文章信息

- 辛孝科, 张立斌, 于正林, 杨红生. 2018.

- XIN Xiao-ke, ZHANG Li-bin, YU Zheng-lin, YANG Hong-sheng. 2018.

- 栖息地分布与种内竞争对刺参集群特征的影响

- Effects of habitat distribution and intraspecific competition on aggregation features of sea cucumber Apostichopus japonicus

- 海洋科学, 42(5): 138-144

- Marine Sciences, 42(5): 138-144.

- http://dx.doi.org/10.11759//hykx20180309001

-

文章历史

- 收稿日期:2018-03-09

- 修回日期:2018-04-22

2. 青岛海洋科学与技术国家实验室 海洋生态与环境科学功能实验室, 山东 青岛 266071;

3. 中国科学院大学, 北京 100049;

4. 中国科学院海洋大科学研究中心, 山东 青岛 266071

2. Laboratory for Marine Ecology and Environmental Science, Qingdao National Laboratory for Marine Science and Technology, Qingdao 266071, China;

3. University of Chinese Academy of Sciences, Beijing 100049, China;

4. Center for Ocean Mega-Science, Chinese Academy of Sciences, Qingdao 266071, China

仿刺参(Apostichopus japonicus), 又称刺参, 喜栖息于食物资源丰富的海藻床、礁岩环境, 多分布于中国北部、韩国、日本和俄罗斯东部[1, 2]。刺参具有极高营养、药用价值和经济价值[3], 当前刺参的主要养殖方式包括:池塘养殖、围堰养殖、浅海底播养殖等[4]。在众多刺参养殖模式中, 底播养殖的刺参具有病害少、风险低、生长快、品质佳等优点[5, 6]。但底播养殖还有许多亟待解决的问题, 如增殖区刺参不知去向、回捕率低、捕获方式风险高等。动物集群行为会直接或间接影响其分布[7], 研究刺参集群行为特征对于了解刺参的野外分布和增养殖资源持续利用具有重要意义。

集群是动物常见的行为特征, 动物能从集群行为中获得较高的生存收益。研究发现动物集群行为能有效交换信息并更快追踪食物, 充分利用食物资源[8, 9]。例如动物发现捕食对象后会通过声音信号向种内同伴发送食物位置[10]。集群也有利于动物减少被捕食风险, 有研究发现动物集群后警觉性明显上升, 更容易发现捕食者, 集群条件下死亡率显著下降[11], 动物更易选择合适的栖息地[12], 求偶机遇会显著上升, 有利于种群繁衍[13]。

目前国内外关于水生动物的集群行为研究较多, 如鱼类碰到同伴时, 会自发相互靠近, 聚集成不同规模群体[14], 虾类聚集成群体后会有规律的运动[15, 16]。关于棘皮动物集群研究也较为丰富, 如食物会影响绿球海胆(Strongylocentrotus droebachiensis)在野外的聚集分布[17-19]。不同动物会有不同集群规模, 如黄昏雀(Coccothraustes vespertinus)聚集规模为3~10只[20], 斑鸫鹛(Turdoides bicolor)集群数量为2~11只[21], 棘皮动物中海胆密度会因季节变化而改变[22], 海星(Protoreaster nodosus)分布受栖息地环境影响较大[23]等。关于海参群体聚集情况研究多集中在环境因子对刺参资源分布的影响, 如不同规格海参群体会分布在不同栖息地环境, 同时月相变化时其密度也会周期性改变[24], 在不同生境中海参群体密度也不相同, 其密度变化受底质[25-27]和盐度[28]等影响, 刺参群体密度也会因季节改变而发生周期性变化, 如海州湾刺参密度为(0.4~1.33)头/m2[25]。而关于刺参种内生物关系对刺参集群行为特征研究还未见报道。作者采用缩时摄影技术, 在室内环境条件下, 探究刺参集群特征以及不同密度下刺参群体分布特征, 以期揭示刺参集群行为规律, 为野外刺参增养殖与资源持续利用提供理论参考。

1 材料与方法 1.1 材料来源与暂养2017年10月于山东省荣成市天鹅湖(37°21′34″~ 37°21′35″N, 122°35′14″~122°35′15″E)采集实验所用刺参, 并在室内养殖池暂养两周, 刺参活动正常且摄食后开始实验。暂养水体持续充气, 保证溶氧在7 mg/L以上。每日换1次水, 水温为14~16℃、盐度30~32、pH 7.8~8.2。每日投喂1次饲料并清理残饵和粪便。暂养结束后随机挑选体质健壮、规格相近(100 g±20 g)个体进行实验。

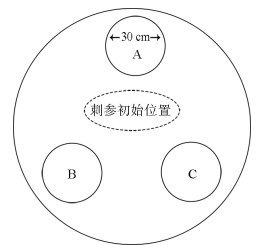

1.2 实验设计 1.2.1 栖息地对刺参分布影响将直径为30 cm的礁石放置于直径为1.3 m圆形水缸中(A、B和C其中1处, 图 1), 缸内水深约30 cm, 以模拟刺参野外生存环境中的栖息地。将缩时摄影机(Brinno TLC-200)架设于水缸上方, 摄影机拍摄间隔为每5 s拍摄1帧(1帧/5 s), 分辨率1280×720, 拍摄视频质量设置为最佳。LED光源设置在水缸两侧以减少光源直射而影响视频分析效果。实验时将单头刺参放置在水缸中央, 持续拍摄24 h。实验过程中暂停投喂, 溶氧、水温、盐度和pH始终保持在正常范围。

|

| 图 1 刺参栖息地位置图 Fig. 1 Aquarium design used in sea cucumber preference experiments A、B和C为实验中栖息地放置位置 A, B and C indicate the position of three habitat patches placed equidistantly around tank |

将三堆直径为30 cm的礁石放置在水缸A、B和C处, 实验时刺参放置在水缸中央, 持续拍摄24 h。实验设计6个处理, 密度梯度为1、3、5、10、15头/缸(0.75、2.26、3.77、7.53、11.31头/m2), 分别记为D1、D3、D5、D10和D15。每个处理设置3次重复且每次重复都更换实验对象, 每次实验前清洗实验缸并全部换水, 以减少残余粪便的影响。实验过程中暂停投喂, 溶氧含量、水温、盐度和pH始终保持在正常范围。

将视频数据按0.5倍播放速度播放, 待刺参开始运动后记为有效运动, 根据刺参在实验缸内实际分布位置, 肉眼记录每只刺参全程运动位置来统计刺参在不同位置的栖息时间等基础数据进行分析。

1.3 数据计算与分析平均聚集率(mean attractive rate, MAR)是指平均每个统计周期某固定时间点刺参聚集在分布位置上的数量之和与实验总观察对象个数比值, 可作为评估刺参对栖息环境选择性指标。计算公式为

式中, Ni为第i(i=1, 2, …, n)次聚集在栖息地上的刺参数量; N为该组实验刺参总数量(头); n为1个实验周期内记录次数。

平均聚集时间比例(mean attractive time, MAT)是指平均每个统计周期内每个刺参在栖息地聚集时间与总时间比值的平均值。计算公式为

式中, Ti为第i(i=1, 2, …, n)头刺参聚集在栖息地时间; T为第i(i=1, 2, …, n)头刺参运动总时间; n为刺参数量。

在本实验中, 平均聚集率实验周期设置为每隔2 h统计1次刺参栖息位置, 实验总周期为24 h; 平均聚集时间周期设置为24 h。

1.4 统计分析数据以平均值±标准差(mean ± SD)表示, 实验数据采用SPSS19统计软件进行分析。刺参聚集位置差异采用独立样本T检验(Independent T-test)进行分析。刺参集群特征采用卡方检验(Pearson Chisquared tests of independence)进行分析, 在刺参集群特征分析实验中, 刺参随机分布有10种理论可能性结果, 其中包括: 3只刺参占据同一栖息地概率为0.3, 其中2只刺参占据同一栖息地而另外1只刺参占据剩余任意两处栖息地概率为0.6, 3只刺参分别占据3处栖息地概率为0.1, 若刺参集中分布在同一栖息地则认为刺参有明显集群倾向, 若分布在不同栖息地中则认为不具有集群倾向。不同密度下刺参聚集差异采用单因素方差分析(one-way ANOVA)进行分析。P < 0.05作为差异显著水平, P < 0.01作为差异极显著水平。

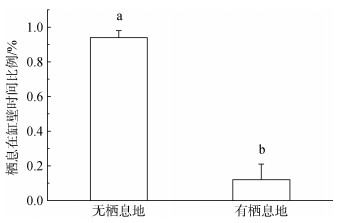

2 结果与分析 2.1 栖息地分布对刺参集群特征的影响统计分析表明栖息地对刺参分布有极显著影响(P < 0.01)。在无栖息地条件下, 刺参被放置在实验缸中心后在1 h内全部运动至实验缸缸壁处。刺参在到达缸壁后会环绕缸壁持续或间歇性运动。而在栖息地存在情况下刺参分布位置时间比例如图 2所示, 刺参明显聚集在栖息地处, 聚集在栖息地时间与总聚集时间比值(0.88±0.11)显著高于在缸壁处的比值(P < 0.05), 可见刺参对栖息地有明显偏好性。

|

| 图 2 不同位置栖息时间比例 Fig. 2 Proportion of time in different habitats 数据柱标注相同字母表示无显著差异, 不同字母表示有显著差异(P < 0.05), 图 4和图 5同 Value columns with same-letter superscripts indicate no significant difference; columns with different-letter superscripts indicate significant difference (P < 0.05), the same as Fig. 4 and Fig. 5 |

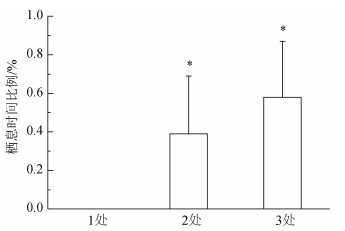

刺参分布位置统计如图 3所示, 未发现刺参集中分布在同一栖息地情况, 刺参聚集在2处栖息地概率为0.4, 聚集3处栖息地概率为0.6, 这一比值(0︰0.4︰0.6)与理论值(0.3︰0.6︰0.1)差异显著(P < 0.05), 表明刺参更倾向于呈斑块状分布。

|

| 图 3 刺参占据栖息地数目 Fig. 3 Number of patches occupied by 3 sea cucumbers (degree of dispersion) *表示结果与理论值有差异显著水平, P < 0.05 The binomial probability was significant where indicated by * P < 0.05 between result and expectation |

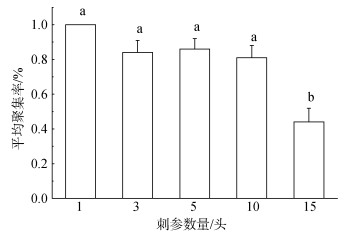

24 h周期内不同密度刺参平均聚集率如图 4所示, 可见D1、D3、D5、D10情况下, 刺参的聚集率分别为1、0.84、0.86、0.81, 呈现出下降趋势, 但各密度之间没有显著差异(P > 0.05)。当刺参密度达到15头/缸时, 种内竞争压力加剧, 刺参平均聚集率显著下降至0.44(P < 0.05)。

|

| 图 4 不同密度仿刺参平均聚集率比较 Fig. 4 Comparison of MAR at different density |

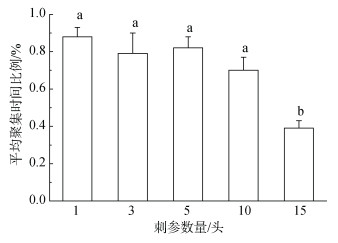

24 h周期内不同密度刺参平均聚集时间比例如图 5所示, 可见刺参在D1、D3、D5、D10栖息地分布时间分别为0.88、0.79、0.81、0.70, 呈现出下降趋势, 但各密度之间没有显著差异(P > 0.05)。当刺参密度达到15头/缸时, 刺参平均聚集时间显著下降至0.39(P < 0.05)。其中在D10时, 有2头刺参未聚集在栖息地中, 会不停或间歇环绕缸壁和沿缸底穿梭运动, 而在D15时, 平均超过8头刺参会不停运动, 在运动过程中遇到栖息地后也会迅速离开。

|

| 图 5 不同密度仿刺参平均聚集时间比较 Fig. 5 Comparison of MAT at different density |

野外调查发现刺参多聚集在饵料资源丰富的海藻床及礁石等栖息地[25]。栖息地不仅可以为刺参提供遮蔽环境, 且所聚集的底栖生物和其他微型生物还可以作为刺参的食物来源[29]。在本实验中, 相对于缸底等空旷区域, 刺参更喜栖息在能提供遮蔽环境的礁石处, 表明刺参的集群特征研究必须以栖息地为基础来分析[30]。此外实验发现刺参在运动时并没有集中分布在同一栖息地, 而是显著分散栖息在2处或3处栖息地, 表明刺参在分布时呈现出斑块分布特征。相似结果在其他棘皮动物中也有所发现, 如研究发现海胆在运动时方向会呈现出随机性, 且相邻两步运动方向之间没有相关性[31]。在野外实验中, 通过对海胆体外标记发现, 海胆并未集结成群搜寻食物和栖息地, 而是以被释放点为中心向四周辐散运动[32]。相对于种内同伴吸引, 环境因素更易对刺参在自然生境内的分布造成显著影响。有研究表明刺参密度会随季节呈周期性变化, 这可能是由温度影响引起的季节性分布差异[33]。糙海参(Holothuria scabr)野外分布受聚集礁石深度及底质类型影响, 并且其聚集明显受到月相变化影响, 在月满约一周后聚集密度达到最大, 然后逐渐降低[24]。

相对于独居生活, 集群有利于增加动物捕食机率、抵抗捕食者、减少能量消耗及获得更高的交配机遇, 生物会在集群成本和收益的平衡中做出选择以获得最大的生态收益[34]。刺参主要食物来源是底泥中的碎屑有机物、底栖微藻和其他微型生物, 食物获取方式简单[5]。以往研究发现, 在食物资源充足条件下阿拉斯加红参(Parastichopus californicus)运动随机性变高, 原因为随机运动有利于搜寻食物资源并可以更多时间摄取食物[35]。刺参在幼体阶段容易被天敌捕食, 而达到成体阶段后被捕食率显著降低[26, 36], 因此成年刺参集群在抵抗捕食者过程中收益并不高。动物在集群生活时社会分工明确, 这有利于降低新陈代谢率, 减少生命活动能量消耗, 缓解个体独自活动压力[37]。刺参在实验室内单独饲养和集中饲养时, 集中饲养刺参能量消耗较高[38]。集群行为会增大动物与同伴相遇机率, 提高繁殖效率。例如有研究发现海星(Asterias vulgaris)、海蛇尾(Ophiopholis aculeata)以及海胆等棘皮动物在配子排放期会出现明显集群现象[39, 40], 动物将配子释放到海水中进行体外受精, 因此集群行为能有效提高动物繁殖成功率。非生物因素对于海参繁殖影响显著。温度对海参配子发育与产卵行为也有重要调控作用[41-43], 温度升高后海参将配子释放到周围海水中来进行繁殖[43, 44], 同时月圆对于刺参产卵行为也有重要影响[45]。综上, 在非繁殖期成年刺参集群生态收益并不高, 而且其生长发育还会因密度增大而受到影响。

研究发现密度对刺参生理与行为状态具有重要影响[46, 47]。密度过大时刺参群体内会出现明显生长压制现象。在规格不同条件下, 大规格刺参会压制小规格刺参生长, 小规格个体生长速度非常缓慢。初始规格相同的条件下, 无论食物资源是否充足, 随着密度增大, 刺参能量消耗升高, 平均生长率下降。在饲养一段时间后刺参个体之间生长差异明显[46, 47]。在本实验中, D10条件下会有少量刺参并未聚集在栖息地内, 而是围绕缸壁持续或间歇性运动, 以远离实验观察区。在D15条件下这一数量明显增加, 超过半数刺参在观察区内围绕缸壁或穿梭于缸底持续性运动, 刺参平均聚集率和平均聚集时间比例显著下降。根据视频分析发现, 刺参在运动过程中遇到栖息地时也迅速离开并继续运动, 并未长时间停留在栖息地上, 说明种内竞争已经明显影响刺参运动行为。野外调查中, 刺参密度通常为(0.1~0.5)头/m2, 显著低于人工养殖密度, 这可能是因为在密度过高, 种内竞争压力大时, 刺参远离其他个体以缓解种内竞争压力, 导致密度下降[48, 49]。

在实验室条件下刺参短期内多呈现相对离散的斑块状分布, 野外条件下刺参的资源分布特征及其环境适应性亟待深入研究和揭示, 为了解刺参的种群的繁衍机制和制定刺参资源保护策略奠定基础。

| [1] |

Hamel J F, Mercier A. Population status, fisheries and trade of sea cucumbers in temperate areas of the Northern Hemisphere[J]. Fao Fisheries & Aquaculture Technical Paper, 2008, 516: 257-291. |

| [2] |

Chang Y, Sui X, Li J. The current situation, problem and prospect on the Apostichopus japonicus aquaculture[J]. Fisheries Science, 2006, 25(4): 198-201. |

| [3] |

廖玉麟. 中国动物志:棘皮动物门海参纲[M]. 北京: 科学出版社, 1997: 148-149. Liao Yulin. Fauna Sinica, Phylum echinodermata, class holothuroidea[M]. Beijing: Science Press, 1997: 148-149. |

| [4] |

林承刚, 汝少国, 杨红生, 等. 刺参对人工礁体设计关键指标的选择性[J]. 海洋科学, 2012, 36(3): 13-21. Lin Chenggang, Ru Shaoguo, Yang Hongsheng, et al. Selectivity of sea cucumber (Apostichopus japonicus, Selenka) for key indicators in artificial reef structure design[J]. Marine Sciences, 2012, 36(3): 13-21. |

| [5] |

杨红生, 周毅, 张涛. 刺参生物学:理论与实践[M]. 北京: 科学出版社, 2014: 276-277. Yang Hongsheng, Zhou Yi, Zhang Tao. The biology of the cucumbers-theory and practice[M]. Beijing: Science Press, 2014: 276-277. |

| [6] |

杨东, 周政权, 张建设, 等. 烟台牟平海洋牧场夏季大型底栖动物群落特征[J]. 海洋科学, 2017, 41(5): 134-143. Yang Dong, Zhou Zhengquan, Zhang Jianshe, et al. Characteristics of macrobenthic communities at the Muping marine ranch of Yantai in summer[J]. Marine Sciences, 2017, 41(5): 134-143. |

| [7] |

Palmer M A, Allan J D, Butman C A. Dispersal as a regional process affecting the local dynamics of marine and stream benthic invertebrates[J]. Trends in Ecology & Evolution, 1996, 11(8): 322. |

| [8] |

Pitcher T J, Magurran A E. Fish in larger shoals find food faster[J]. Behavioral Ecology & Sociobiology, 1982, 10(2): 149-151. |

| [9] |

Krause J, Ruxton G D. Living in groups[M]. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2002.

|

| [10] |

Brown C R, Brown M B, Shaffer M L. Food-sharing signals among socially foraging cliff swallows[J]. Anim Behav, 1991, 42(4): 551-564. DOI:10.1016/S0003-3472(05)80239-8 |

| [11] |

Watson M, Aebischer N J, Cresswell W. Vigilance and fitness in grey partridges Perdix perdix:the effects of group size and foraging-vigilance trade-offs on predation mortality[J]. Journal of Animal Ecology, 2007, 76(2): 211-221. DOI:10.1111/jae.2007.76.issue-2 |

| [12] |

Fortin D, Fortin M E, Beyer H L, et al. Group-size-mediated habitat selection and group fusion-fission dynamics of bison under predation risk[J]. Ecology, 2009, 90(9): 2480-2490. DOI:10.1890/08-0345.1 |

| [13] |

Hattori A. Inter-group movement and mate acquisition tactics of the protandrous anemonefish, Amphiprion clarkii, on a coral reef, Okinawa[J]. Jpn J Ichthyol, 1994, 41: 159-165. |

| [14] |

Eriksson A, Jacobi M N, Nystrom J, et al. Determining interaction rules in animal swarms[J]. Behavioral Ecology, 2012, 21(5): 1106-1111. |

| [15] |

Strand S W, Hamner W M. Schooling behavior of Antarctic krill (Euphausia superba) in laboratory aquaria:Reactions to chemical and visual stimuli[J]. Mar Biol, 1990, 106(3): 355-359. DOI:10.1007/BF01344312 |

| [16] |

Kawaguchi S, King R, Meijers R, et al. An experimental aquarium for observing the schooling behaviour of Antarctic krill (Euphausia superba)[J]. Deep Sea Research Part Ⅱ:Topical Studies in Oceanography, 2010, 57(7-8): 683-692. DOI:10.1016/j.dsr2.2009.10.017 |

| [17] |

Garnick E. Behavioral ecology of Strongylocentrotus droebachiensis(Muller)(Echinodermata:Echinoidea)[J]. Oecologia, 1978, 37(1): 77-84. DOI:10.1007/BF00349993 |

| [18] |

Vadas R, Elner R, Garwood P, et al. Experimental evaluation of aggregation behavior in the sea urchin Strongylocentrotus droebachiensis[J]. Mar Biol, 1986, 90(3): 433-448. DOI:10.1007/BF00428567 |

| [19] |

Lauzon-Guay J S, Scheibling R E. Behaviour of sea urchin Strongylocentrotus droebachiensis grazing fronts:Food-mediated aggregation and density-dependent facilitation[J]. Marine Ecology Progress, 2007, 329(12): 191-204. |

| [20] |

Bekoff M. Vigilance, flock size, and flock geometry:information gathering by western evening grosbeaks (Aves, Fringillidae)[J]. Ethology, 1995, 99(1-2): 150-161. |

| [21] |

Radford A N, Ridley A R. Individuals in foraging groups may use vocal cues when assessing their need for anti-predator vigilance[J]. Biology Letters, 2007, 3(3): 249-252. DOI:10.1098/rsbl.2007.0110 |

| [22] |

Lauzon-Guay J S, Scheibling R E. Seasonal variation in movement, aggregation and destructive grazing of the green sea urchin (Strongylocentrotus droebachiensis) in relation to wave action and sea temperature[J]. Mar Biol, 2007, 151(6): 2109-2118. DOI:10.1007/s00227-007-0668-2 |

| [23] |

Bos A R, Gumanao G S, Alipoyo J C E, et al. Population dynamics, reproduction and growth of the Indo-Pacific horned sea star, Protoreaster nodosus(Echinodermata; Asteroidea)[J]. Mar Biol, 2008, 156(1): 55-63. DOI:10.1007/s00227-008-1064-2 |

| [24] |

Mercier A, Battaglene S C, Hamel J F. Periodic movement, recruitment and size-related distribution of the sea cucumber Holothuria scabra in Solomon Islands[J]. Hydrobiologia, 2000, 440(1-3): 81-100. |

| [25] |

张宏晔, 许强, 刘辉, 等. 海州湾前三岛海域底播刺参群体特征初探[J]. 海洋科学, 2015, 39(6): 1-7. Zhang Hongye, Xu Qiang, Liu Hui, et al. Preliminary study on the property of bottom mariculture sea cucumber, group in Qiansan Islands, Haizhou Bay[J]. Marine Science, 2015, 39(6): 1-7. |

| [26] |

So J J, Hamel J F, Mercier A. Habitat utilisation, growth and predation of Cucumaria frondosa:implications for an emerging sea cucumber fishery[J]. Fisheries Management and Ecology, 2010, 17(6): 473-484. DOI:10.1111/fme.2010.17.issue-6 |

| [27] |

Slater M J, Jeffs A G. Do benthic sediment characteristics explain the distribution of juveniles of the deposit-feeding sea cucumber Australostichopus mollis?[J]. Journal of Sea Research, 2010, 64(3): 241-249. DOI:10.1016/j.seares.2010.03.005 |

| [28] |

侯西坦, 廖梅杰, 李彬, 等. 刺参4个不同选育品系幼参对低盐胁迫的耐受及生理生化响应[J]. 海洋科学, 2016, 40(5): 19-28. Hou Xitan, Liao Meijie, Li Bin, et al. Response to low salinity of four strains of sea cucumber Apostichopus japonicus larvae[J]. Marine Sciences, 2016, 40(5): 19-28. |

| [29] |

秦传新, 董双林, 牛宇峰, 等. 不同类型附着基对刺参生长和存活的影响[J]. 中国海洋大学学报(自然科学版), 2009, 39(3): 392-396. Qin Chuanxin, Dong Shuanglin, Niu Yufeng, et al. Effects of shelter type on the growth and survival rate of sea cucumber, Apostichopus japonicus Selenka, in earthen pond[J]. Periodical of Ocean University of China, 2009, 39(3): 392-396. |

| [30] |

吴艳庆, 赵奎峰, 刘立明, 等. 池塘网箱投放不同附着基对附着生物演替及刺参保苗效果的影响[J]. 海洋科学, 2016, 40(4): 22-31. Wu Yanqing, Zhao Kuifeng, Liu Liming, et al. Effects of substrate type on succession of periphyton and intermediate seedling culture of sea cucumber, Apostichopus japonius Selenka, in net cages set in an earthen pond[J]. Marine Sciences, 2016, 40(4): 22-31. |

| [31] |

Dumont C P, Himmelman J H, Robinson S M C. Random movement pattern of the sea urchin Strongylocentrotus droebachiensis[J]. Journal of Experimental Marine Biology & Ecology, 2007, 340(1): 80-89. |

| [32] |

Dumont C, Himmelman J H, Russell M P. Size-specific movement of green sea urchins Strongylocentrotus droebachiensis on urchin barrens in eastern Canada[J]. Marine Ecology Progress, 2004, 276(1): 93-101. |

| [33] |

Yamana Y, Hamano T, Goshima S. Seasonal distribution pattern of adult sea cucumber Apostichopus japonicus(Stichopodidae) in Yoshimi Bay, western Yamaguchi Prefecture, Japan[J]. Fisheries Science, 2009, 75(3): 585-591. DOI:10.1007/s12562-009-0076-2 |

| [34] |

Aureli F, Cords M, Schaik C P V. Conflict resolution following aggression in gregarious animals:a predictive framework[J]. Anim Behav, 2002, 64(3): 325-343. DOI:10.1006/anbe.2002.3071 |

| [35] |

van Dam-Bates P, Curtis D L, Cowen L L, et al. Assessing movement of the California sea cucumber Parastichopus californicus in response to organically enriched areas typical of aquaculture sites[J]. Aquaculture Environment Interactions, 2016, 8: 67-76. DOI:10.3354/aei00156 |

| [36] |

Hatanaka H, Uwaoku H, Yasuda T. Experimental studies on the predation of juvenile sea cucumber, Stichopus japonicus by sea star, Asterina pectinifera[J]. Aquaculture Science, 1994, 42(4): 563-566. |

| [37] |

Hennessy M B, Kaiser S, Sachser N. Social buffering of the stress response:Diversity, mechanisms, and functions[J]. Front Neuroendocrin, 2009, 30(4): 470-482. DOI:10.1016/j.yfrne.2009.06.001 |

| [38] |

Liang M, Dong S L. Individual variation in growth in sea cucumber Apostichopus japonicus(Selenck) housed individually[J]. Journal of Ocean University of China, 2010, 9(3): 291-296. DOI:10.1007/s11802-010-1739-4 |

| [39] |

Himmelman J, Dumont C, Gaymer C, et al. Spawning synchrony and aggregative behaviour of cold-water echinoderms during multi-species mass spawnings[J]. Marine Ecology Progress, 2008, 361(1): 161-168. |

| [40] |

Ru X S, Zhang L B, Liu S L, et al. Energy budget adjustment of sea cucumber Apostichopus japonicus during breeding period[J]. Aquaculture Research, 2018, 49(4): 1657-1663. DOI:10.1111/are.2018.49.issue-4 |

| [41] |

Ru X S, Zhang L B, Liu S L, et al. Reproduction affects locomotor behaviour and muscle physiology in the sea cucumber, Apostichopus japonicus[J]. Anim Behav, 2017, 133: 223-228. DOI:10.1016/j.anbehav.2017.09.024 |

| [42] |

Battaglene S C, Seymour J E, Ramofafia C, et al. Spawning induction of three tropical sea cucumbers, Holothuria scabra, H.fuscogilva and Actinopyga mauritiana[J]. Aquaculture, 2002, 207(1–2): 29-47. |

| [43] |

Morgan A D. Induction of spawning in the sea cucumber Holothuria scabra(Echinodermata:Holothuroidea)[J]. Journal of the World Aquaculture Society, 2000, 31(2): 186-194. DOI:10.1111/jwas.2000.31.issue-2 |

| [44] |

杨学明, 吴明灿, 张立, 等. 糙海参精子的发生及超微形态结构[J]. 海洋科学, 2016, 40(5): 49-56. Yang Xueming, Wu Mingcan, Zhang Li, et al. Spermatogenesis and sperm morphology of sea cucumber, Holothuria scabra[J]. Marine Sciences, 2016, 40(5): 49-56. |

| [45] |

Morgan A D. Spawning of the temperate sea cucumber, Australostichopus mollis(Levin)[J]. Journal of the World Aquaculture Society, 2009, 40(3): 363-373. DOI:10.1111/jwas.2009.40.issue-3 |

| [46] |

Dong S L, Liang M, Gao Q, et al. Intra-specific effects of sea cucumber (Apostichopus japonicus) with reference to stocking density and body size[J]. Aquaculture Research, 2010, 41(8): 1170-1178. |

| [47] |

裴素蕊, 董双林, 王芳, 等. 限定食物资源下密度对刺参个体生长的影响[J]. 中国海洋大学学报(自然科学版), 2013, 43(3): 32-37. Pei Surui, Dong Shuanglin, Wang Fang, et al. Effects of sea cucumber (Apostichopus japonicus) density on its growth under limited feed supply[J]. Periodical of Ocean University of China, 2013, 43(3): 32-37. |

| [48] |

Gavrilova G, Sukhin I Y. Characteristics of the Japanese sea cucumber Apostichopus japonicus's population in the Sea of Japan (Kievka Bay)[J]. Oceanology, 2011, 51(3): 449-456. DOI:10.1134/S0001437011030076 |

| [49] |

Lysenko V, Zharikov V, Lebedev A. The abundance and distribution of the Japanese sea cucumber, Apostichopus japonicus(Selenka, 1867)(Echinodermata:Stichopodidae), in nearshore waters of the southern part of the Far Eastern State Marine Reserve[J]. Russian Journal of Marine Biology, 2015, 41(2): 140-144. DOI:10.1134/S1063074015020078 |

2018, Vol. 42

2018, Vol. 42