmicutes (0.97%) (图 1)。对于放线菌多样性, 共有18297条序列属于Actinobacteria门, 共包括15个目, 分别是: Acidimicrobiales (30.10%)、Corynebacteriales (17.25%)、Gaiellales (9.90%)、Kineosporiales (9.82%)、Solirubrobacterales (6.70%)、Frankiales (5.57%)、Micrococcales (5.11%)、Micromonosporales (4.60%)、Propionibacteriales (3.12%)、Streptomycetales (1.26%)、Pseudonocardiales (0.99%)、PeM15 (0.35%)、Streptosporangiales (0.27%)、Euzebyales (0.11%)、Coriobacteriales (0.05%)和未分类放线菌(4.80%) (图 2); 29个科(不包括未培养和未分类的科), 32个属, 其中百分比大于1%的属包括Mycobacterium (16.2%)、Acidothermus (4.9%)、Ilumatobacter (2.3%)、Gaiella (1.5%)、Quadrisphaera (1.7%)、Microbacterium (1.7%)、Intrasporangium (1.3%)、Luedemannella (1.5%)、Nocardioides (1.4%)和Streptomyces (1.3%) (附表2)。

|

| 图 1 利用放线菌相关引物和细菌通用引物对八门湾红树林土壤细菌多样性的分析(门水平) Fig. 1 Diversity of bacteria in the phylum level from soil of Bamenwan mangrove by pyrosequencing methods with Actinobacteria-specific primer and the universal bacterial primer |

|

| 图 2 利用放线菌相关引物和细菌通用引物对八门湾红树林土壤放线菌多样性的分析(目水平) Fig. 2 Diversity of Actinobacteria in the order level from soil of Bamenwan mangrove by pyrosequencing with Actinobacteria-specific primer and the universal bacterial primer |

利用细菌通用引物进行扩增子高通量测序, 经过质控检测, 共有24 821条有效序列用来进一步分析, 测序深度指数Good’s coverage为0.979 4~0.989 0, 表明测序量足够大, 可以反映样品中绝大部分的微生物物种信息(附表1)。对于细菌群落多样性, 共检测到30个门, 其中前10个门分别是: Proteobacteria (49.40%)、Actinobacteria (16.79%)、Chloroflexi (9.46%)、Acidobacteria (7.20%)、Gemmatimonadetes (2.74%)、Nitrospirae (2.24%)、Bacteroidetes (2.06%)、Cyanobacteria (1.90%)、Chlorobi (1.89%)、Firmicutes (1.71%)(Fig. 1)。对于放线菌多样性, 共有4140条序列属于Actinobacteria门, 共包括13个目, 分别是: Gaiellales (28.03%)、Acidimicrobiales (27.57%)、Solirubrobacterales (22.82%)、Kineosporiales (7.10%)、Micrococcales (2.73%)、Frankiales (2.51%)、Propionibacteriales (1.11%)、Corynebacteriales (0.94%)、Micromonosporales (0.94%)、Streptomycetales (0.51%)、PeM15 (0.27%)、Coriobacteriales (0.22%)、Euzebyales (0.17%)、Streptosporangiales (0.10%)、未分类放线菌(4.97%) (图 2); 23个科(不包括未培养和未分类的科)(附表2); 17个属, 其中百分比大于1%的属包括Gaiella (6.43%)、Kineosporia (3.31%)、Acidothermus (2.10%)和Ilumatobacter (1.62%) (附表2)。

通过对放线菌相关引物和细菌通用引物获得的数据对比分析可知: (1) 与细菌通用引物相比, 利用放线菌相关引物可以检测到更多的目、科和属; (2) 对于在门水平上的细菌群落组成来说, Actinobacteria、Proteobacteria、Gemmatimonadetes、Chloroflexi、Acidobacteria都是优势类群, 但是其百分含量差异较大; 利用放线菌相关引物可以提高Actinobacteria丰度的检测水平, 其百分比含量提高了2.47倍; Gemmatimonadetes的百分比含量提高2.55倍; 此外, 对于minor-groups(所占百分比小于1%的类群)中Planctomycetes和Verrucomicrobia检出丰度也分别提高18和11倍; 其中三个minor-groups (Lentisphaerae、Elusimicrobia和Armatimonadetes)只在利用放线菌相关引物进行测序时检测到(图 1); (3) 对于在目水平上的放线菌类群组成来说, 5个目(Acidimicrobiales、Corynebacteriales、Gaiellales、Kineosporiales、Solirubrobacterales)是丰度相对较高的类群, 在两对不同引物得到的结果中, 其丰度差异较大; 利用放线菌相关引物检出的Corynebacteriales的百分含量提高了18.32倍, Micromonosporales提高了4.89倍, Propionibacteriales、Streptosporangiales、Streptomycetales和Frankiales分别提高了2.81、2.77、2.48和2.22倍。相比之下, 利用细菌通用引物检出Solirubrobacterales和Gaiellales的百分比更高, 分别提高3.4和2.83倍(图 2)。

通过以上比较分析表明, 利用放线菌相关引物可以提高放线菌的百分比含量, 更多目、科和属被检测到, 这与前人的研究一致(Mcveigh et al, 1996; Heuer et al, 1997; Lüdemann et al, 2000; Stach et al, 2003; Schäfer et al, 2010)。以前的研究报道, 某些微生物类群, 特别是具有高G+C含量的类群(如放线菌)在16S rRNA基因库中被低估(Hill et al, 2006)。细菌16S rDNA通用引物不能扩增环境样品中所有放线菌的该基因片段, 而专门设计的放线菌相关引物可大大提高环境样品中放线菌16S rDNA的扩增概率(Mcveigh et al, 1996; Heuer et al, 1997; Lüdemann et al, 2000; Stach et al, 2003)。Stach等(2003)报道, 利用放线菌相关引物扩增环境样品时, 约75% PCR产物序列属于放线菌门, 本研究中为41.56%, 这说明放线菌相关引物更适合于环境样品中放线菌多样性的分析。另外, 在非可培养水平上, 利用放线菌相关引物专门针对红树林放线菌多样性的研究未见报道, 目前文献中主要利用细菌通用引物研究红树林细菌多样性, 其中放线菌(Actinobacteria)所占比例较低, 所占百分比在以下研究地点分别为: 香港Mai Po Ramsar湿地为2.1% (Jiang et al, 2013)和3.5% (Wang et al, 2012), 巴西São Paulo State、Rio de Janeiro state Ilha Grande和Bahia state Porto Seguro红树林湿地为5.4%~12.2% (Andreote et al, 2012)、8.4%和7.5% (Thompson et al, 2013), 马来西亚Rantau Abang红树林湿地为4.55% (Chan et al, 2015)、深圳湾红树林湿地2.2% (Zhang et al, 2015), 本研究中利用细菌通用引物检测到的放线菌百分比是16.79%, 而用放线菌相关引物检测到的百分比为41.56%, 可见放线菌相关引物可提高自然环境中放线菌类群的检测水平。此外, 对于Corynebacteriales类群, 放线菌相关引物检出的百分率(17.25%)高于细菌通用引物(0.94%), 这可能是细菌通用引物对该类群也存在一定的低估所致。

本研究中利用放线菌相关引物和细菌通用引物检测微生物多样性时, 4个目(Acidimicrobiales、Gaiellales、Kineosporiales和Solirubrobacterales)和3个属(Gaiella、Acidothermus和Ilumatobacter)相对丰度都较高。Acidothermaceae科中的Acidothermus属中只有一个种Acidothermus cellulolyticus, 代表菌株具有嗜热、嗜酸性和分解纤维能力(Mohagheghi et al, 1986), 而红树林土壤呈酸性, 且含有大量来自植物落叶的纤维素和木质素, 这说明这类细菌对环境的适应性, 及其可能参与了红树林有机碳的代谢。Mycobacterium是利用放线菌相关引物检测时发现的丰度最高的属, 这类微生物广泛存在于酸性环境中, 与红树林土壤酸性环境相适应; 该属物种最主要特征是细胞壁比其他细菌厚, 疏水、蜡质且富含霉菌酸(Faller et al, 2004), 细胞壁由疏水霉酸酯层和由阿拉伯半乳聚糖连接在一起的肽聚糖层组成, 对植物的耐寒性有重要贡献, 细胞壁这些组成成分的生物合成途径也成为结核病新药的潜在靶点, 可见, 红树林放线菌是蕴藏着丰富的可用于海洋药物开发的放线菌资源。

2.2 在培养水平上放线菌多样性通过传统培养法, 本研究共分离得到放线菌256株, 其中通过水浴55 ℃加热土壤样品分离到207株, 120 ℃加热1 h土壤样品分离到49株。利用不同培养基分离到的菌株数量也不同, 利用高氏合成一号培养基分离得到的菌株数量最多(共105株), 其次是利用腐殖酸维生素培养基分离到80株, 利用土壤提取物培养基分离到71株。将纯化菌株与数据库中的模式菌株做16S rDNA相似性分析, 相似性100%的有58株细菌, 相似性99.0%~99.9%有155株, 相似性98.5%~ 98.9%有25株, 相似性98.0%~98.5%有11株, 相似性低于98%的有2株, 分别是菌株HA161004和HA161010, 这两株菌与Amycolatopsis thermoflava N1165T相似性为95.56%和96.80% (表 1), 表明是潜在新种(Tindall et al, 2010)。在分离放线菌时, 对于相似性低于98.5%的13株潜在新种放细菌, 从不同样品处理方法来看, 其中4株是通过将土壤样品水浴55 ℃加热分离到, 9株是通过将土壤样品120 ℃加热1 h分离到; 从不同培养基来看, 其中6株利用腐殖酸维生素培养基分离到, 7株利用土壤提取物培养基分离到, 由此可知, 为获得更多的新种资源, 需要尝试不同的样品处理方法和多种培养基。

| 菌株名称 | 序列接收号 | 最相似模式菌及相似性 | 抗病原菌活性 | 菌株名称 | 序列接收号 | 最相似模式菌及相似性 | 抗病原菌活性 | |

| HA13696 | MF573412 | Actinomadura formosensis JCM 7474(T) 98.83% | C | HA13690 | KJ467040 | Micromonospora narathiwatensis BTG4-1(T) 99.25% | C | |

| HA161003 | MF573492 | Allostreptomyces psammosilenae YIM DR4008(T) 98.75% | - | HA161155 | MF573431 | Micromonospora sediminicola SH2-13(T) 99.78% | C/V | |

| HA161006 | MF573495 | Amycolatopsis dongchuanensis YIM 75904(T) 99.87% | C | HA13626 | MF573358 | Micromonospora siamensis TT2-4(T) 98.88% | C/V | |

| HA161004 | MF573493 | Amycolatopsis thermoflava N1165(T) 95.56% | - | HA13677 | MF573397 | Micromonospora siamensis TT2-4(T) 99.03% | - | |

| HA161010 | MF573499 | Amycolatopsis thermoflava N1165(T) 96.80% | - | HA13691 | MF573408 | Micromonospora siamensis TT2-4(T) 99.63% | - | |

| HA161018 | MF573504 | Amycolatopsis thermoflava N1165(T) 99.43% | - | HA13597 | MF573336 | Micromonospora chalcea DSM 43026(T) 99.86% | V | |

| HA161043 | MF573511 | Amycolatopsis tucumanensis ABO(T)99.87% | C | HA13609 | MF573345 | Micromonospora chalcea DSM 43026(T) 99.47% | V | |

| HA13601 | MF573339 | Blastococcus jejuensis KST3-10(T) 98.87% | F | HA13604 | MF573341 | Micromonospora tulbaghiae TVU1(T) 100.00% | C | |

| HA13583 | MF573329 | Jishengella endophytica 202201(T) 99.74% | - | HA13628 | MF573360 | Micromonospora tulbaghiae TVU1(T) 99.26% | C | |

| HA13611 | MF573346 | Jishengella endophytica 202201(T) 99.78% | - | HA13645 | KJ467029 | Micromonospora tulbaghiae TVU1(T) 99.55% | C | |

| HA13651 | KJ467031 | Jishengella endophytica 202201(T) 99.16% | - | HA161200 | MF573441 | Micromonospora tulbaghiae DSM 45142(T) 99.27% | - | |

| HA161222 | MF573445 | Krasilnikoviella muralis T6220-5-2b(T) 99.72% | C | HA13701 | MF573417 | Micromonospora maritima D10-9-5(T) 99.78% | C | |

| HA13687 | MF573405 | Microbispora bryophytorum NEAU-TX2-2(T) 99.55% | V | HA13695 | MF573411 | Micromonospora gifhornensis DSM 44337(T) 99.60% | C | |

| HA13712 | MF573425 | Microbispora rosea subsp. Rosea ATCC 12950(T) 99.25% | C | HA13698 | MF573414 | Micromonospora gifhornensis DSM 44337(T) 99.78% | C | |

| HA13587 | MF573330 | Micromonospora aurantiaca ATCC 27029(T) 100.00% | - | HA13615 | KJ467025 | Micromonospora sediminis MS426(T) 99.40% | - | |

| HA13600 | MF573338 | Micromonospora aurantiaca ATCC 27029(T) 99.92% | - | HA161257 | MF573473 | Nocardia grenadensis NBRC 108939(T) 100.00% | C/F | |

| HA13638 | MF573368 | Micromonospora aurantiaca ATCC 27029(T) 99.85% | - | HA13589 | MF573332 | Nonomuraea ferruginea IFO 14094(T) 99.17% | - | |

| HA13655 | KJ467032 | Micromonospora aurantinigra TT1-11(T) 100.00% | C/F | HA13710 | MF573424 | Nonomuraea ferruginea IFO 14094(T) 99.44% | - | |

| HA13664 | MF573388 | Micromonospora carbonacea DSM 43815(T) 99.63% | C/F | HA13713 | MF573426 | Nonomuraea ferruginea IFO 14094(T) 99.26% | - | |

| HA13702 | KJ467042 | Micromonospora carbonacea DSM 43815(T) 98.65% | F | HA13684 | MF573403 | Nonomuraea maritima FXJ7 203(T) 99.63% | - | |

| HA13675 | MF573395 | Micromonospora carbonacea DSM 43815(T) 99.13% | C/F | HA13665 | MF573389 | Nonomuraea turkmeniaca IFO 13155(T) 99.18% | - | |

| HA161188 | MF573437 | Micromonospora chaiyaphumensis DSM 45246(T) 99.22% | - | HA161260 | MF573476 | Rhodococcus rhodochrous NBRC 16069(T) 98.07% | C | |

| HA13612 | KJ467024 | Micromonospora chalcea DSM 43026(T) 99.32% | C | HA161015 | MF573502 | Streptomyces albogriseolus NRRL B-1305(T) 99.86% | C | |

| HA13614 | MF573348 | Micromonospora chalcea DSM 43026(T) 99.47% | C/V | HA161132 | MF573544 | Streptomyces albogriseolus NRRL B-1305(T) 99.87% | C | |

| HA13616 | MF573349 | Micromonospora chalcea DSM 43026(T) 99.78% | C/F | HA161236 | MF573455 | Streptomyces albogriseolus NRRL B-1305(T) 100.00% | C | |

| HA13620 | MF573352 | Micromonospora chalcea DSM 43026(T) 99.85% | C/F/V | HA161081 | MF573520 | Streptomyces antibioticus NBRC 12838(T) 100.00% | F | |

| HA13640 | MF573369 | Micromonospora chalcea DSM 43026(T) 99.77% | C/F | HA161167 | MF573551 | Streptomyces atrovirens NRRL B-16357(T) 99.04% | F | |

| HA13667 | MF573390 | Micromonospora chalcea DSM 43026(T) 99.85% | C | HA161229 | MF573451 | Streptomyces badius NRRL B-2567(T) 100.00% | V | |

| HA13679 | MF573399 | Micromonospora chalcea DSM 43026(T) 99.55% | C/F | HA13685 | MF573404 | Streptomyces cellostaticus NBRC 12849(T) 99.12% | C | |

| HA161291 | MF573489 | Micromonospora chalcea DSM 43026(T) 99.61% | C/E | HA161231 | MF573453 | Streptomyces chumphonensis K1-2(T) 99.87% | M/V | |

| HA13650 | KJ467030 | Micromonospora chalyaphumensis MC5-1(T) 99.33% | - | HA161264 | MF573477 | Streptomyces chumphonensis K1-2(T) 99.74% | M/V | |

| HA13606 | MF573342 | Micromonospora chokoriensis 2-19/6(T) 99.70% | C | HA161239 | MF573458 | Streptomyces coelicoflavus NBRC 15399(T) 100.00% | C/M | |

| HA13632 | MF573364 | Micromonospora chokoriensis 2-19/6(T) 98.88% | V | HA161048 | MF573514 | Streptomyces coeruleorubidus ISP 5145(T) 98.55% | C | |

| HA13658 | MF573382 | Micromonospora chokoriensis 2-19/6(T) 99.48% | C | HA13683 | MF573402 | Streptomyces diastaticus subsp.ardesiacus NRRL B-1773(T) 99.63% | C | |

| HA13681 | KJ467038 | Micromonospora chokoriensis 2-19/6(T) 98.81% | V | HA161096 | MF573532 | Streptomyces griseoflavus LMG 19344(T) 99.23% | - | |

| HA13613 | MF573347 | Micromonospora coxensis 2-30-B/28(T) 99.55% | C/E | HA161116 | MF573428 | Streptomyces griseoflavus LMG 19344(T) 99.38% | - | |

| HA13693 | KJ467041 | Micromonospora coxensis 2-30-B/28(T) 99.48% | C/E | HA161125 | MF573542 | Streptomyces griseoincarnatus LMG 19316(T) 100.00% | F | |

| HA13635 | MF573366 | Micromonospora eburnea LK2-10(T) 99.33% | C/F | HA161256 | MF573472 | Streptomyces hiroshimensis NBRC 3839(T) 98.58% | F | |

| HA13642 | MF573371 | Micromonospora eburnea LK2-10(T) 98.94% | C | HA161045 | MF573513 | Streptomyces matensis NBRC 12889(T) 98.31% | V | |

| HA13656 | MF573381 | Micromonospora eburnea LK2-10(T) 99.02% | C/F | HA161164 | MF573435 | Streptomyces panacagriGsoil 519(T) 98.12% | M | |

| HA13670 | KJ467036 | Micromonospora eburnea LK2-10(T) 98.72% | C | HA161021 | MF573506 | Streptomyces paucisporeus CGMCC 4.2025(T) 98.70% | F | |

| HA13708 | MF573423 | Micromonospora eburnea LK2-10(T) 98.88% | C | HA13688 | MF573406 | Streptomyces psammoticus NBRC 13971(T) 98.90% | C/F | |

| HA13618 | MF573351 | Micromonospora echinospora ATCC 15837(T) 99.63% | C | HA161080 | MF573519 | Streptomyces puniceus NRRL ISP-5058(T) 99.35% | C/F | |

| HA13666 | KJ467034 | Micromonospora echinospora ATCC 15837(T) 99.09% | V | HA161220 | MF573443 | Streptomyces qinglanensis 172205(T) 99.88% | C | |

| HA13672 | MF573392 | Micromonospora echinospora ATCC 15837(T) 99.46% | C/V | HA161221 | MF573444 | Streptomyces qinglanensis 172205(T) 100.00% | C | |

| HA13686 | KJ467039 | Micromonospora echinospora ATCC 15837(T) 98.80% | C | HA161270 | MF573559 | Streptomyces qinglanensis 172205(T) 99.87% | C | |

| HA161162 | MF573433 | Micromonospora echinospora ATCC 15837(T) 99.55% | V | HA161119 | MF573539 | Streptomyces rameus LMG 20326(T) 100.00% | - | |

| HA161191 | MF573439 | Micromonospora echinospora ATCC 15837(T) 99.57% | E/C | HA161138 | MF573550 | Streptomyces rubiginosohelvolus NBRC 12912(T) 99.76% | - | |

| HA13637 | KJ467027 | Micromonospora halophytica DSM 43026(T) 98.71% | F | HA161225 | MF573447 | Streptomyces sanyensis 219820(T) 99.87% | C/F/M | |

| HA13588 | MF573331 | Micromonospora humi P0402(T) 99.09% | - | HA161227 | MF573449 | Streptomyces sanyensis 219820(T) 100.00% | C/F | |

| HA13592 | MF573334 | Micromonospora humi P0402(T) 99.40% | - | HA161166 | MF573436 | Streptomyces spinoverrucosus NBRC 14228(T) 98.46% | C | |

| HA13668 | MF573391 | Micromonospora humi P0402(T) 99.04% | - | HA161133 | MF573545 | Streptomyces spongiicola HNM0071(T) 99.85% | - | |

| HA13624 | MF573356 | Micromonospora krabiensis MA-2(T) 99.25% | C | HA161240 | MF573459 | Streptomyces sundarbansensis MS1/7(T) 99.73% | C/M | |

| HA13648 | MF573376 | Micromonospora krabiensis MA-2(T) 100.00% | C | HA161094 | MF573530 | Streptomyces sundarbansensis MS1/7(T) 99.61% | C/M | |

| HA13659 | MF573383 | Micromonospora krabiensis MA-2(T) 99.28% | C | HA161249 | MF573467 | Streptomyces thermocarboxydus DSM 44293(T) 99.87% | C | |

| HA161199 | MF573440 | Micromonospora krabiensis MA-2(T) 99.24% | C | HA161001 | MF573491 | Streptomyces thermoviolaceus subsp. Thermoviolaceus DSM 40443(T) 98.40% | M/V | |

| HA13594 | MF573335 | Micromonospora marina JSM1-1(T) 99.55% | C | HA161279 | MF573480 | Streptomyces wuyuanensis CGMCC 4.7042(T) 99.87% | C/F/M | |

| HA13619 | KJ467026 | Micromonospora marina JSM1-1(T) 99.40% | C/V | HA161019 | MF573505 | Streptomyces yanglinensis 1307(T) 98.56% | C/F | |

| HA13625 | MF573357 | Micromonospora marina JSM1-1(T) 99.63% | C/V | HA161029 | MF573509 | Streptomyces yanglinensis 1307(T) 98.70% | C/F | |

| HA13631 | MF573363 | Micromonospora matsumotoense IMSNU 22003(T) 99.51% | C | HA13602 | MF573340 | Streptosporangium amethystogenes subsp.amethystogenes DSM 43179(T) 99.25% | - | |

| HA13639 | KJ467028 | Micromonospora matsumotoense IMSNU 22003(T) 98.54% | C/E | HA161205 | MF573442 | Tsukamurella sinensis HKU51(T) 99.76% | - | |

| HA13643 | MF573372 | Micromonospora matsumotoense IMSNU 22003(T) 98.62% | C/E | |||||

| 注: C: Colletotrichum gloeosporioides; E: Escherichia coli; F: Fusarium oxysporum; M: Staphylococcus aureus; V: Vibrio neocaledonicus; -: 无拮抗活性 | ||||||||

国内外对于红树林土壤放线菌资源的分离收集已有大量研究(Usha et al, 2010; Rosmine et al, 2016; Ser et al, 2016a, 2016b; Ariffin et al, 2017; Arumugam et al, 2017; Law et al, 2017; Huang et al, 2018; Asha et al, 2021), 从红树林中分离鉴定的放线菌共有8亚目11科24属(Xu et al, 2014)。本研究分离得到的放线菌属于7个目, Micromonosporales (46.48%)、Streptomycetales (42.92%)、Actinomycetales (4.69%)、Streptosporangiales (3.13%)、Corynebacteriales (1.95%)、Frankiales (0.39%)和Micrococcales (0.39%); 9个科; 14个属, Actinomadura、Allostreptomyces、Amycolatopsis、Blastococcus、Micromonospora、Jishengella、Krasilnikoviella、Microbispora、Nocardia、Nonomuraea、Rhodococcus、Streptomyces、Streptosporangium和Tsukamurella, 其中Streptomyces (42.58%)和Micromonospora (42.19%)是优势属(表 1)。本研究获得的可培养放线菌多样性指数为1.32, 用同样方法对其他地点的红树林土壤可培养放线菌多样性进行了评估, 其中在海南三亚沿海红树林土壤(冯玲玲等, 2018)、海南西海岸真红树根系土壤(候师师等, 2020)、广西茅尾海红树林植物根际土壤(叶景静等, 2018)、印度洋红树林沉积物(何洁等, 2012)、马来西亚红树林土壤(Lee et al, 2014)和印度南部沿海红树林土壤(Arumugam et al, 2017)中可培养放线菌多样性指数分别为1.74、1.75、1.61、2.16、1.44、0.63, 通过比较可知从印度洋红树林沉积物分离得到的放线菌多样性较高, 可能与选用的培养基种类多有关, 在该研究中选用了24种唯一碳源分离培养基, 可见选用多种不同的培养基对于获得多样的菌株是很重要的, 本研究后续将继续选用其他培养基分离放线菌, 以期获得更多样的种类。通过与非培养水平放线菌多样性对比分析, 利用扩增子高通量测序能检测到更高的多样性(通过放线菌相关引物和细菌通用引物得到的放线菌多样性指数分别为2.96和2.41), 表明与传统培养法相比, 分子方法在发现微生物多样性方面更有效(Li et al, 2014)。并非所有培养的细菌都在土壤环境DNA样本中被检测到, 例如属于Actinomadura、Micromonospora、Nocardia和Streptomyces的可培养菌株在DNA样本中存在, 但其他10个属, 包括Allostreptomyces、Amycolatopsis、Blastococcus、Jishengella、Krasilnikoviella、Microbispora、Nonomuraea、Rhodococcus、Streptosporangium和Tsukamurella, 没有被检测到。在环境DNA中未检测到, 可能与这10个属的丰度低有关系, 导致提取DNA的难度较大。

以往研究表明Streptomyces、Micromonospora和Rhodococcus是海洋沉积物中常被分离到的放线菌(Maldonado et al, 2005; Bredholdt et al, 2007; Duncan et al, 2015; Huang et al, 2018)。郑志成等(1989)从红树林根际土壤中分离到的放线菌中Streptomyces占75. 7%。Eccleston等(2008)从澳大利亚Sunshine Coast红树林土壤中分离到放线菌主要为Micromonospora。在本研究中分离到最多的是Streptomyces, 其中有菌株(HA161045、HA161164、HA161166、HA161001)与模式菌株的相似性较低(表 1), 是潜在新种。本研究还分到大量的稀有放线菌, 如Micromonospora、Actinomadura、Allostreptomyces、Nocardia、Nonomuraea等。稀有放线菌的分离通常需要预处理或者复杂的富集培养过程(Janssen et al, 2002; Jensen et al, 2005; Pathom-Aree et al, 2006; Bredholdt et al, 2007; Solano et al, 2009)。例如本研究中大量的Micromonospora菌株就是通过将土壤样品进行55 ℃水浴后在腐殖酸维生素培养基分离到, 其中包括一些潜在新种(如菌株HA13702、HA13639、HA13643)(表 1)。近年来已经发表许多新种, 例如Streptomyces xiamenensis (Xu et al, 2009)、Streptomyces colonosanans (Law et al, 2017)、Streptomyces malaysiense (Ser et al, 2016a)、Micromonospora rifamycinica (Huang et al, 2008)、Pseudonocardia nematodicida (Liu et al, 2015)、Nocardiopsis mangrovei (Huang et al, 2015)。此外, 本研究在非培养水平放线菌多样性分析中得到大量的未分类或者未培养放线菌, 所有以上研究结果表明红树林湿地中分布着大量未被挖掘的放线菌资源, 是发现新的放线菌的关键区域。

2.3 拮抗病原菌活性测定放线菌因其可产生许多重要的具有生物活性的天然产物, 因此, 仍是生物技术领域最有用的微生物之一(Sharon et al, 2014; Xu et al, 2014)。本研究对123株代表性菌株进行了病原微生物拮抗活性测定, 其中来自9个属(Actinomadura、Amycolatopsis、Blastococcus、Krasilnikoviella、Microbispora、Micromonospora、Nocardia、Rhodococcus、Streptomyces)的92株被测菌株(占总菌株数的74.8%)具有病原微生物拮抗活性, 其中对1种病原微生物有拮抗活性的菌株数量是57, 2种的菌株数量是32, 3种的菌株数量是3(分别是菌株HA161225/ HA161279/ HA1362)(表 1)。来自Streptomyces和Micromonospora两个属的大部分菌株对至少1种病原菌是有拮抗活性的, 活性菌株数量分别是32和50。所有被测菌株中有71株(占总菌株数的57.7%)对Colletotrichum gloeosporioides有拮抗活性, 25株(占总菌株数的20.3%)对Fusarium oxysporum有拮抗活性, 6株(占总菌株数的4.9%)对Escherichia coli有拮抗活性, 9株(占总菌株数的7.3%)对Staphylococcus aureus有拮抗活性, 19株(占总菌株数的15.4%)对Vibrio neocaledonicus有拮抗活性。

来自Streptomyces的成员可产生天然抗生素(Kinkel et al, 2014; Ser et al, 2016a)和多种具有抗菌、抗癌、抗氧化和免疫抑制活性的化合物(Rashad et al, 2015; Ser et al, 2016b; Law et al, 2017; 候师师等, 2020)。已有研究报道, 红树林放线菌中Streptomyces是天然产物的最主要来源, 其次是Micromonospora (Xu et al, 2014), 本研究也得到相似的结果, 作为天然产物主要来源的红树林放线菌已成为天然药物研究的热点。此外, 来自Amycolatopsis和Nocardia两个属的菌株具有拮抗Colletotrichum gloeosporioides和Fusarium oxysporum的活性, 类似结果在以前的研究中也有报道(Singh et al, 2007; Zhang et al, 2008; 奚逢源等, 2014)。来自以下属Actinomadura、Blastococcus、Krasilnikoviella和Microbispora的抗菌活性以往未见报道, 在本研究中检测到了病原菌拮抗活性, 可用于后续菌株的开发利用。本研究中来自Allostreptomyces、Jishengella、Nonomuraea、Streptosporangium和Tsukamurella的菌株没有检测到抗病原菌活性。由于抗菌活性物质的产生受到培养基、pH值和培养温度等因素的影响, 因此, 下一步将研究不同培养条件下菌株的抗菌活性检测, 以便为菌株开发利用提供前期基础数据支撑。

3 结论本研究在培养水平和非培养水平分别对八门湾红树林湿地土壤中放线菌的多样性及其抗病原菌活性进行了分析。对于非培养水平多样性, 与细菌通用引物相比, 利用放线菌相关引物可以提高放线菌丰度的检测水平, 可以检测到放线菌门更多的目、科和属; 优势类群在两对不同引物得到的结果中的百分含量差异较大; 放线菌相关引物更适合环境样品中放线菌多样性的分析。本研究获得的可培养放线菌多样性指数为1.32, Streptomyces (42.58%)和Micromonospora (42.19%)是优势属; 与模式菌株的相似性小于98.5%有13株, 是潜在新种。与传统培养法相比, 基于分子生物学的方法可以检测到更高的微生物多样性。来自9个属的92株(74.8%)代表性菌株具有抗病原菌活性, 其中对Colletotrichum gloeosporioides、Fusarium oxysporum、Escherichia coli、Staphylococcus aureus和Vibrio neocaledonicus有拮抗活性的菌株数量分别为71、25、6、9和19株。

电子附件材料:

冯玲玲, 杨芹, 张露, 等, 2018. 海南三亚红树林放线菌多样性及抗菌活性. 中国抗生素杂志, 43(11): 1355-1363 DOI:10.3969/j.issn.1001-8689.2018.11.006 |

叶景静, 郑红芸, 吴越, 等, 2018. 广西茅尾海红树林植物根际土壤放线菌多样性及抗菌活性研究. 中国病原生物学杂志, 13(11): 1221-1226, 1231 |

何洁, 张道锋, 徐盈, 等, 2012. 印度洋红树林沉积物可培养海洋放线菌多样性及其活性. 微生物学报, 52(10): 1195-1202 |

郑志成, 周美英, 姚炳新, 1989. 红树林根际放线菌的组成及生物活性. 厦门大学学报(自然科学版), 28(3): 306-310 DOI:10.3321/j.issn:0438-0479.1989.03.019 |

洪葵, 2013. 红树林放线菌及其天然产物研究进展. 微生物学报, 53(11): 1131-1141 |

候师师, 李蜜, 姜舒, 等, 2020. 海南西海岸四种真红树根系土壤放线菌物种多样性及其延缓衰老活性初筛. 广西植物, 40(3): 320-326 |

奚逢源, 薛长艳, 郝之奎, 2014. Nocardia asteroides XI的鉴定及抗菌活性研究. 中国抗生素杂志, 39(5): 394-398 DOI:10.3969/j.issn.1001-8689.2014.05.015 |

ALONGI D M, 1996. The dynamics of benthic nutrient pools and fluxes in tropical mangrove forests. Journal of Marine Research, 54(1): 123-148 DOI:10.1357/0022240963213475 |

ALONGI D M, 2008. Mangrove forests: resilience, protection from tsunamis, and responses to global climate change. Estuarine, Coastal and Shelf Science, 76(1): 1-13 DOI:10.1016/j.ecss.2007.08.024 |

AMRITA K, NITIN J, DEVI C S, 2012. Novel bioactive compounds from mangrove derived Actinomycetes. International Research Journal of Pharmacy, 3(9): 25-29 |

ANDREOTE F D, JIMÉNEZ D J, CHAVES D, et al, 2012. The microbiome of Brazilian mangrove sediments as revealed by metagenomics. PLoS One, 7(6): e38600 DOI:10.1371/journal.pone.0038600 |

ARIFFIN S, ABDULLAH M F F, MOHAMAD S A S, 2017. Identification and antimicrobial properties of Malaysian mangrove actinomycetes. International Journal on Advanced Science, Engineering and Information Technology, 7(1): 71-77 DOI:10.18517/ijaseit.7.1.1113 |

ARUMUGAM T, KUMAR P S, KAMESHWAR R, et al, 2017. Screening of novel actinobacteria and characterization of the potential isolates from mangrove sediment of south coastal India. Microbial Pathogenesis, 107: 225-233 DOI:10.1016/j.micpath.2017.03.035 |

ASHA K, BHADURY P, 2021. Myceligenerans indicum sp. nov., an actinobacterium isolated from mangrove sediment of Sundarbans, India. Archives of Microbiology, 203(4): 1577-1585 DOI:10.1007/s00203-020-02150-0 |

BREDHOLDT H, GALATENKO O A, ENGELHARDT K, et al, 2007. Rare actinomycete bacteria from the shallow water sediments of the Trondheim fjord, Norway: isolation, diversity and biological activity. Environmental Microbiology, 9(11): 2756-2764 DOI:10.1111/j.1462-2920.2007.01387.x |

CAPORASO J G, KUCZYNSKI J, STOMBAUGH J, et al, 2010. QⅡME allows analysis of high-throughput community sequencing data. Nature Methods, 7(5): 335-336 DOI:10.1038/nmeth.f.303 |

CHAN K G, ISMAIL Z, 2015. Tropical soil metagenome library reveals complex microbial assemblage. BioRxiv DOI:10.1101/018895 |

CLAVERÍAS F P, UNDABARRENA A, GONZÁLEZ M, et al, 2015. Culturable diversity and antimicrobial activity of Actinobacteria from marine sediments in Valparaíso bay, Chile. Frontiers in Microbiology, 6: 737 |

DEMAIN A L, SANCHEZ S, 2009. Microbial drug discovery: 80 years of progress. The Journal of Antibiotics, 62(1): 5-16 DOI:10.1038/ja.2008.16 |

DIAS A C F, DINI-ANDREOTE F, TAKETANI R G, et al, 2011. Archaeal communities in the sediments of three contrasting mangroves. Journal of Soils and Sediments, 11(8): 1466-1476 DOI:10.1007/s11368-011-0423-7 |

DUNCAN K R, HALTLI B, GILL K A, et al, 2015. Exploring the diversity and metabolic potential of actinomycetes from temperate marine sediments from Newfoundland, Canada. Journal of Industrial Microbiology and Biotechnology, 42(1): 57-72 DOI:10.1007/s10295-014-1529-x |

ECCLESTON G P, BROOKS P R, KURTBÖKE D I, 2008. The occurrence of bioactive micromonosporae in aquatic habitats of the sunshine coast in Australia. Marine Drugs, 6(2): 243-261 DOI:10.3390/md6020243 |

FALLER M, NIEDERWEIS M, SCHULZ G E, 2004. The structure of a mycobacterial outer-membrane channel. Science, 303(5661): 1189-1192 DOI:10.1126/science.1094114 |

FARRIS M H, OLSON J B, 2007. Detection of Actinobacteria cultivated from environmental samples reveals bias in universal primers. Letters in Applied Microbiology, 45(4): 376-381 DOI:10.1111/j.1472-765X.2007.02198.x |

SHARON S, KALIDASS S, 2014. Antimicrobial activity of marine actinomycetes Streptomyces Dhinakaran 2011 (JF751041). International Multidisciplinary Research Journal, 5(1): 158-164 |

HAYAKAWA M, OTOGURO M, TAKEUCHI T, et al, 2000. Application of a method incorporating differential centrifugation for selective isolation of motile actinomycetes in soil and plant litter. Antonie Van Leeuwenhoek, 78(2): 171-185 DOI:10.1023/A:1026579426265 |

HEUER H, KRSEK M, BAKER P, et al, 1997. Analysis of actinomycete communities by specific amplification of genes encoding 16S rRNA and gel-electrophoretic separation in denaturing gradients. Applied and Environmental Microbiology, 63(8): 3233-3241 DOI:10.1128/aem.63.8.3233-3241.1997 |

HILL J E, TOWN J R, HEMMINGSEN S M, 2006. Improved template representation in cpn60 polymerase chain reaction (PCR) product libraries generated from complex templates by application of a specific mixture of PCR primers. Environmental Microbiology, 8(4): 741-746 DOI:10.1111/j.1462-2920.2005.00944.x |

HUANG H Q, LIU M, ZHONG W D, et al, 2018. Streptomyces caeni sp. nov., isolated from mangrove mud. International Journal of Systematic and Evolutionary Microbiology, 68(10): 3080-3083 DOI:10.1099/ijsem.0.002916 |

HUANG H Q, LV J S, HU Y H, et al, 2008. Micromonospora rifamycinica sp. nov., a novel actinomycete from mangrove sediment. International Journal of Systematic and Evolutionary Microbiology, 58(1): 17-20 DOI:10.1099/ijs.0.64484-0 |

HUANG H Q, XING S S, YUAN W D, et al, 2015. Nocardiopsis mangrovei sp. nov., isolated from mangrove sediment. Antonie Van Leeuwenhoek, 107(6): 1541-1546 DOI:10.1007/s10482-015-0447-x |

JANSSEN P H, YATES P S, GRINTON B E, et al, 2002. Improved culturability of soil bacteria and isolation in pure culture of novel members of the divisions Acidobacteria, Actinobacteria, Proteobacteria, and Verrucomicrobia. Applied and Environmental Microbiology, 68(5): 2391-2396 DOI:10.1128/AEM.68.5.2391-2396.2002 |

JENSEN P R, GONTANG E, MAFNAS C, et al, 2005. Culturable marine actinomycete diversity from tropical Pacific Ocean sediments. Environmental Microbiology, 7(7): 1039-1048 DOI:10.1111/j.1462-2920.2005.00785.x |

JIANG X T, PENG X, DENG G H, et al, 2013. Illumina sequencing of 16S rRNA tag revealed spatial variations of bacterial communities in a mangrove wetland. Microbial Ecology, 66(1): 96-104 DOI:10.1007/s00248-013-0238-8 |

KAMEI Y, ISNANSETYO A, 2003. Lysis of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus by 2, 4-diacetylphloroglucinol produced by Pseudomonas sp. AMSN isolated from a marine alga. International Journal of Antimicrobial Agents, 21(1): 71-74 DOI:10.1016/S0924-8579(02)00251-0 |

KINKEL L L, SCHLATTER D C, XIAO K, et al, 2014. Sympatric inhibition and niche differentiation suggest alternative coevolutionary trajectories among Streptomycetes. The ISME Journal, 8(2): 249-256 DOI:10.1038/ismej.2013.175 |

LAW W F, SER H L, DUANGJAI A, et al, 2017. Streptomyces colonosanans sp. nov., a novel actinobacterium isolated from Malaysia mangrove soil exhibiting antioxidative activity and cytotoxic potential against human colon cancer cell lines. Frontiers in Microbiology, 8: 877 DOI:10.3389/fmicb.2017.00877 |

LEE L H, ZAINAL N, AZMAN A S, et al, 2014. Diversity and antimicrobial activities of Actinobacteria isolated from tropical mangrove sediments in Malaysia. The Scientific World Journal: 698178 |

LI H, ZHONG Q P, WIRTH S, et al, 2014. Diversity of autochthonous bacterial communities in the intestinal mucosa of grass carp (Ctenopharyngodon idellus) (Valenciennes) determined by culture-dependent and culture-independent techniques. Aquaculture Research, 46(10): 2344-2359 |

LIU M, CUI Y, CHEN Y Q, et al, 2017. Diversity of Bacillus-like bacterial community in the sediments of the Bamenwan mangrove wetland in Hainan, China. Canadian Journal of Microbiology, 63(3): 238-245 DOI:10.1139/cjm-2016-0449 |

LIU M, XING S S, YUAN W D, et al, 2015. Pseudonocardia nematodicida sp. nov., isolated from mangrove sediment in Hainan, China. Antonie Van Leeuwenhoek, 108(3): 571-577 DOI:10.1007/s10482-015-0512-5 |

LÜDEMANN H, CONRAD R, 2000. Molecular retrieval of large 16S rRNA gene fragments from an Italian rice paddy soil affiliated with the class Actinobacteria. Systematic and Applied Microbiology, 23(4): 582-584 DOI:10.1016/S0723-2020(00)80033-8 |

MALDONADO L A, STACH J E M, PATHOM-AREE W, et al, 2005. Diversity of cultivable actinobacteria in geographically widespread marine sediments. Antonie Van Leeuwenhoek, 87(1): 11-18 DOI:10.1007/s10482-004-6525-0 |

MCVEIGH H P, MUNRO J, EMBLEY T M, 1996. Molecular evidence for the presence of novel actinomycete lineages in a temperate forest soil. Journal of Industrial Microbiology, 17(3/4): 197-204 |

MENDES L W, TAKETANI R G, NAVARRETE A A, et al, 2012. Shifts in phylogenetic diversity of archaeal communities in mangrove sediments at different sites and depths in southeastern Brazil. Research in Microbiology, 163(5): 366-377 DOI:10.1016/j.resmic.2012.05.005 |

MEVS U, STACKEBRANDT E, SCHUMANN P, et al, 2000. Modestobacter multiseptatus gen. nov., sp. nov., a budding actinomycete from soils of the Asgard Range (Transantarctic Mountains). International Journal of Systematic and Evolutionary Microbiology, 50: 337-346 DOI:10.1099/00207713-50-1-337 |

MOHAGHEGHI A, GROHMANN K, HIMMEL M, et al, 1986. Isolation and characterization of Acidothermus cellulolyticus gen. nov., sp. nov., a new genus of thermophilic, acidophilic, cellulolytic bacteria. International Journal of Systematic and Evolutionary Microbiology, 36(3): 435-443 |

PAGE K A, CONNON S A, GIOVANNONI S J, 2004. Representative freshwater bacterioplankton isolated from Crater Lake, Oregon. Applied and Environmental Microbiology, 70(11): 6542-6550 DOI:10.1128/AEM.70.11.6542-6550.2004 |

PATHOM-AREE W, STACH J E M, WARD A C, et al, 2006. Diversity of actinomycetes isolated from challenger deep sediment (10, 898 m) from the mariana trench. Extremophiles, 10(3): 181-189 DOI:10.1007/s00792-005-0482-z |

RASHAD F M, FATHY H M, EL-ZAYAT A S, et al, 2015. Isolation and characterization of multifunctional Streptomyces species with antimicrobial, nematicidal and phytohormone activities from marine environments in Egypt. Microbiological Research, 175: 34-47 DOI:10.1016/j.micres.2015.03.002 |

ROSMINE E, VARGHESE S A, 2016. Isolation of actinomycetes from mangrove and estuarine sediments of Cochin and screening for antimicrobial activity. Journal of Coastal Life Medicine, 4(3): 207-210 DOI:10.12980/jclm.4.2016j5-148 |

SCHÄFER J, JÄCKEL U, KÄMPFER P, 2010. Development of a new PCR primer system for selective amplification of Actinobacteria. FEMS Microbiology Letters, 311(2): 103-112 DOI:10.1111/j.1574-6968.2010.02069.x |

SER H L, PALANISAMY U D, YIN W F, et al, 2016a. Streptomyces malaysiense sp. nov.: A novel Malaysian mangrove soil actinobacterium with antioxidative activity and cytotoxic potential against human cancer cell lines. Scientific Reports, 6: 24247 DOI:10.1038/srep24247 |

SER H L, TAN L T H, PALANISAMY U D, et al, 2016b. Streptomyces antioxidans sp. nov., a novel mangrove soil actinobacterium with antioxidative and neuroprotective potentials. Frontiers in Microbiology, 7: 899 |

SINGH S B, OCCI J, JAYASURIYA H, et al, 2007. Antibacterial evaluations of thiazomycin-a potent thiazolyl peptide antibiotic from amycolatopsis fastidiosa. The Journal of Antibiotics, 60(9): 565-571 DOI:10.1038/ja.2007.71 |

SOLANO G, ROJAS-JIMÉNEZ K, JASPARS M, et al, 2009. Study of the diversity of culturable actinomycetes in the North Pacific and Caribbean coasts of Costa Rica. Antonie Van Leeuwenhoek, 96(1): 71-78 DOI:10.1007/s10482-009-9337-4 |

STACH J E M, MALDONADO L A, WARD A C, et al, 2003. New primers for the class Actinobacteria: application to marine and terrestrial environments. Environmental Microbiology, 5(10): 828-841 DOI:10.1046/j.1462-2920.2003.00483.x |

SUTHINDHIRAN K, KANNABIRAN K, 2010. Diversity and exploration of bioactive marine actinomycetes in the Bay of Bengal of the Puducherry coast of India. Indian Journal of Microbiology, 50(1): 76-82 DOI:10.1007/s12088-010-0048-3 |

THOMPSON C E, BEYS-DA-SILVA W O, SANTI L, et al, 2013. A potential source for cellulolytic enzyme discovery and environmental aspects revealed through metagenomics of Brazilian mangroves. AMB Express, 3(1): 65 DOI:10.1186/2191-0855-3-65 |

TINDALL B J, ROSSELLÓ-MÓRA R, BUSSE H J, et al, 2010. Notes on the characterization of prokaryote strains for taxonomic purposes. International Journal of Systematic and Evolutionary Microbiology, 60(1): 249-266 DOI:10.1099/ijs.0.016949-0 |

USHA R, ANANTHASELVI P, VENIL C K, et al, 2010. Antimicrobial and antiangiogenesis activity of Streptomyces parvulus KUAP106 from mangrove soil. European Journal of Biological Sciences, 2(4): 77-83 |

WANG Y, SHENG H F, HE Y, et al, 2012. Comparison of the levels of bacterial diversity in freshwater, intertidal wetland, and marine sediments by using millions of Illumina tags. Applied and Environmental Microbiology, 78(23): 8264-8271 DOI:10.1128/AEM.01821-12 |

XU J, WANG Y, XIE S J, et al, 2009. Streptomyces xiamenensis sp. nov., isolated from mangrove sediment. International Journal of Systematic and Evolutionary Microbiology, 59(3): 472-476 DOI:10.1099/ijs.0.000497-0 |

XU D B, YE W W, HAN Y, et al, 2014. Natural products from mangrove actinomycetes. Marine Drugs, 12(5): 2590-2613 DOI:10.3390/md12052590 |

YAN B, HONG K, YU Z N, 2006. Archaeal communities in mangrove soil characterized by 16S rRNA gene clones. Journal of Microbiology, 44(5): 566-571 |

ZHANG S P, LIAO S A, YU X Y, et al, 2015. Microbial diversity of mangrove sediment in Shenzhen Bay and gene cloning, characterization of an isolated phytase-producing strain of SPC09 B. cereus. Applied Microbiology and Biotechnology, 99(12): 5339-5350 DOI:10.1007/s00253-015-6405-8 |

ZHANG C W, ZINK D L, USHIO M, et al, 2008. Isolation, structure, and antibacterial activity of thiazomycin A, a potent thiazolyl peptide antibiotic from Amycolatopsis fastidiosa. Bioorganic & Medicinal Chemistry, 16(19): 8818-8823 |

2022, Vol. 53

2022, Vol. 53