中国海洋湖沼学会主办。

文章信息

- 程兆龙, 于国旭, 李永涛, 左涛, 牛明香, 王俊. 2022.

- CHENG Zhao-Long, Yu Guo-Xu, LI Yong-Tao, ZUO Tao, NIU Ming-Xiang, WANG Jun. 2022.

- 黄河口及其邻近水域春季东亚江豚分布规律

- DISTRIBUTION PATTERN OF THE EAST ASIAN FINLESS PORPOISE IN THE HUANGHE RIVER ESTUARY AND ITS ADJACENT WATERS IN SPRING

- 海洋与湖沼, 53(2): 505-512

- Oceanologia et Limnologia Sinica, 53(2): 505-512.

- http://dx.doi.org/10.11693/hyhz20211000259

文章历史

-

收稿日期:2021-10-29

收修改稿日期:2021-12-24

2. 青岛海洋试点国家实验室生态环境功能实验室 山东青岛 266237;

3. 长岛国家海洋公园管理中心 山东烟台 265800

2. Laboratory for Marine Ecology and Environmental Science, Pilot National laboratory for Marine Science and Technology (Qingdao), Qingdao 266237, China;

3. Changdao National Ocean Park Administration Center, Yantai 265800, China

掌握动物的分布规律是针对性制订物种保护措施、开展栖息地管理的关键(Taylor et al, 1993)。特别是沿岸分布的小型齿鲸, 极易受到人类活动影响, 而人类活动强度日益提高, 对其开展分布调查研究显得愈发重要(Read, 2008; Davidson et al, 2012; Notarbartolo di Sciara et al, 2016)。动物的分布规律取决于多方面因素, 对于鲸类这类顶级捕食者而言, 食物往往是决定其分布的决定性因素(Benoit‐Bird et al, 2003; Hastie et al, 2004)。

绝大多数小型齿鲸为机会型捕食者, 他们对食物没有特别选择, 主要以环境中最多或最易捕到的食物为食(Yang et al, 2019)。但有一些例外, 为专一性捕食者, 比如东北太平洋居留型虎鲸(Orcinus orca)几乎只以奇努克鲑鱼(Oncorhynchus tshawytscha)为食(Williams et al, 2011); 比斯开湾的真海豚(Delphinus delphis)偏爱捕食热量密度高的鱼类(Spitz et al, 2010)。

东亚江豚(Neophocaena asiaeorientalis sunameri)隶属于鲸目(Cetacea)、齿鲸亚目(Odontocete)、鼠海豚科(Phocoenidae)、江豚属(Neophocaena), 是窄脊江豚(Neophocaena asiaeorientalis)种下的海水亚种, 是一种典型沿岸分布的小型齿鲸(Jefferson et al, 2011)。国际自然保护联盟(International Union for Conservation of Nature, IUCN)将东亚江豚列为濒危级。2021年2月5日新调整的《国家重点保护野生动物名录》将东亚江豚列为国家二级保护野生动物。

国内对东亚江豚的分布特征研究极其缺乏, 仅有的信息需追溯至20世纪80~90年代或更早(王丕烈, 2012)。东亚江豚主要以硬骨鱼类为食(王丕烈, 2012), 而最近几十年渤海渔业资源衰退严重(Shan et al, 2013, 2014), 东亚江豚的生存现状却是未知的。此外, 最新研究还发现发声鱼类在东亚江豚食谱中占有重要地位(Lobel et al, 2010; Ladich, 2015; Lu et al, 2016; Chen et al, 2017), 其可能具有专一性捕食者的特征。因此, 开展东亚江豚种群生态分布及行为生态学研究具有必要性和紧迫性。

由于江豚体形小、出水快、缺少背鳍(图 1), 生性胆小难以靠近, 以传统的目视方法对野外种群开展生态调查极具挑战(Akamatsu et al, 2008)。而他们在水下发声频繁, 近些年被动声学监测逐渐兴起, 成为江豚生态研究的主流方法(Akamatsu et al, 2008)。

|

| 图 1 渤海东亚江豚 Fig. 1 The East Asian finless porpoises in Bohai Sea |

基于此, 我们在黄河口及其邻近水域开展被动声学调查, 包括(1)通过拖曳式调查监测东亚江豚种群分布特征; (2)通过定点式调查监测发声鱼类分布特征, 以期增进对该水域东亚江豚分布特征及其影响因素的了解, 丰富国内海洋哺乳动物的研究成果, 为将来保护工作的开展提供一定的借鉴。

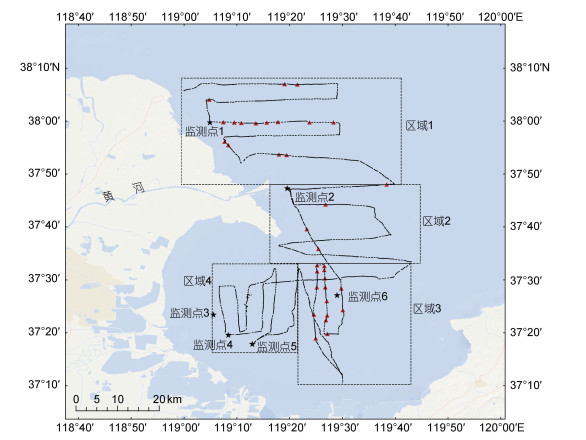

1 材料与方法 1.1 调查区域2019年6月与2021年6月在黄河口及其邻近水域开展被动声学调查, 包括拖曳式调查和定点式调查。调查范围纬度在37°20′~38°10′N之间, 经度在119°00′~119°45′E之间, 调查路线及定点监测位点信息见图 2和表 1。

|

| 图 2 拖曳式被动声学调查路线(黑色实线)、定点式被动声学调查位点(黑色五角星)、东亚江豚发现位点(红色三角形) Fig. 2 The survey line (black lines) and monitoring sites (black stars) of passive acoustic monitoring of East Asian finless porpoises in Huanghe (Yellow) River and its adjacent water 注: 虚线将调查区域划分为4个部分, 区域1为黄河口以北, 区域2为黄河口以南, 区域3为莱州湾中部, 区域4为莱州湾西部 |

| 监测点 | 经纬度 | 监测时间/年-月-日T时: 分 |

| 1 | 37°59.7730′N 119°04.9046′E |

2019-06-14T18:00~2019-06-15T06:20 |

| 2 | 37°47.3106′N 119°19.5386′E |

2019-06-11T19:20~2019-06-12T07:00 |

| 3 | 37°23.4305′N 119°05.5689′E |

2021-06-13T18:00~2021-06-14T17:00 |

| 4 | 37°19.6037′N 119°08.3908′E |

2019-06-18T17:38~2019-06-19T09:20 |

| 5 | 37°17.8801′N 119°12.9447′E |

2019-06-19T18:26~2019-06-20T09:21 |

| 6 | 37°17.8801′N 119°12.9447′E |

2021-06-12T18:10~2021-06-13T13:55 |

拖曳式调查平台是一艘渔船(长约24 m)。调查时船速约为12 km/h, 调查船后拖曳一条拖绳(长100 m), 拖绳尾端绑定一个声学记录仪(SoundTrap 300HF, Ocean Instruments, 新西兰), 声学记录仪前方绑定一个金属棒(重约1 kg), 另外在拖绳上绑定若干泡沫, 以保证声学记录仪既能够下沉到水面下约1 m的深度, 又不会触碰海底(Barlow et al, 2021)。声学记录仪工作时参数设置如下: 连续记录, 高通滤波600 Hz, 高增益(灵敏度约–176.3 dB), 采样率576 kHz。

1.2.2 定点式调查调查平台同拖曳式调查。调查时关闭船只发动机, 绳索一端绑定于船上, 另一端绑定一个铅坠(重约7 kg), 一个声学记录仪(SoundTrap 300HF)绑定于绳索中间, 垂直悬挂在水下约1.5 m的深度(Wang et al, 2014)。声学记录仪工作时设置参数如下: 连续记录, 高增益, 采样率576 kHz。

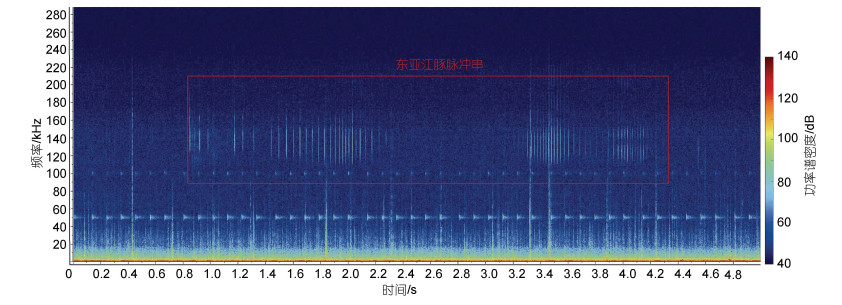

1.3 数据分析 1.3.1 拖曳式调查由于受到考察船噪声的影响, 并且声学记录仪已开启高通滤波功能, 因此拖曳调查产生的声音文件仅用来分析寻找东亚江豚的声信号, 分析过程在Raven Pro软件(版本号1.6)中进行, 采取人工确认的方式判断东亚江豚声信号及其出现的时间(图 3, 5 s汉宁窗, 2 048点快速傅里叶变换, 50%重叠, 0~288 kHz)。

|

| 图 3 东亚江豚发出的脉冲串 Fig. 3 Echolocation click trains of East Asian finless porpoise |

东亚江豚声信号判断标准如下: (1)一个脉冲串至少有5个脉冲信号组成(Li et al, 2010); (2)脉冲的峰值频率在110~150 kHz之间, 且脉冲间隔变化均匀; (3)脉冲波形图与东亚江豚的吻合(Li et al, 2007)。

综合考虑江豚游动速度[(4.57±0.50) km/h, Akamatsu et al, 2002], 调查船航行速度, 声学仪器探测距离(约300 m, Akamatsu et al, 2008), 当上一个东亚江豚脉冲串的结束时间与下一个东亚江豚脉冲串的起始时间超过5 min时, 我们定义其为一个东亚江豚声学目击(acoustic encounter)。

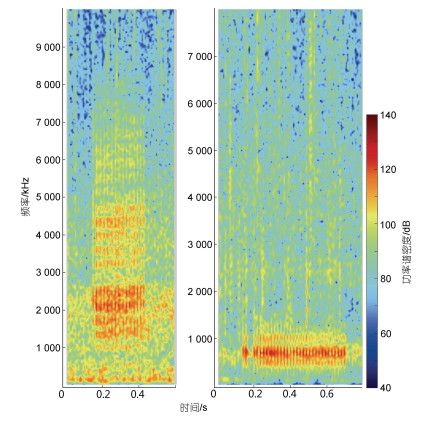

1.3.2 定点式调查分析过程在Raven Pro 1.6软件中进行, 采取人工确认的方式筛选出鱼类的声信号及其出现的时间(5 s汉宁窗, 10 000点快速傅里叶变换, 50%重叠, 0~8 kHz)。鱼类的发声分为三种情况: (1)无, 未记录到鱼类声信号; (2)单个, 鱼类声信号是以单个信号的形式被记录到; (3)合唱, 多个个体同时发声, 大量声信号重叠(Ladich, 2015)。

2 结果 2.1 拖曳式调查累计调查航行710.30 km, 共探测到34个东亚江豚声学目击, 目击分布见图 2。将本研究的调查区域划分为4个部分, 分别为黄河口以北(区域1)、黄河口以南(区域2)、莱州湾中部(区域3)、莱州湾西部(区域4, 图 2), 具体在这4个区域东亚江豚声学目击分别为15, 4, 15, 0个, 调查距离分别为221.89, 155.92, 161.95, 170.54 km, 东亚江豚声学目击密度分别为0.07, 0.03, 0.09, 0.00个/km (图 4)。

|

| 图 4 黄河口及其邻近水域东亚江豚声学目击密度 Fig. 4 Acoustic encounter densities in the four survey regions off the Huanghe River estuary and its adjacent water 注: 粉色区域为黄河口以北, 黄色区域为黄河口以南, 绿色区域为莱州湾中部, 紫色区域为莱州湾西部, 圆柱高度及标注数字表示对应区域东亚江豚声学目击密度 |

累计监测5 842 min, 其中监测点1的监测时长为740 min, 监测点2的监测时长为700 min, 监测点3的监测时长为1 380 min, 监测点4的监测时长为942 min, 监测点5的监测时长为895 min, 监测点6的监测时长为1 185 min。在监测点1发现两种鱼类声信号, 一种频率在1~7 kHz, 将其命名为type1, 发声时间段在19: 20~20: 00之间, 未形成合唱; 另一种频率在1 kHz以下, 将其命名为type2, 发声时间段在01: 55~06: 15之间, 未形成合唱(表 2)。在监测点6发现一种鱼类声信号, 为type2类型, 发声时间段为18: 17~21: 07和06: 07~13: 52, 两个时间段内均形成合唱(表 2)。两种鱼类声信号声谱图见图 5。在其他监测点未发现鱼类声信号。

| 监测点 | 鱼类发声情况 | 发声时段/时: 分 | 发声类型 |

| 1 | 单个 | 19:20~20:00 01:55~06:15 |

type1 type2 |

| 2 | 无 | 无 | 无 |

| 3 | 无 | 无 | 无 |

| 4 | 无 | 无 | 无 |

| 5 | 无 | 无 | 无 |

| 6 | 合唱 | 18:17~21:07 06:07~13:52 |

type2 |

|

| 图 5 两种鱼类声信号的声谱图 Fig. 5 The spectrograms of two types of fish calls |

本研究表明, 春季东亚江豚在黄河口及其邻近水域的分布不均匀, 88.23%的声学目击发生在黄河口以北和莱州湾中部。历史上鲜有对该水域东亚江豚分布特征的研究。仅有的信息来自于《中国鲸类》中的简单描述: “山东沿岸以莱州湾内数量较多, 由黄河口、小清河口近岸至妃姆岛一带均有”(王丕烈, 2012)。本文填补了近些年对其了解的空白。

本研究仅在东亚江豚集中分布的两个水域探测到鱼类发出的声信号, 这说明与其他小型齿鲸一样, 食物是影响东亚江豚分布的重要因素。鱼类发出的声信号通常都具有物种特异性, 本研究记录到的type1鱼类声信号的能量主要集中在1 000~7 000 Hz之间, 峰值频率在2 000~2 500 Hz之间, type2能量主要集中在400~1 000 Hz之间, 峰值频率在400~800 Hz之间, 与许兰英等(1999)描述的渤黄海两种发声鱼类皮氏叫姑鱼(Johnius belangerii)和白姑鱼(Argyrosomus argentatus)声信号的时频参数(皮氏叫姑鱼发声频率在1 000~4 000 Hz之间, 峰值频率为2 000 Hz, 白姑鱼发声频率在200~800 Hz之间, 峰值频率为400 Hz)相吻合。且皮氏叫姑鱼与白姑鱼的发声存在季节性(在5~7月之间发声)与昼夜性(主要在夜间发声)(许兰英等, 1999), 均与本文结果较为一致。因此, 我们认为本研究记录到的type1声信号为皮氏叫姑鱼所发, type2声信号为白姑鱼所发。

本研究结果结合对黄海和东海东亚江豚胃容物研究结果(Lu et al, 2016; Chen et al, 2017), 我们认为东亚江豚兼具专一性捕食者与机会捕食者特征, 有两种捕食策略: 一种是被动窃听, 即在发声鱼类繁殖季节, 主要通过窃听获取食物方位, 以发声鱼类为食; 一种是主动探测, 即在非发声鱼类繁殖季节, 利用回声定位信号主动探测食物方位, 捕食易于获得的适口食物。多种鲸类已被证明依靠窃听策略捕食(Barros et al, 2004; Deecke et al, 2005; Gannon et al, 2005; Berens McCabe et al, 2010; Rodrigues et al, 2020), 这种捕食策略符合最优觅食理论(MacArthur et al, 1966)。例如在发声鱼类繁殖季节, 东亚江豚通过窃听定位能够节省主动回声定位过程中产生的能量消耗, 且能够提高捕食成功率。有研究证实, 一些鱼类能够探测到齿鲸所发出的声信号(Mann et al, 1997, 2001; Wilson et al, 2008)。此外, 鱼类声信号相比较东亚江豚的回声定位信号频率更低, 传播距离更远, 指向性更低, 东亚江豚靠窃听能够探测到更大范围内的食物(Li et al, 2007)。

3.2 保护建议本研究证明春季发声鱼类与东亚江豚具有一致的分布特征, 说明了发声鱼类资源管理在东亚江豚保护方面的重要性; 东亚江豚很可能通过被动接收鱼类声信号完成定位、捕食, 说明了水下噪声管理在东亚江豚保护方面的重要性。

渤海多数发声鱼类繁殖期也是东亚江豚繁殖、抚幼的季节(陈大刚, 1991; 王丕烈, 2012)。若发声鱼类资源量不足, 母豚将不得不消耗更多能量寻找食物, 长此以往可能导致母豚营养不足, 幼豚成活率下降, 进而影响整个种群结构的健康发展。令人担忧的是, 过去60年, 中国沿海鱼类多样性与资源量大幅降低(Zhang et al, 2020)。其中最典型的便是曾经中国四大海洋渔业种类之首的大黄鱼(Larimichthys crocea), 由于酷渔滥捕, 自然资源严重衰退, 至今野外种群没有得到恢复(Liu et al, 2008)。同样原因, 作为东亚江豚食物的两种发声鱼类带鱼(Trichiurus lepturus)与小黄鱼(Larimichthys polyactis)资源下降明显, 恐步大黄鱼后尘(Zhang et al, 2020)。发声鱼类主要为石首鱼科鱼类, 营底栖生活的特点使得底拖作业可对其造成毁灭性的影响。因此, 建议在渤海海域加大对底拖作业的监察和打击力度, 在其他海域东亚江豚分布热点区域和发声鱼类繁殖区域禁止底拖作业。

近些年海上人类活动强度持续提高, 使得海洋中本底噪声强度不断加强, 而人为噪声很大程度上与鱼类发声频段重叠, 会以听觉掩蔽的方式影响捕食者捕食(Erbe, 2008; Pine et al, 2018)。捕食者捕食效率降低, 能量消耗增加, 最终捕食者适合度受到影响(Marley, 2017)。高强度、长时间暴露于噪声环境还会给鲸类动物带来其他影响, 包括行为影响、栖息地变化, 甚至物理损伤(Nowacek et al, 2007; Weilgart, 2007)。人为噪声也会对发声鱼类造成负面影响, 例如干扰鱼类集群、栖息地改变、听觉位移、产卵终止等(Slabbekoorn et al, 2010)。

船舶噪声以频率低, 强度高为特点, 是海洋中人为噪声的主要来源(Tournadre, 2014; McWhinnie et al, 2018)。建议未来国内在规划航线时, 应避开东亚江豚分布区与鱼类繁殖区, 若无法重新规划, 应在东亚江豚分布区与鱼类繁殖区内限制船舶航行速度以降低噪声强度(Erbe et al, 2019; Joy et al, 2019; MacGillivray et al, 2019)。在国内沿海区域, 另一个无法忽视的噪声源是风电场工程建设噪声(Tougaard et al, 2020)。为了履行《巴黎协定》, 近些年国内沿海已经或将要上马大量海上风力发电项目, 建议在选址时, 充分考虑到对东亚江豚和发声鱼类的影响, 尽量避开其分布区, 或提前采取声驱赶措施, 以降低对动物的影响。

3.3 本研究可能的局限性本研究一个值得注意的问题是, 停船定点监测能否准确反映出监测点附近发声鱼类的资源分布情况。由于鱼类主要是在夜间发声(Ladich, 2015), 并且本研究的监测时段主要是从18 : 00至第二天06 : 00, 个别监测点的监测时间持续到次日中午, 因而本研究能够较为准确反映出监测点发声鱼类的资源分布情况。建议将来在该调查水域布置多个被动声学监测点, 持续开展长期的系统监测, 以更加全面、准确地掌握发声鱼类的发声规律、分布特征, 及对东亚江豚活动的影响。

4 结论本文采用被动声学监测技术, 研究了黄河口及其邻近水域春季东亚江豚种群的空间分布特征及与发声鱼类的分布关系, 并依此提出了保护建议。主要结论如下:

(1) 东亚江豚分布具有选择性, 主要集中在黄河口北部和莱州湾中部。具体而言, 88.24%的东亚江豚声学目击在黄河口北部和莱州湾中部, 其中黄河口北部东亚江豚声学目击率为0.07个/km, 莱州湾中部东亚江豚声学目击率为0.09个/km, 黄河口南部东亚江豚声学目击率为0.03个/km, 莱州湾西部东亚江豚声学目击率为0.00个/km。

(2) 发声鱼类的分布是影响东亚江豚分布的重要因素。仅在东亚江豚集中分布区黄河口北部和莱州湾中部探测到鱼类的声信号, 发声源可能为皮氏叫姑鱼和白姑鱼。

(3) 水下人为噪声与发声鱼类资源的管理是东亚江豚保护的关键, 具体建议措施为: 航道与海上风电场的选址应尽量避开东亚江豚与发声鱼类分布区, 对于无法变更的, 应在东亚江豚与发声鱼类分布区内限制船舶航行速度或提前采取声驱赶措施; 在渤海加强对底拖作业的监管和惩罚力度, 在黄海与东海东亚江豚与发声鱼类分布区内禁止底拖作业。

王丕烈, 2012. 中国鲸类. 北京: 化学工业出版社, 373-375

|

许兰英, 齐孟鹗, 1999. 黄、渤海两种鱼噪声谱的水下观测. 海洋科学, 23(4): 13-14 DOI:10.3969/j.issn.1000-3096.1999.04.006 |

陈大刚, 1991. 黄渤海渔业生态学. 北京: 海洋出版社, 273-296

|

AKAMATSU T, WANG D, WANG K, et al, 2008. Estimation of the detection probability for Yangtze finless porpoises (Neophocaena phocaenoides asiaeorientalis) with a passive acoustic method. The Journal of the Acoustical Society of America, 123(6): 4403-4411 DOI:10.1121/1.2912449 |

AKAMATSU T, WANG D, WANG K X, et al, 2002. Diving behaviour of freshwater finless porpoises (Neophocaena phocaenoides) in an oxbow of the Yangtze River, China. ICES Journal of Marine Science, 59(2): 438-443 DOI:10.1006/jmsc.2001.1159 |

BARLOW J, CHEESEMAN T, TRICKEY J S, 2021. Acoustic detections of beaked whales, narrow-band high-frequency pulses and other odontocete cetaceans in the Southern Ocean using an autonomous towed hydrophone recorder. Deep Sea Research Part Ⅱ: Topical Studies in Oceanography, 193: 104973 DOI:10.1016/j.dsr2.2021.104973 |

BARROS N B, JEFFERSON T A, PARSONS E C M, 2004. Feeding habits of Indo-Pacific humpback dolphins (Sousa chinensis) stranded in Hong Kong. Aquatic Mammals, 30(1): 179-188 DOI:10.1578/AM.30.1.2004.179 |

BENOIT-BIRD K J, AU W W L, 2003. Prey dynamics affect foraging by a pelagic predator (Stenella longirostris) over a range of spatial and temporal scales. Behavioral Ecology and Sociobiology, 53(6): 364-373 DOI:10.1007/s00265-003-0585-4 |

BERENS MCCABE E J, GANNON D P, BARROS N B, et al, 2010. Prey selection by resident common bottlenose dolphins (tursiops truncatus) in Sarasota Bay, Florida. Marine Biology, 157(5): 931-942 DOI:10.1007/s00227-009-1371-2 |

CHEN B Y, WANG L, WANG H, et al, 2017. Finless porpoises (Neophocaena asiaeorientalis) in the East China Sea: insights into feeding habits using morphological, molecular, and stable isotopic techniques. Canadian Journal of Fisheries and Aquatic Sciences, 74(10): 1628-1645 DOI:10.1139/cjfas-2016-0119 |

DAVIDSON A D, BOYER A G, KIM H, et al, 2012. Drivers and hotspots of extinction risk in marine mammals. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 109(9): 3395-3400 DOI:10.1073/pnas.1121469109 |

DEECKE V B, FORD J K B, SLATER P J B, 2005. The vocal behaviour of mammal-eating killer whales: communicating with costly calls. Animal Behaviour, 69(2): 395-405 DOI:10.1016/j.anbehav.2004.04.014 |

ERBE C, 2008. Critical ratios of beluga whales (Delphinapterus leucas) and masked signal duration. The Journal of the Acoustical Society of America, 124(4): 2216-2223 DOI:10.1121/1.2970094 |

ERBE C, MARLEY S A, SCHOEMAN R P, et al, 2019. The effects of ship noise on marine mammals-a review. Frontiers in Marine Science, 6: 606 DOI:10.3389/fmars.2019.00606 |

GANNON D P, BARROS N B, NOWACEK D P, et al, 2005. Prey detection by bottlenose dolphins, Tursiops truncatus: an experimental test of the passive listening hypothesis. Animal Behaviour, 69(3): 709-720 DOI:10.1016/j.anbehav.2004.06.020 |

HASTIE G D, WILSON B, WILSON L J, et al, 2004. Functional mechanisms underlying cetacean distribution patterns: hotspots for bottlenose dolphins are linked to foraging. Marine Biology, 144(2): 397-403 DOI:10.1007/s00227-003-1195-4 |

JEFFERSON T A, WANG J Y, 2011. Revision of the taxonomy of finless porpoises (genus Neophocaena): the existence of two species. Journal of Marine Animals and Their Ecology, 4(1): 3-16 |

JOY R, TOLLIT D, WOOD J, et al, 2019. Potential benefits of vessel slowdowns on endangered southern resident killer whales. Frontiers in Marine Science, 6: 344 DOI:10.3389/fmars.2019.00344 |

LADICH F, 2015. Sound Communication in Fishes. Vienna, Austria: Springer-Verlag, 149-173

|

LI S H, AKAMATSU T, DONG L J, et al, 2010. Widespread passive acoustic detection of Yangtze finless porpoise using miniature stereo acoustic data-loggers: a review. The Journal of the Acoustical Society of America, 128(3): 1476 DOI:10.1121/1.3455829 |

LI S H, WANG D, WANG K X, et al, 2007. Echolocation click sounds from wild inshore finless porpoise (Neophocaena phocaenoides sunameri) with comparisons to the sonar of riverine N. p. asiaeorientalis. The Journal of the Acoustical Society of America, 121(6): 3938-3946 DOI:10.1121/1.2721658 |

LIU M, SADOVY DE MITCHESON Y, 2008. Profile of a fishery collapse: why mariculture failed to save the large yellow croaker. Fish and Fisheries, 9(3): 219-242 DOI:10.1111/j.1467-2979.2008.00278.x |

LOBEL P S, KAATZ I M, RICE A N, 2010. Acoustical behavior of coral reef fishes [M] // COLE K S. Reproduction and Sexuality in Marine Fishes: Patterns and Processes. California, USA: University of California Press: 307-386.

|

LU Z C, XU S Y, SONG N, et al, 2016. Analysis of the diet of finless porpoise (Neophocaena asiaeorientalis sunameri) based on prey morphological characters and DNA barcoding. Conservation Genetics Resources, 8(4): 523-531 DOI:10.1007/s12686-016-0575-2 |

MACARTHUR R H, PIANKA E R, 1966. On optimal use of a patchy environment. The American Naturalist, 100(916): 603-609 DOI:10.1086/282454 |

MACGILLIVRAY A O, LI Z Z, HANNAY D E, et al, 2019. Slowing deep-sea commercial vessels reduces underwater radiated noise. The Journal of the Acoustical Society of America, 146(1): 340-351 DOI:10.1121/1.5116140 |

MANN D A, HIGGS D M, TAVOLGA W N, et al, 2001. Ultrasound detection by clupeiform fishes. The Journal of the Acoustical Society of America, 109(6): 3048-3054 DOI:10.1121/1.1368406 |

MANN D A, LU Z M, POPPER A N, 1997. A clupeid fish can detect ultrasound. Nature, 389(6649): 341 DOI:10.1038/38636 |

MARLEY S A, 2017. Behavioural and acoustical responses of coastal dolphins to noisy environments [D]. Australia: Curtin University: 6-132.

|

MCWHINNIE L H, HALLIDAY W D, INSLEY S J, et al, 2018. Vessel traffic in the Canadian Arctic: management solutions for minimizing impacts on whales in a changing northern region. Ocean & Coastal Management, 160: 1-17 |

NOTARBARTOLO DI SCIARA G, HOYT E, REEVES R, et al, 2016. Place-based approaches to marine mammal conservation. Aquatic Conservation: Marine and Freshwater Ecosystems, 26(S2): 85-100 |

NOWACEK D P, THORNE L H, JOHNSTON D W, et al, 2007. Reponses of cetaceans to anthropogenic noise. Mammal Review, 37(2): 81-115 DOI:10.1111/j.1365-2907.2007.00104.x |

PINE M K, HANNAY D E, INSLEY S J, et al, 2018. Assessing vessel slowdown for reducing auditory masking for marine mammals and fish of the western Canadian Arctic. Marine Pollution Bulletin, 135: 290-302 DOI:10.1016/j.marpolbul.2018.07.031 |

READ A J, 2008. The looming crisis: interactions between marine mammals and fisheries. Journal of Mammalogy, 89(3): 541-548 DOI:10.1644/07-MAMM-S-315R1.1 |

RODRIGUES V L A, WEDEKIN L L, MARCONDES M C C, et al, 2020. Diet and foraging opportunism of the Guiana Dolphin (Sotalia guianensis) in the Abrolhos Bank, Brazil. Marine Mammal Science, 36(2): 436-450 DOI:10.1111/mms.12656 |

SHAN X J, JIN X S, DAI F Q, et al, 2014. Population dynamics of fish species in a marine ecosystem: a case study in the Bohai Sea, China. Marine and Coastal Fisheries, 8(1): 100-117 |

SHAN X J, SUN P F, JIN X S, et al, 2013. Long-term changes in fish assemblage structure in the Yellow River estuary ecosystem, China. Marine and Coastal Fisheries, 5(1): 65-78 DOI:10.1080/19425120.2013.768571 |

SLABBEKOORN H, BOUTON N, VAN OPZEELAND I, et al, 2010. A noisy spring: the impact of globally rising underwater sound levels on fish. Trends in Ecology & Evolution, 25(7): 419-427 |

SPITZ J, MOUROCQ E, LEAUTÉ J P, et al, 2010. Prey selection by the common dolphin: Fulfilling high energy requirements with high quality food. Journal of Experimental Marine Biology and Ecology, 390(2): 73-77 DOI:10.1016/j.jembe.2010.05.010 |

TAYLOR B L, GERRODETTE T, 1993. The uses of statistical power in conservation biology: the vaquita and northern spotted owl. Conservation Biology, 7(3): 489-500 DOI:10.1046/j.1523-1739.1993.07030489.x |

TOUGAARD J, HERMANNSEN L, MADSEN P T, 2020. How loud is the underwater noise from operating offshore wind turbines?. The Journal of the Acoustical Society of America, 148(5): 2885-2893 DOI:10.1121/10.0002453 |

TOURNADRE J, 2014. Anthropogenic pressure on the open ocean: the growth of ship traffic revealed by altimeter data analysis. Geophysical Research Letters, 41(22): 7924-7932 DOI:10.1002/2014GL061786 |

WANG Z T, AKAMATSU T, WANG K X, et al, 2014. The diel rhythms of biosonar behavior in the Yangtze finless porpoise (Neophocaena asiaeorientalis asiaeorientalis) in the port of the Yangtze River: the correlation between prey availability and boat traffic. PLoS One, 9(5): e97907 DOI:10.1371/journal.pone.0097907 |

WEILGART L S, 2007. The impacts of anthropogenic ocean noise on cetaceans and implications for management. Canadian Journal of Zoology, 85(11): 1091-1116 DOI:10.1139/Z07-101 |

WILLIAMS R, KRKOŠEK M, ASHE E, et al, 2011. Competing conservation objectives for predators and prey: estimating killer whale prey requirements for chinook salmon. PLoS One, 6(11): e26738 DOI:10.1371/journal.pone.0026738 |

WILSON M, ACOLAS M L, BÉGOUT M L, et al, 2008. Allis shad (Alosa alosa) exhibit an intensity-graded behavioral response when exposed to ultrasound. The Journal of the Acoustical Society of America, 124(4): EL243-EL247 DOI:10.1121/1.2960899 |

YANG J W, WAN X L, ZENG X Y, et al, 2019. A preliminary study on diet of the Yangtze finless porpoise using next-generation sequencing techniques. Marine Mammal Science, 35(4): 1579-1586 DOI:10.1111/mms.12585 |

ZHANG W B, LIU M, MITCHESON Y S D, et al, 2020. Fishing for feed in China: facts, impacts and implications. Fish and Fisheries, 21(1): 47-62 DOI:10.1111/faf.12414 |

2022, Vol. 53

2022, Vol. 53